There was a time when Amal Chandra Home Ray, known to peers as simply Amal Home, was a name familiar to Bengal’s cultural, literary, and political elite. Described by writer Nirad C. Chaudhuri as a “showman, an impresario,”[1] Amal was an elegant, erudite, complex figure whose legacy today lives on in scattered memories, faded photographs, and the quiet efforts of his daughter, Amalina Dutta, to restore him to public memory.

This essay gathers and illuminates the man behind the glamorous veneer. A man shaped by the fire of political idealism, the calm of literary devotion, and the ache of unfulfilled potential.

Family and Roots: From Sahila to Santiniketan

Amal Home was born in 1894 in what is now Bangladesh. His family, originally from Sahila village in Mymensingh (under Itna police station, Kishorganj subdivision), was steeped in learning and reformist values. His father, Gagan Chandra Home, embraced Brahmoism and broke from orthodox convention, while his uncle, Mahendra Chandra Home, father of Amal’s cousin, historian Niharranjan Ray, remained an atheist.[2] This Home–Ray lineage would go on to shape Bengali scholarship, reformist politics, and modernist thought. In this fertile, questioning environment, Amal imbibed the rationalism of the Brahmo Samaj, the discipline of colonial modernity, and a restless cosmopolitan curiosity.

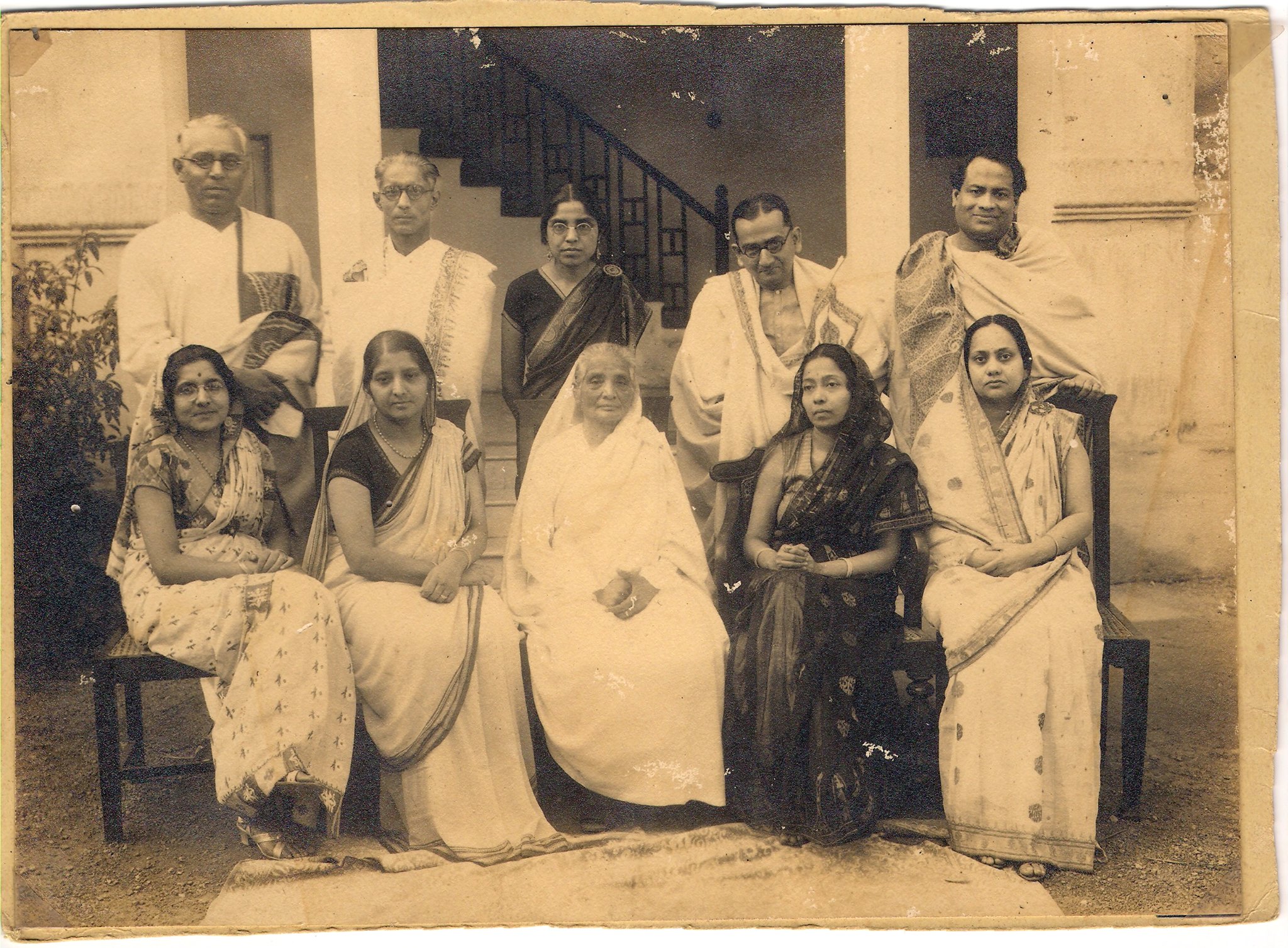

Amal Home with his in-laws, The Sarkars', Kolkata

Amal Home with his in-laws, The Sarkars', Kolkata

Picture Credits: Amal Home - Letters and His Writings.

He married Ila Sarkar, daughter of Hemlata Sarkar (a pioneering educationist) and granddaughter of the reformer Shivnath Shastri. This alliance brought him into the heart of Kolkata’s progressive Brahmo circles. Their daughter, Amalina, was named by Rabindranath Tagore himself, a portmanteau of “Amal” and “Ila.”[2]

Amal Home with wife Ila Sarkar

Picture Credits: Amal Home - Letters and His Writings.

Early Public Life and the Foundations of Print

Amal’s entry into public life came early. He later recalled attending the 1906 Indian National Congress session in Calcutta at age thirteen; a moment that ignited his lifelong engagement with cultural politics.

His literary training was shaped under Ramananda Chatterjee, the legendary editor of The Modern Review and Prabasi, who mentored him and secured his first editorial roles in Punjab. Amal went on to work with The Panjabee and later under Kalinath Roy at The Lahore Tribune, serving during the tense Martial Law period of 1919. A later issue of The Modern Review praised how he had “valiantly upheld the best traditions of our profession during the dangerous period of martial law.”

Returning to Calcutta, Amal became Editor of the Calcutta Municipal Gazette, where he produced landmark issues with lasting documentary value. These included the Tagore Birthday Supplement (May 1941), with a foreword by Hallam Tennyson, and the Independence Commemoration Number (December 1947)—both circulated widely within Santiniketan.

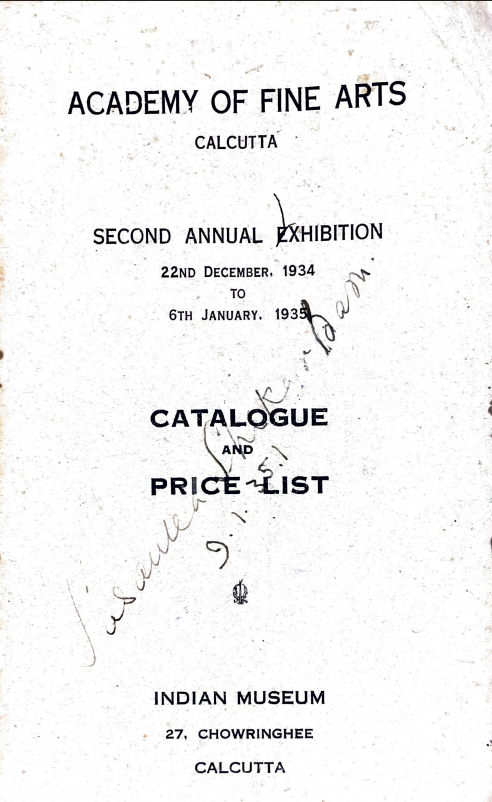

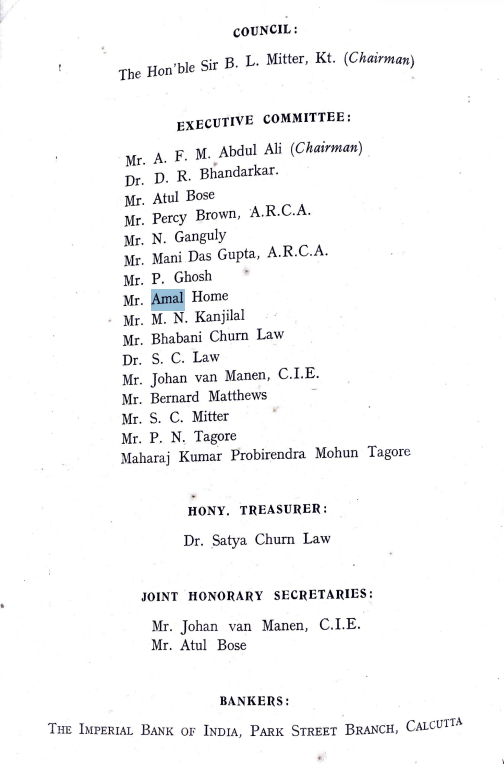

He also served on the Executive Committee of the Academy of Fine Arts, Calcutta, as recorded in the 1934–35 exhibition catalogue.[3] His name appeared alongside Percy Brown, Atul Bose, Johan van Manen, and P.N. Tagore—positioning him within Bengal’s art institutional landscape.

The Man in the Astrakhan Cap: Style as Substance

Amal Home was unmistakable in any crowd. Tall, well-built, and handsome, he was always impeccably dressed, whether in Muslim, Bengali, or European clothes. His flair was legendary: he was known for wearing Tibetan bakkhus, Astrakhan caps, and never stepping out without a sense of studied elegance. Even his wedding invitation became an event! It was printed as a replica of an ancient Bengali palm-leaf manuscript, complete with hardboard covers and an aged appearance, designed to evoke a sense of heritage and refinement.

But this aesthetic sensibility wasn’t always admired. Nirad C. Chaudhuri recounts a telling anecdote: when Amal sent out multiple editions of the wedding invitation, including a deluxe version for select recipients, one respected elder—known as "Mohit Babu," likely a figure of stature in Calcutta’s literary or bureaucratic circles—was offended to receive only the regular edition. For Amal, the gesture had likely been a matter of design and gradation; for others, it bordered on insult. It was a moment that illustrated how Amal’s fastidious taste, while admired by many, could provoke resentment among peers unaccustomed to such theatricality in social rituals.

“Although Amal Home went about in tramcars,” satirist Sajani Das observed, “he sat in them as if he was in a Rolls-Royce.”[1]

Born into the intellectually progressive Brahmo Samaj and part of what Chaudhuri called the “avant-garde in intellectual activities,” Amal had neither a university degree nor formal academic laurels. Yet, he was what one might call a cultural impresario. Chaudhuri described him as “a remarkable manager,” an “efficient” organizer with “impeccable manners… admired” even by those who found him overly meticulous or socially flamboyant.

To some, he was a dandy; to others, an aesthete with visionary standards. But to Amal, style was never superficial—it was philosophical. The way he entered a room, composed a sentence, or designed a publication reflected his core belief that beauty could dramatize ideas, and that culture should be lived, not just theorized.

Editor Extraordinaire: Journalism as Cultural Mission

Home’s political commitment took form in the pages of the Calcutta Municipal Gazette and later in the Hindusthan Standard. Chaudhuri credits him for crafting the vision and editorial direction of the Silver Jubilee commemorative issue in 1935—an “exquisitely produced” magazine filled with rare photogravures sourced from British agencies, which "the councillors could not say... was not a fine production."

Yet this refinement was also his downfall. The same extravagance that made him a magnetic impresario also put him in constant debt. And in journalism, his editorial decisions—like titling a piece on a German torpedo attack “German Kultur”—raised eyebrows for being "blatantly pro-British in a nationalist newspaper."

“He could certainly have been a Diaghilev in lines other than ballet.”[1]

One of his most acclaimed editorial efforts was the Tagore Memorial Special Number of the Calcutta Municipal Gazette (1941). A contemporary reviewer praised the issue for its meticulous archival approach and enduring scholarly value:

In his Tagore Memorial Special Number he has surpassed himself in many respects. ‘The Chronicle of Eighty Years—1861–1941’ and ‘The Chronology of Tagore’s Works 1878–1941’ would be specially useful to students of the Poet’s biography as well as to future writers of his life. This special number is remarkable for its wealth of information, the number and excellence of its illustrations—some from photographs obtained with difficulty, and for the high quality of some of the articles.[4]

This reception underscores Amal Home’s editorial acumen—not just as a cultural impresario but as an architect of Bengal’s print memory.

He also edited the 1933 centenary volume on Raja Rammohun Roy and, in 1961, was reportedly chosen by Prime Minister Nehru to help oversee the Tagore Centenary celebrations—an acknowledgment of his national stature.

In her introduction to Rammohun Roy: The Man and His Work (1933), editor Adrienne Moore credited Home’s “friendly cooperation since my arrival in India” and noted his “unfailing assistance... particularly in the publication of this volume.”[5]

A Tagorean Intimacy: Memoirs of a Devotee

Amal Home’s connection with Rabindranath Tagore was intimate, sustained, and vividly personal. A frequent visitor to Santiniketan, Amal was not just a witness to Tagore’s creative life but an active chronicler of it. He was part of the poet’s cultural circle—one who recorded the moods, musical improvisations, and spontaneous beauty that surrounded the Santiniketan years.

In his memoirs, Amal Home captured a vivid episode from the summer of 1914, when he was sipping tea with Dinendranath Tagore under an impending storm. Suddenly, Rabindranath appeared—his robe whipping in the wind, hair flying, glasses in one hand, singing above the roar of the monsoon. “His voice drowned the emergent storm,” Amal recalled, “[as he sang]… clutching his robe in one hand and his glasses in the other” . On another moonlit night, with most guests sent off to a nearby festival, Amal and a friend found Tagore alone on the verandah, singing quietly to himself—his body still as marble, composing what would become one of his immortal songs.[6]

These recollections are more than romantic tableaux. They offer insight into the immediacy of Tagore’s musical process, which depended heavily on Dinendranath Tagore. Dinendranath, his nephew and musical notator, was dubbed by Rabindranath as his “kandari o bhandari”—his helmsman and storekeeper. With a photographic memory, Dinendranath notated songs on the spot, often without any instrument. Without him, much of Tagore’s work would have been lost.

Amal’s admiration was also met with emotional intimacy from the poet himself. In a letter quoted by musicologist Partho Basu in Gayak Rabindranath—and later referenced in Reba Som's The Singer and His Song—Tagore lamented the decline of his singing voice in a note addressed to Amal Home:

“Where were you then when this voice was formidable—now that you have come, the tide of time has flowed on—in those days when I sang I had not started writing songs, and now that I write I have no voice left...”

Such remarks capture the trust Tagore placed in Amal. It was not simply artistic admiration, but the comfort of sharing decline with someone who understood the heights.

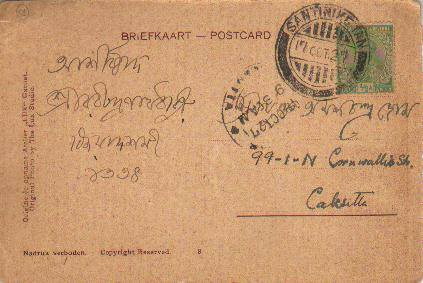

Beyond memory, Amal and his wife, Ila, also preserved a vast private collection of Tagoreana—letters, annotated manuscripts, postcards, and memorabilia. One such surviving postcard, addressed to their home on Cornwallis Street and postmarked from Santiniketan, confirms his presence in those fertile years. His deep friendship with Dutch musicologist Arnold Bake, another key Santiniketan figure, further affirms his place in that intimate cultural circle.

Picture Credits: Amal Home - Letters and His Writings.

One surviving postcard, addressed to their home on Cornwallis Street and postmarked from Santiniketan, serves as proof of his presence during those flowering years.

Amal’s friendship with Dutch musicologist Arnold Bake, a key figure at Santiniketan (1925–1934), further affirms his place in that intimate cultural circle. Photographs from the Bake archive show Amal—possibly with Ila or his brother Charu—seated beside the Bakes, bathed in the twilight of music and shared purpose.

A Face Returned: The Lost Portrait and Visual Afterlife

Portrait of Amal Home, circa 1940, Pastel on Board

Visual traces of Amal Home are vanishingly rare. Most of his correspondence—with Rabindranath and Rathindranath Tagore, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Subhas Chandra Bose, Amiya Chakravarty, Maitrayee Devi—is referenced only in memoirs or footnotes. One exception is a portrait that has resurfaced by an artist not yet traced: Amal, mid-life, contemplative, his gaze poised just beyond the frame. This portrait, likely taken in Calcutta during the 1940s, captures the man remembered by so many as exacting, elegant, and impossible to forget.

Cosmopolitan Circle: Friends, Photos, and Forgotten Fame

Amal’s circle extended across continents and disciplines. He counted among his acquaintances Subhas Chandra Bose, Jawaharlal Nehru, Suniti Kumar Chatterji, Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Amiya Chakravarty, and Rathindranath Tagore. And yet, he is largely absent from formal histories. Perhaps it was because he was difficult to categorise: Too refined for politics. Too flamboyant for academia. Too earnest for satire. A man of in-betweens.

Misunderstood Genius: The Tragedy of Unfulfilled Potential

Amal Home's paradox was that he was both deeply admired and widely disliked. Chaudhuri reflects on how he became a polarizing figure: “misrepresented and even vilified almost everywhere.” When asked how he managed to make so many enemies, Home "winced... and did not answer." This silence speaks volumes: perhaps a sign of his awareness that charisma without institutional power or wealth in colonial India often led to isolation.

“He was always considered to be arriving but never arrived.”

His contribution to the nationalist cause was often behind the scenes—never central but always shaping. From mentoring Nirad C. Chaudhuri during his first journalistic job, to influencing the editorial culture of Calcutta’s civic press, Home held powerful soft roles in shaping the aesthetic and political discourse of his time.

The Final Chapter: Illness, Obscurity, and Quiet Devotion

In his final years, Amal suffered a debilitating stroke and remained bedridden for over a decade. His wife Ila, stood by him with extraordinary devotion. His younger brother cared for him. He died in 1975. Before his illness, he wrote to Chaudhuri:

“Your friendship has enriched my life as hardly any other friendship has, and I shall ever cherish it.”

Legacy in Fragments: The Amal Home Omnibus Project

Today, Amal’s legacy survives in fragments: scattered letters, fading photographs, surviving memoirs, and rare municipal publications. His daughter, Amalina Dutta, is working to compile these into a proposed Amal Home Omnibus, including:

- Correspondence with Rabindranath and Rathindranath Tagore

- Letters from Sarat Chandra Chattopadhyay, Amiya Chakravarty, and Subhas Chandra Bose

- Annotated manuscripts, postcards (including one addressed to 99/1N Cornwallis Street), and editorial souvenirs

This work of recovery is not just personal—it is cultural.

Linguist and close friend Suniti Kumar Chatterjee described him as “Priya-darsha Amal Chandra” and “Ujjal Bangalee” — titles of affection and admiration. He wrote:

“Amal Chandra Home Ray... was familiar to all intellectuals throughout North India... as a scholar, a historian, a critic, a journalist, a patriot, a friend of men, a lover of arts, letters and music... and an intimate figure in the society of Bengal and India’s elite in his days.”

In his elegy, Nirad C. Chaudhuri grouped Amal Home with “those who showed greater promise for the future” but faded into silence. He called him “one more unfortunate.” But perhaps we can revise that judgment. In the portraits, the headlines, the footnotes, and now the archival rebirth—Amal Home still flickers. Still dazzles. He may have ridden a tram like a Rolls-Royce. But his truest vehicle was language, imagination, and memory. And it is through memory that we welcome him back.

References

[1] Chaudhuri, Nirad C. Thy Hand, Great Anarch!: India, 1921–1952. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988.

[2] Amal Home, Letters and Writings, Facebook

[3] Academy of Fine Arts Catalogue (1934-1935) Prinseps Archive.

[4] The Modern Review. Vol. 70, January–December 1941.

[5] Moore, Adrienne. Rammohun Roy and America. Calcutta: Sadharan Brahmo Samaj, 1942.

[6] Som, Reba. Rabindranath Tagore: The Singer and His Song. New Delhi: Kanishka Publishers, 2009.

.jpg)