If one were to visit Lalitha Lajmi’s home in her later years, one would find a space that quietly mirrored the artist herself. The walls were defining spaces in Lajmi's living room that spoke volumes about her creative personality. On the round table, a half-painted watercolour waited patiently, flanked by brushes and metal cups, its silent companions in the long hours of her nocturnal practice.

Behind her rocking chair stood a small universe of books. Shelves that traced nearly nine decades of her life and the many lives intertwined with hers. Her paintings hung beside those of her late daughter and brother; Kalpana Lajmi and Guru Dutt's film posters. Their works sharing the same light. And amidst it all, in that rocking chair that creaked with gentle insistence, sat Lajmi, draped in a saree, her eyes alert and searching. She spoke with quiet intensity, eager to share the stories that had shaped her — of Calcutta, of cinema, and of long nights spent painting while the world was still in slumber.

Lalitha Lajmi (1932–2023) was a veteran printmaker and painter whose creative oeuvre spanned over five decades of etching and printmaking, pen and ink drawings, oils, and watercolours. A largely self-taught artist, she continued to paint in her Lokhandwala home well into her late eighties. Her practice navigated the human predicament with an autobiographical undercurrent and a sustained engagement with psychoanalysis.

Childhood and Early Sensibility

Lalitha Lajmi recalls her childhood as a world alive with colour, sound, and performance. The family lived near Paddapukur Tank in Calcutta — a landscape of red earth, temple lamps, and the annual Parish Mela, where Jatra plays were performed through the night and stalls overflowed with painted clay figures, wooden toys, and pottery in deep reds, yellows, and greens. “The Baul singers used to come to our doorsteps singing beautiful devotional Bengali songs,” she wrote. “My grandmother would call me to give them a handful of rice.” [1] Such scenes —theatrical, and rooted in ritual — formed the earliest impressions of her visual and emotional world.

Her household was steeped in creativity. Her father wrote verse in English and quoted Shakespeare with ease; her mother wrote in Kannada, Marathi, and Bengali. Her uncle, the painter and commercial artist B. B. Benegal, designed cinema hoardings for Calcutta’s theatres and gifted her a paint box when she was five — an act she often cited as the true beginning of her artistic journey. Through Benegal, she and her brother Guru Dutt were introduced to the world of images, film publicity, and the art of storytelling. “He could get us passes for three or four films a day,” she remembered. Exposure to Prabhat and New Theatres cinema, to hand-painted posters and the glow of projected light, sharpened a visual sensibility that would later shape both siblings’ work — his in cinema, hers in print and paint.

Guru Dutt’s experiments with movement and shadow fascinated her. She remembered “peeping in and watching him do the shadow play in my grandmother’s room, late in the evening, where our deities were kept and the lamp was lit up.” [1] That early fascination with light, gesture, and the play between concealment and revelation would become a lifelong preoccupation in her own art.

Lajmi’s early interests, however, extended beyond observation. “There are some incidents that perhaps would have changed the whole course of my life,” [1] she wrote. At fourteen, she was almost recruited as a dancer for Discovery of India, a ballet organised by Rajen Shankar, Laxmi Shankar, and Ravi Shankar — an experience she remembered vividly, listening in awe as Ravi Shankar practised his riyaaz on the sitar. Two years later, Guru Dutt photographed her for Baazi while looking for a new face, but abandoned the idea. “So because I was not destined — or may not have been a good actress — today I paint, far away from the performing arts.” [1]

Even so, the sensibility of a performer remained central to her. She gave her first classical-music recital at eight at a Saraswat gathering, learned Manipuri dance, and later performed while studying at the Sir J. J. School of Art. This early engagement with rhythm and gesture would later surface in her imagery — the dancers, masks, and bodies that inhabit her prints and paintings, all reflections of a life first shaped by the performative and the poetic.

Early years in Bombay

When the Lajmi family moved from Calcutta to Bombay in the years following Independence, the city opened an entirely new visual world. For Lalitha, who had grown up amidst Jatra plays, Baul songs, and hand-painted cinema hoardings, this move marked the beginning of an enduring engagement with the creative world. She began studying Commercial Art at the J.J. School of Art. In 1948, she entered the orbit of what would become modern Indian art’s most influential circle. Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, in her handwritten notes, recalled that year as the moment she and Ambadas Gade joined the Progressive Artists’ Group. “Frequent visitors,” she wrote, “were Lalita Lajmi and Geeta Dutt (she had not married Guru Dutt then).” [2] The gatherings included Tyeb Mehta and V. S. Gaitonde, and ideas were exchanged freely in the small Bombay studios where modernism was taking shape. Though still finding her footing, Lajmi absorbed the energy of this milieu. It was her first close encounter with a community of practicing painters.

.jpg)

Lalitha Lajmi with husband Gopi Lajmi and brother Guru Dutt.

Image Courtesy: Lalitha Lajmi

Marriage and family life soon followed, interrupting this first period of discovery. When we interviewed her, she said“I got married very young. After that, I did not really have the time to follow my interests for a while.” [3] Yet, she remained drawn to art’s discipline. She recalls, " I was completely swept by the arts." After moving from Matunga to Colaba, she would often set off on her own to see art exhibitions. Around the same time, she began teaching art at two schools around Colaba: The Convent of Jesus and Mary and Campion. One of her etchings from the 1980s captures her vivid memory of the broken window outside the Convent School in Colaba, where she taught.

.jpg)

Through my Window by Lalitha Lajmi, Etching, 1984

Teaching remained her anchor through those years, but her artistic discipline was still taking shape. While teaching art at the Convent of Jesus and Mary and at Campion in Colaba, she continued to paint, selling her first oil to a German archaeologist for a hundred rupees. “You might sell something once or twice,” she later said, “but you can’t live on it.” Around this time, the Progressive painter K. H. Ara encouraged her to formalise her training so she could continue teaching. On his advice, she completed a B.Ed. in Art and later a Master’s, though Mumbai University then had no provision for art as a college subject.

Ara also helped her navigate Bombay’s art world. “He guided me and helped me with my first show,” she recalled, “and booked the Jehangir Art Gallery for me.” [3] Her first exhibition was a group show at Jehangir, followed by her first solo exhibition in 1961. These early shows marked her quiet arrival into the city’s artistic circles — long before her name would be associated with etchings and printmaking.

The Making of a Printmaker

One of her first known experiments with printmaking dates to 1969, when she began exploring the possibilities of the woodcut. A few years later, in 1973, she joined the evening classes at the Sir J. J. School of Art. “Back then, I was only doing oils and drawings,” she recalled, “and wasn’t very serious about printmaking since I wasn’t sure of the craft or method of doing it.” [3] And hence, in her first year, she learned to create linocuts, woodcuts, and etchings under her professor's guidance. She recalls it being a difficult medium to start with, and how to succeed, one must have steady hands.

It took her some time to learn the craft, but the real challenge, she later recalled, lay in the lack of materials. “At J. J., we didn’t have the proper things to work with then,” she said. “So I had these at home — nitric acid, a gas stove, and plates.” [3] The learning process was slow and exacting: she ruined several plates before mastering the method. But the routine of those years — teaching through the day and attending the evening classes from 5:30 to 7:30 — instilled a discipline that would come to define her later work. “The lights were very dim in the evening classes,” she said. “We had large presses for printmaking. The first method is that we have to do an aquatint and prepare the inks. Everything was done from scratch by the artist. All the prints you see are done totally by me — there was no help.” Though it was tiring, she worked through the night, often until two or three in the morning. “Preparing a plate would take about three weeks,” she said. “But I was pretty young in my forties, so it was alright.”[3]

.jpg)

Lalitha Lajmi, The Three Masks, 1973

As she developed her practice in her first year at J.J., this nocturnal rhythm had become inseparable from her art. One of the most striking works from this period, The Three Masks, emerged from this phase of quiet intensity. Kalpana, her daughter, born in 1954 and then a young theatre student, had begun to influence her imagery.

The concept of masks came to me because of my daughter, Kalpana. She was in college and good at dramatics. I would often attend her rehearsals and was intrigued by her interest in theatre. But I started doing masks subconsciously. My masks were humane, with feelings and emotions, unlike the decorative kind, which I do not like.

Lalitha Lajmi, An Interview with Lalitha Lajmi, Prinseps Archives

Between 1974 and 1976, Lajmi produced a body of nineteen abstract drawings — meditations in black and white where form, nature, and psyche intersect. Stones, leaves, and streams seem to dissolve into shifting planes of light and shadow; in some, faint profiles and fallen birds surface within the dense textures. These drawings were never exhibited and were shown only to Prabhakar Barwe, whose quiet intellect and sensitivity to form she admired.

Yet this was also a period of inner restlessness. “I was doing two different kinds of work,” she recalled, “and that disturbance made me go to a psychologist.” [4] Soon after, she abandoned abstraction entirely and turned decisively to printmaking.

Lajmi's Nocturnal Practice

When the evening classes at J.J. ended after three years, Lajmi continued teaching at the convent from eight to four — “so the whole day was gone,” she said. Determined to keep working, she decided to buy her own press. “I would do all my prints at night and work after dinner from nine to two every day. Preparing a plate would take me about three weeks.” [3]

Her method was intuitive rather than planned. “I have always been a highly imaginative artist who would work on the spot — there is nothing preconceived in my art,” she said. “Within a short period, my hand was steady.” Etching, however, was an unforgiving medium. “Lines are engraved with acid, and it’s difficult to remove them if you make a mistake. I would use an instrument to rub the lines, but it takes a long time.” [3]

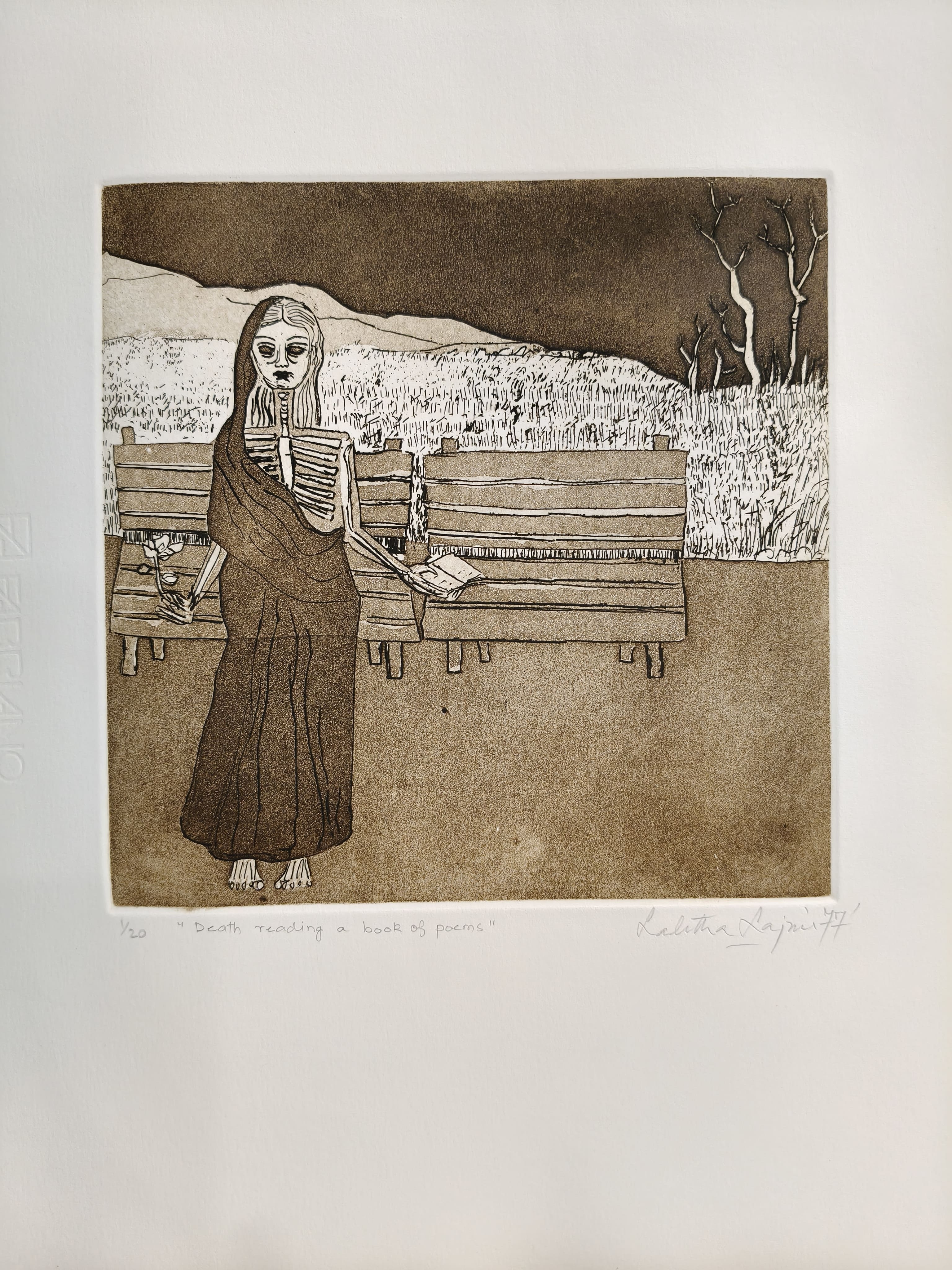

Lalitha Lajmi, Death Reading a Book of Poems, 1977

The process was self-taught, evolving through trial and repetition. “One has to be very careful because when ink is used on the plates and on the sides, it has to be absolutely clean white. And that takes a long time to learn,” she said.

I used to take the prints on Saturdays and Sundays and prepare the whole thing at night. In those days, we didn’t have enough water, but we did have huge tubs filled with cold water so that I could dip the paper into it. The lack of sleep did not deter me because my body got so used to staying up till two or three in the morning. Even today, I have the same habit.

Lalitha Lajmi, An Interview with Lalitha Lajmi, Prinseps Archives

In those quiet, solitary hours, she built something rare: an independent practice run entirely by hand. At a time when printmaking studios were few and almost entirely male, Lajmi became one of the first women in Bombay to establish and operate her own printmaking press.

Life is full of ups and downs. It’s never smooth for any of us — perhaps that’s why my work turns to death so often. [5]

One of the defining works of this period, Death Reading a Book of Poems (1977), was made while she was undergoing psychoanalysis. “When I created this work, I was going through analysis,” she said. “It can be rather harrowing in the beginning, but what comes out of the subconscious are disturbing feelings and dreams reflected in my work. I had to speak about these dreams to the analysts; during that period, I uncovered other parts of my creativity, including poetry.” [6]

Her engagement with psychoanalysis also brought her into contact with writers and poets. “I knew quite a few poets back then,” she recalled. “Kamala Das would invite not just poets but people from the creative field on a Saturday and serve tea and snacks, and would ask us to recite a few lines of whatever we had written. I was introduced as a creative person and artist in those gatherings. During psychoanalysis, apart from your dreams, you realise your creativity from within and begin writing poems. And I did write a few lines, but I was always shy to show them.” [6]

Artist Circles and Exhibitions

Lajmi soon entered the orbit of artists who would come to define India’s modern movement. “You must have heard of Nasreen Mohamedi,” she said. “I had met her a couple of years earlier, and she became a very dear friend.” [3]

Lajmi spent a period working in Baroda, at the Maharaja Sayajirao University (MSU), where she encountered many of the city’s young artists. “The school I was in had classes from seven to two,” she said, “and then it was free for the artists to come and work with graphics or the press as they pleased. The college was open day and night, and that was very rare.” There, she met Bhupen Khakhar, then still working in an office; Vivan Sundaram, Nasreen Mohamedi, and Gulam Mohammed Sheikh, who was teaching at the time. “I have met everyone,” she said. “The best students came from Baroda.”[3]

Her closest artistic dialogue, however, remained with Prabhakar Barwe, whose intellectual and formal rigour she deeply admired. “Whenever I had my sessions with my analyst,” she said, “I would go to the Weavers’ Service Centre and have a cup of coffee with Barwe and talk to him. We thought in the same way.” [3]

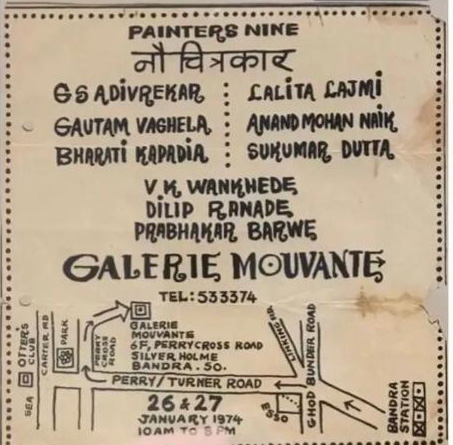

In 1974, she participated in Painters Nine (Nau Chitrakar) at Galerie Mouvante in Bandra alongside Barwe, Bharati Kapadia, Anand Mohan Naik, Gautam Vaghela, Sukumar Dutta, and others — one of her earliest group exhibitions after her 1961 solo at Jehangir Art Gallery.

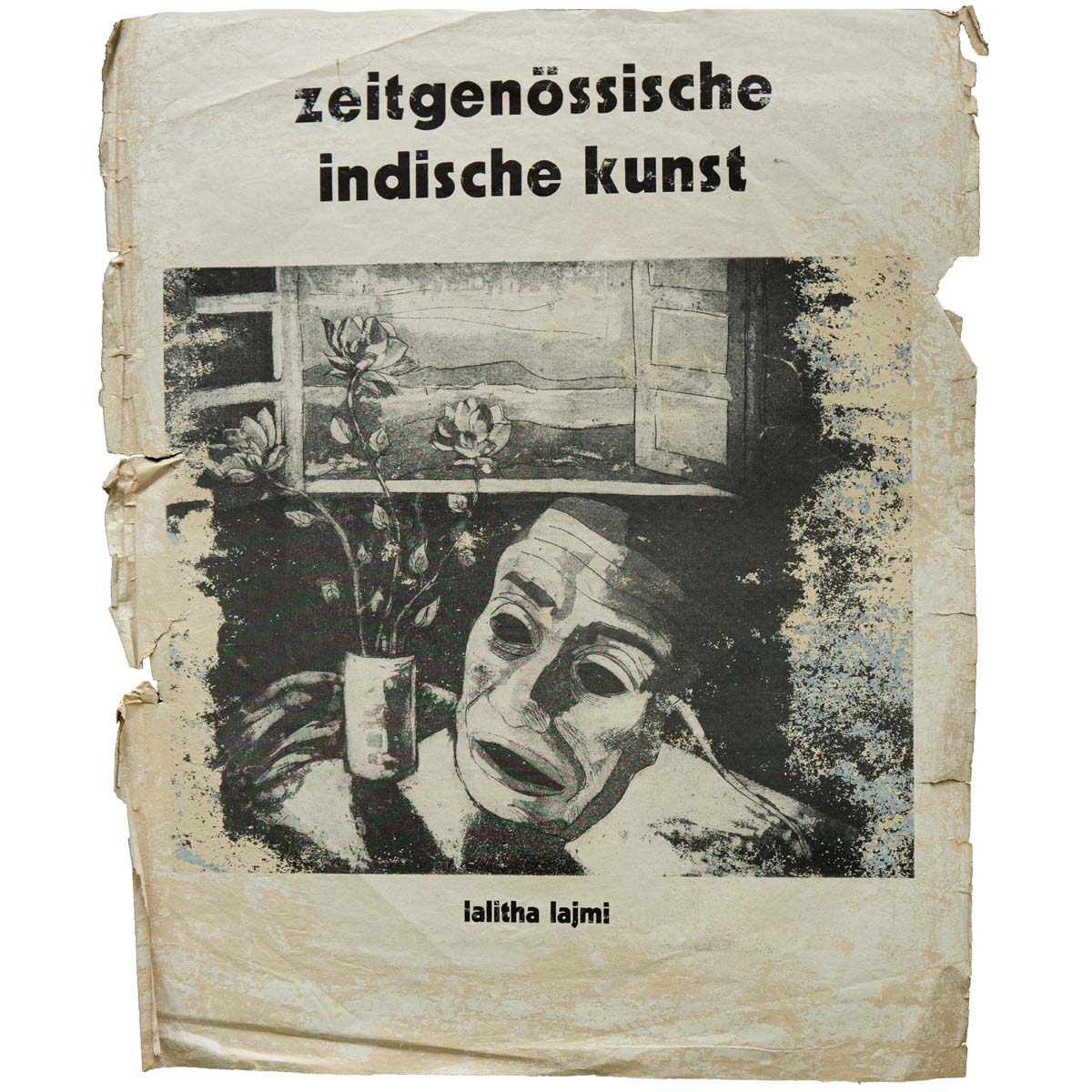

Catalogue cover featuring Lajmi’s work from “Zeitgenössische Indische Kunst” Germany, 1983.

Image Courtesy: Lalitha Lajmi Estate

Her prints travelled widely in the following decade. In 1983, she received an ICCR travel grant to Germany, where her works were included in Zeitgenössische Indische Kunst (Contemporary Indian Art).

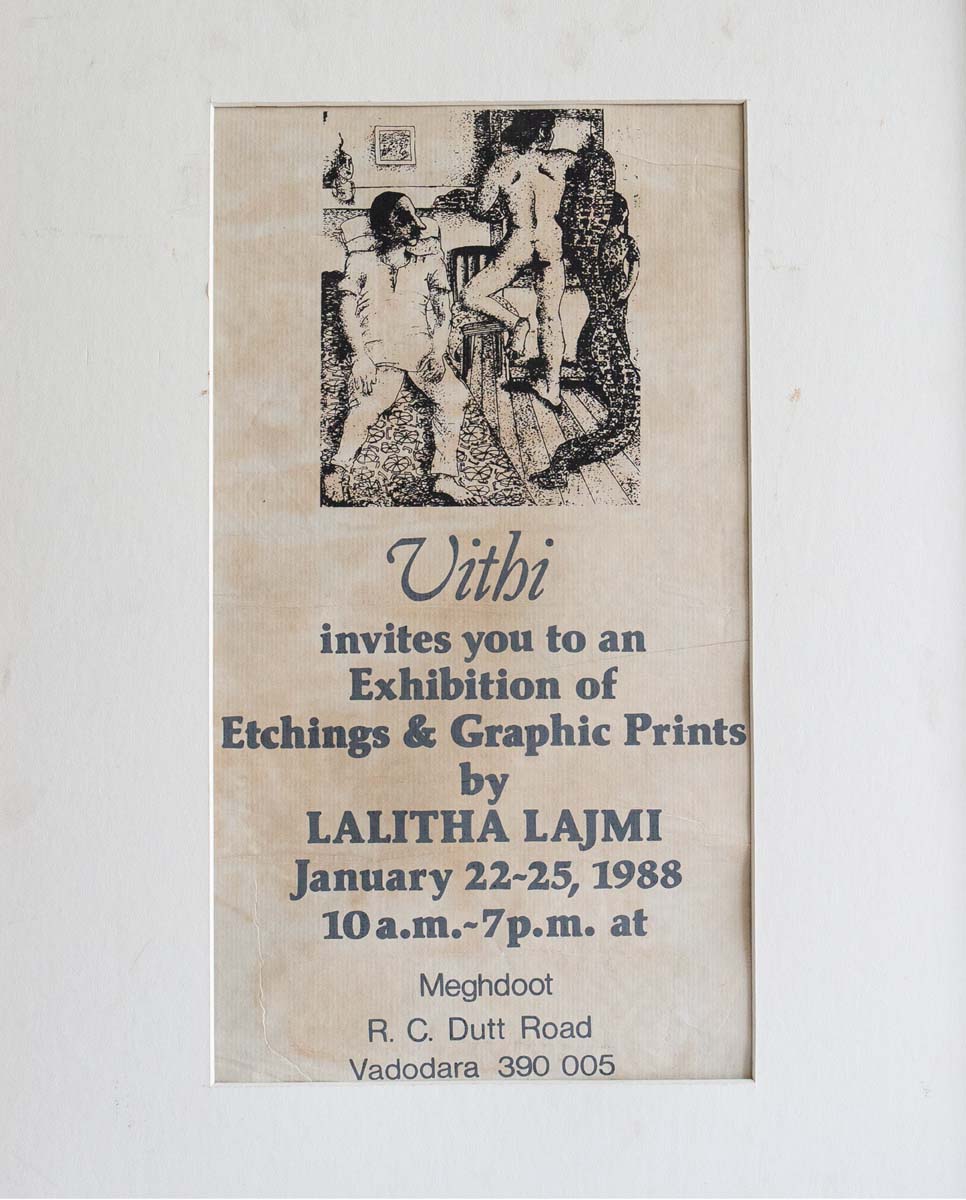

Poster for Lalitha Lajmi’s solo exhibition “Etchings & Graphic Prints,” Vithi Gallery, Vadodara, 1988.

Image Courtesy: Lalitha Lajmi Estate

Five years later, she held her solo exhibition Etchings and Graphic Prints at Vithi Gallery, Baroda, followed by showings at NGMA Mumbai, Pundole Art Gallery, Prithvi Art Gallery, and Apparao Gallery, Chennai. By the late 1980s, her etchings were represented in collections of the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), the CSMVS Mumbai, and the British Museum, affirming her position among the artists who brought psychological depth and quiet precision to Indian printmaking.

From Etching to Oil (1990s): From the Mask to the Body

By the early 1990s, the theatre of the mask had moved inward. “I continued with masks for a long time,” she wrote, “but much later I came to the depiction of the body. The masks had disappeared and now they were within.” [3] In these works, the melancholic etchings give way to charged interiors — seated figures, doubles, and watchers placed in taut relation. Colour becomes structural: saturated blues and reds holding psychological temperature, while the gaze and hand carry the drama once borne by overt props.

.jpg)

Lalitha Lajmi, Death also has a Mask, Oil on Canvas, 1999

This period also marks her return to oil on canvas after years of disciplined printmaking. “I sold my first oil to a German archaeologist for 100 rupees,” she once recalled, “and my drawings for fifteen.” [3]

As I unfolded mask after mask within me, there were other concerns in exploring relationships, the interiors and exteriors of architecture, and the disturbances in the practice of psychoanalysis. From the mask, I came to the body.

Lalitha Lajmi

The chromatic depth of oil allowed her to translate the etched line’s precision into layered painterly space — bodies edged by shadow, a mask held rather than worn, performers staged as private allegories rather than spectacle. The works kept faith with her printmaking grammar.

Dream Journals and the Language of Watercolour

By the end of the 1980s, her notebooks began to record a deepening introspection. On a hot afternoon in 1989, she wrote, “The past seems to haunt me all the time.” A blackout had left her struggling to paint. “Whatever I do, I am unhappy,” she confessed. “I show birds flying away in many of my paintings — I suppose that is me.” [7]

The diaries of this period reveal an artist confronting solitude as both burden and material. In one dream, she found herself trapped in a room filled with flowers. “Am I gone?” she wrote. “No — the flowers are only symbols of loneliness, loneliness.” [7] The line might well describe her late work itself — emotion transmuted into image, always filtered through symbol, colour, and dream.

Lalitha Lajmi, Untitled, 2014, Watercolour on Paper

It was during these years that Lajmi’s focus shifted toward watercolour — a medium she described as “closest to the subconscious.” “From the mask, I came to the body,” she said, “and from the body, to the dream.” [3]

.jpg)

Lalitha Lajmi, Mother and Child, 2017, Watercolour on Paper

I didn’t deliberately include this theme of a mother and child. A lot of my work happens at a subconscious level.

Her late compositions hover between figuration and reverie: acrobats, mothers, children, and doubles of herself appear in translucent washes of blue and red — the two colours she kept returning to. “I wanted to delete colour from my work,” [7] she wrote. Blue and red were enough — the colours of cold and heat, of life and its shadow.

Lalitha Lajmi, Dream, 2017, Watercolour on Paper

Among these, a series simply titled Dream embodied her most intuitive method. “I don’t plan,” she explained. “Once I see the paper, I begin to draw, and the thoughts and images come to me.” One large watercolour from this series — completed over a month — “looked like oil,” she noted, “but was done totally in water.” [8]

These late watercolours carried forward the discipline she had built over decades — working alone, often at night, in her home studio. She described the process as intuitive but sustained: beginning without a plan, painting for hours until an image surfaced. The medium suited her rhythm; it allowed freedom without physical strain, precision without the rigour of the press. In these years, watercolour became her primary language.

When we last visited Lalitha Lajmi, a half-painted watercolour rested on the table in her suburban apartment. The brushes stood in their holder, two cushions propped up her chair — everything in its familiar place, as if she had only stepped away for a moment. Until the very end, she continued to work with quiet resolve. The nocturnal habit remained: solitary, steadfast, and sustained by art’s quiet necessity. “Art,” she once said, “is like breathing; I can’t live without it.” [9]

References

[1] Lalitha Lajmi. Lalitha Lajmi's notes on Guru Dutt and her childhood. Prinseps Archive. 2022.

[2] Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya. Bhanu's handwritten notes. Prinseps Archive.

[3] Lalitha Lajmi. An interview with Lalitha Lajmi. Prinseps Archive. 2022.

[4] Lalitha Lajmi. Lajmi on her rare abstracts. Prinseps Archive. 2022.

[5] Lalitha Lajmi. Lalitha Lajmi Artist. Hugh M Hood Archive. 2018.

[6] Lalitha Lajmi. Conversation with Prinseps. 2022.

[7] Lalitha Lajmi. Thomas, Skye Arundhati. Inside the Surreal Feminist Theater of Lalitha Lajmi. Artnet News. April 23, 2025.

[8] Lalitha Lajmi. Lalitha Lajmi at The Art of India. 2022.

[9] Lalitha Lajmi. Bhattrai, Sushmita. My Daughter, Kalpana Lajmi. Seniors Today. February 14, 2020.