The third chapter in the multi-part auction series of the Estate of Sir Mangaldas Nathubhai turns to the shelves of his Girgaum and Malabar Hill homes — the quiet centre of a cultivated Bombay life. Known to the city as a philanthropist and reformer, Sir Mangaldas was also a deliberate collector — one who read about what he acquired. His library was a place of study as much as of leisure: Hamlet beside The Grammar of Ornament, scripture beside travelogues, manuals of craft beside memoirs of empire.

While Gujarati was the language spoken at home, the family’s mastery of English was remarkable. Across generations, they read widely and well — from scripture and Shakespeare to travelogues, histories, and manuals of art and design. Sir Mangaldas’s grandson Kishoredas Nathubhai, his wife Kusumben, and Kishoredas’s sister Kamlavati — among the earliest women graduates of the University of Bombay — all carried forward this intellectual legacy, ensuring that the Mangaldas Library remained a living record of study, curiosity, and cultivated life.

Faith and Reflection

The Holy Bible, King James Version, circa 1860

A Victorian King James Bible, printed for the Queen’s Majesty, rests beside The Life of Man Symbolised (1866), inscribed “From Herbert Giraud to Mangaldas Nathoobhoy Esq., with kindest regards, 1873.”

The Life of Man Symbolised (1866)

Together, these volumes reveal the moral and intellectual dimensions of a life that balanced reform with introspection. The gift from Herbert Giraud, a friend and contemporary, also reflects the networks of courtesy and shared learning that surrounded Sir Mangaldas in nineteenth-century Bombay.

The Visual and Photographic India

The earliest volumes reach back to the dawn of the nineteenth century — James Forbes’s Oriental Memoirs (1813), Linney Gilbert’s India Illustrated, and J. H. Furneaux’s Glimpses of India — richly illustrated records of a world being described, drawn, and photographed for an international audience. To own them in Bombay was to engage with the expanding world beyond it, and to see the subcontinent not only as subject but as source of visual knowledge.

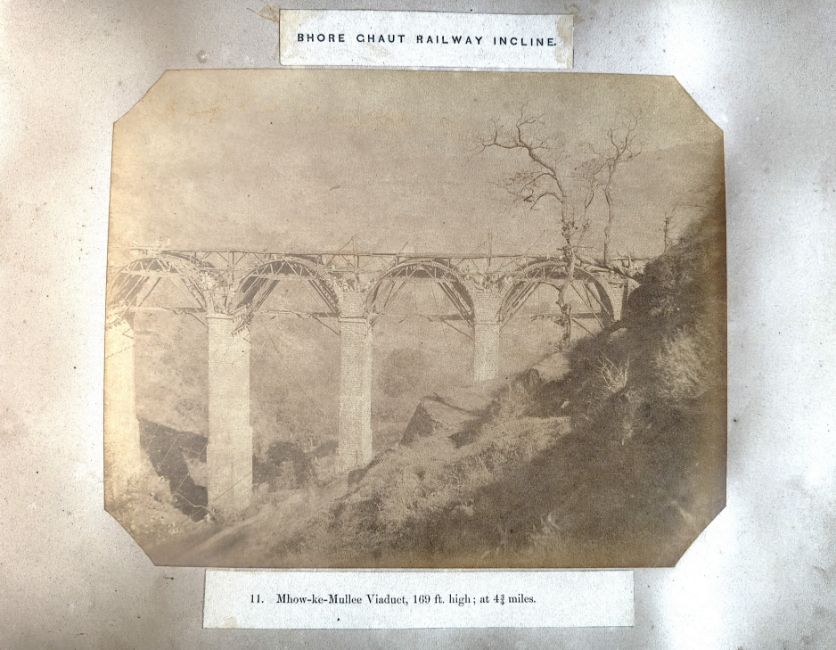

Mhow-ke-Mullee Viaduct, Bhore Ghaut Railway Incline, circa 1860.

Among the most extraordinary visual documents in the collection is an album of 43 original albumen prints attributed to Samuel Bourne and Charles Shepherd, founders of the legendary Bourne & Shepherd studio. Created circa 1860 during the construction of the Great Indian Peninsula Railway’s Bhore Ghaut Incline, the album chronicles the monumental civil engineering that connected Bombay to Poona (Pune). These photographs — depicting viaducts, rock cuttings, and the Mhow-ke-Mullee Viaduct carved through the Western Ghats — are not only triumphs of early photography but also rare primary records of India’s industrial modernity. At its peak, the project employed over 40,000 men, and albums like this are now considered among the most significant visual archives of nineteenth-century engineering in the subcontinent.

Empire, Society, and Ceremony

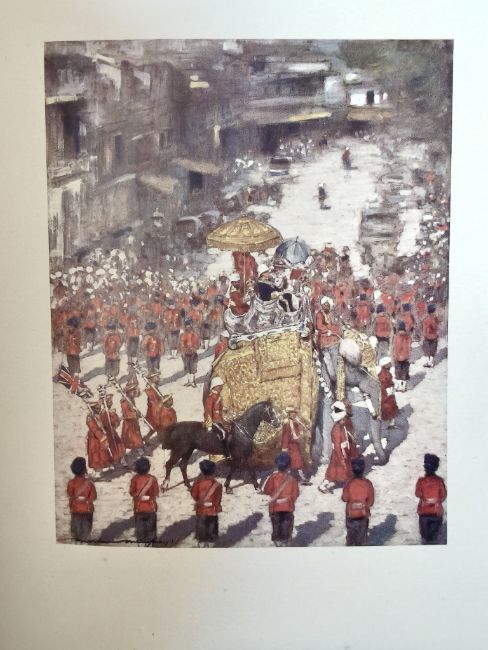

The Durbar, Mortimer Menpes, 1903

Alongside these stand the imperial chronicles: Mortimer and Dorothy Menpes’s The Durbar (1903), Sarah Tytler’s Life of Her Most Gracious Majesty the Queen, and W. W. Hunter’s The Indian Empire: Its History, People and Products — documents of power and pageantry read with curiosity and discernment. They reflect a family that engaged with empire not through imitation, but through awareness — as readers who observed the spectacle of authority from within Bombay’s own rising civic sphere.

Literature and Learning

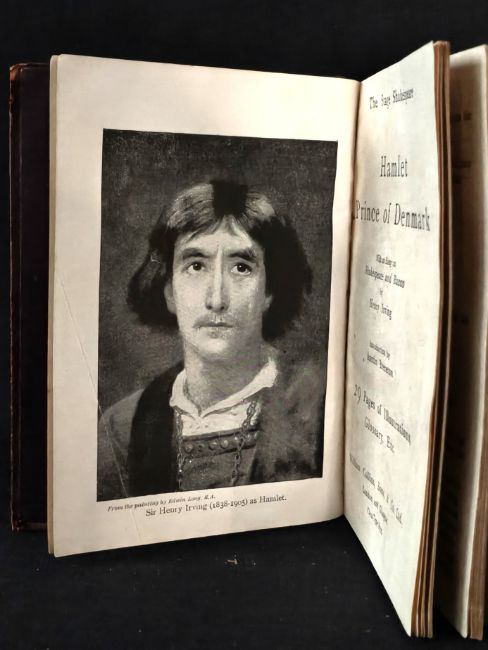

Hamlet, from The Stage Shakespeare series. Frontispiece depicting Sir Henry Irving as Hamlet

His library was also a record of wide reading. A gilt-edged edition from The Stage Shakespeare series, featuring Sir Henry Irving’s portrait as Hamlet. This compact volume reflects the family’s engagement with English literary and theatrical culture. Shakespeare’s Hamlet shared space with the orations of Cicero and Demosthenes, world essays, anthologies, and Punch’s wit — a collection that reflected both erudition and humour. These works demonstrate how the Mangaldas household, while rooted in Indian culture, was intellectually fluent in English thought and letters, bridging the literary and the lived.

Art, Design, and Connoisseurship

Equally revealing are the reference books that guided the eye of a collector — Owen Jones’s Grammar of Ornament, R. Davis Benn’s Style in Furniture, Edward Dillon’s Porcelain, and F. J. Britten’s Old Clocks and Watches and Their Makers. These manuals shaped the collections seen in earlier chapters, linking study to connoisseurship and confirming Sir Mangaldas’s reputation as a man who collected through learning — one who read before he acquired, and understood before he displayed.

Bombay Modernity

Later additions extended the library into the twentieth century. Nandalal Bose’s Rūpāvali (1939) and Ramananda Chatterjee’s Picture Albums from Santiniketan brought modern Indian art into the same lineage, while James Douglas’s Glimpses of Old Bombay and the Burmah-Shell Vintage Cars Album reflected a city in transformation — from colonial port to modern metropolis.

Among the most unexpected volumes preserved within the collection is the Cricket Legends of Colonial India: The Mangaldas Family Autograph Book — a slim, timeworn album belonging to Sir Mangaldas’s great-granddaughter, Meenal K. P. Mangaldas. Its pages, still intact after nearly a century, carry signatures and photographs of cricketing legends from the 1920s and 1930s, including C. K. Nayudu, Lala Amarnath, Mushtaq Ali, and Jack Ryder. More than a keepsake, the book reflects the family’s enduring instinct to preserve fragments of cultural history — where art, sport, and society intertwined.

Legacy

Preserved across generations, the Mangaldas Library now opens to the public for the first time. Its volumes — illustrated, inscribed, and gilt — trace a century of reading, collecting, and quiet curiosity. Together, they offer a portrait of a Bombay family that found as much wonder in books as in the porcelain, clocks, and treasures that shared their rooms.