Hailed as the father of modern Chinese painting, Xu Beihong’s vast oeuvre reflects a rich confluence of cultural influences absorbed during his travels. Among these sojourns, Xu’s spirit of cultural fusion found new ground in 1939, when he was appointed the first Chinese visiting professor at Rabindranath Tagore’s Visva-Bharati University in Santiniketan, West Bengal.

.jpg)

Xu Beihong, Self-portrait, 1922, charcoal on paper (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

At the opening of one of Xu’s exhibitions, he described Santiniketan as a “place which corresponds to my ideal of a center of art and culture.” (1) As he traversed across the lengths and breadths of the nation, he masterfully synthesised Chinese, western and Indian aesthetic traditions, resulting in some of his most celebrated works, a connection rarely explored in art history.

EARLY LIFE

After ten years of hard work, grandfather was able to build himself a small cottage by the river to shelter from the weather. My father was born in that cottage which was simple and crude. But he felt fortunate that nature lavished boundless beauty on all of us with the South hill as a painted screen in the background and the Tang river like a flowing path… (2)

- Xu Beihong

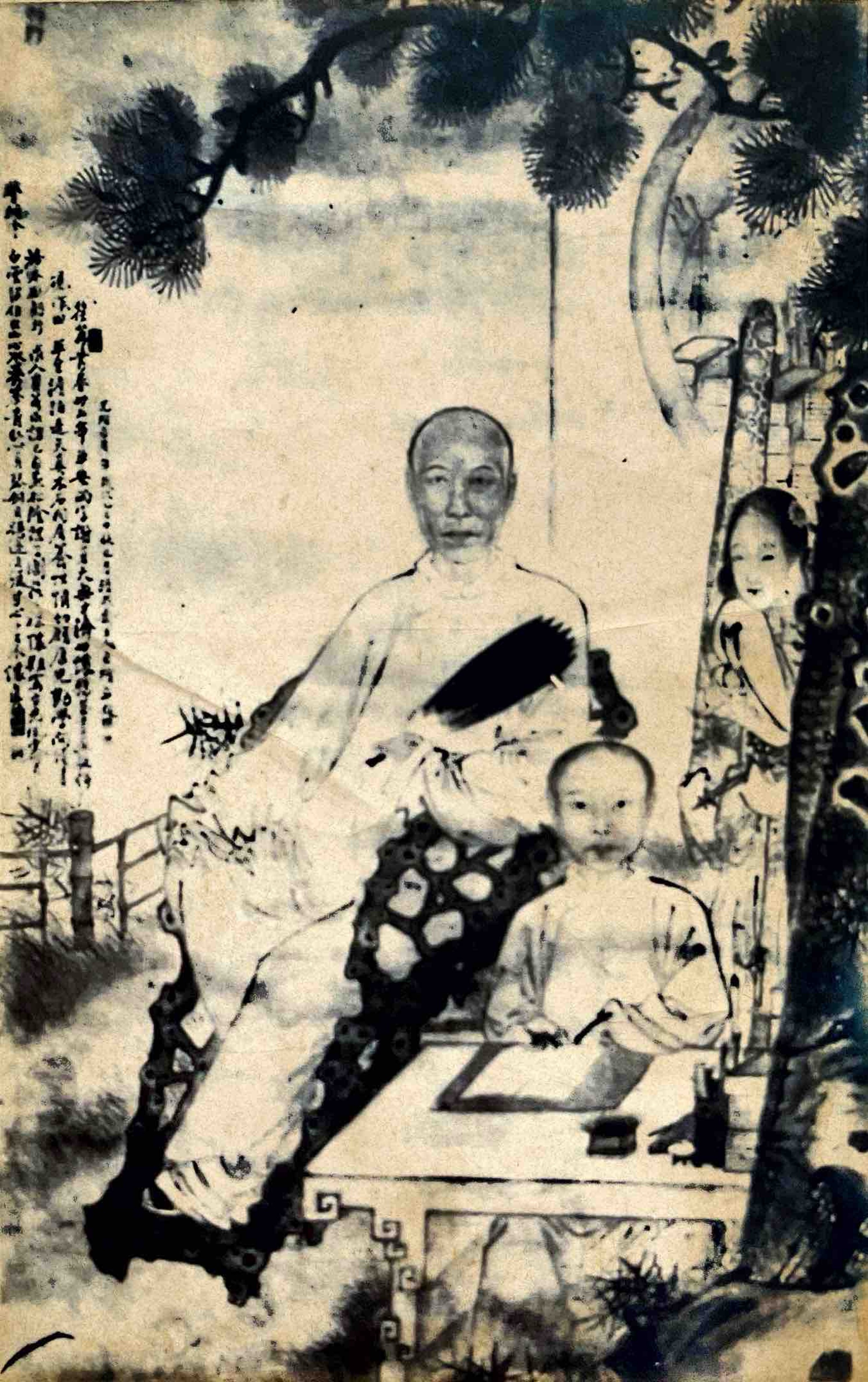

Born in 1895 into a modest family in Yixing, Jiangsu Province, a village often affected by seasonal floods, Xu Beihong spent his childhood toiling on the family farm. Yet he developed a love for art through his father, Xu Dazhang, a self-taught landscape and figure painter who introduced him to traditional Chinese art and calligraphy, laying the foundation for what would become a lifelong pursuit.

Xu Dazhang (Xu Beihong’s father), Coaching the son, 1901 (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Following in his father’s footsteps, Xu Beihong began painting portraits at a young age, drawing inspiration from artists of the late Qing dynasty. To make ends meet in the wake of recurring floods, he and his father would travel from village to village to sell their paintings.

In 1912, his father fell gravely ill, forcing them to return home. Xu, still in his teens, stepped into the role of the sole breadwinner, teaching art at local schools to support the family. Shaped by early hardships and later, the melancholy of losing his first child, he changed his birth name, Shoukang (meaning “longevity and health”), to Beihong, a name drawn from the image of a lone, sorrowful goose in Chinese poetry and folklore. (5) While horses would later define his public image, the goose remained a rare and private motif, one that appeared only occasionally in his body of work.

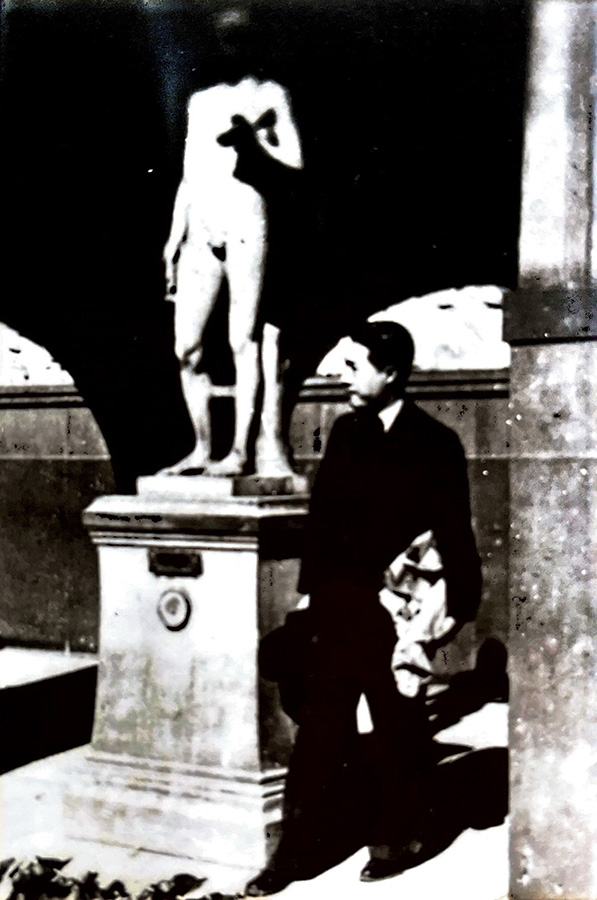

His artistic interests deepened when he received a government scholarship to study in Europe in 1919. He enrolled at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris and travelled through Germany, Belgium, Italy, and Switzerland, studying sketching and oil painting. From observing animals in European zoos to mastering classical Western techniques, Xu worked steadily to merge these new influences with Chinese ink traditions. The result was a body of work that bridged two artistic worlds and helped define a new era in modern Chinese art.

Xu Beihong at his alma mater, the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris, 1919 (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Xu Beihong returned to China in 1927 and began teaching art at National Central University. He emerged as one of the first Chinese artists to give visual expression to a modern national identity through art in the 20th century. His time in Europe not only shaped his technique but also deepened his conviction in the need for reform within Chinese painting.

In his essay Methods to Reform Chinese Painting, he argued for an approach that would “preserve those traditional methods which are good, revive those which are moribund, and amalgamate those elements of Western painting which can be adopted.” (4) His practice reflected this vision, rooted in classical Chinese aesthetics, yet responsive to new forms and ideas encountered abroad.

Xu Beihong, Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Warriors, 1928-1930, oil on canvas. (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

XU BEIHONG JOURNEYS TO INDIA

Away from the bustle of colonial Calcutta lay Santiniketan, “the abode of peace,” named and founded in 1863 by Debendranath Tagore as a quiet ashram for meditation. In 1888, he established the Brahmavidyalaya (school) and a library here, sowing the seeds for an educational centre rooted in both spiritual and intellectual growth.

In 1901, his son Rabindranath Tagore carried this vision forward by founding the Brahmacharyasrama with just five students. This small experimental school, later known as Patha-Bhavana, emphasised open-air learning in close harmony with nature. Two decades later, in 1921, this ethos expanded into Visva-Bharati University, a pioneering institution where Indian and world cultures could meet on equal terms.

Sundrenched yellow walls nestled among sprawling banyan trees give the campus a quiet, timeless beauty. Walking into Visva-Bharati in Santiniketan feels like stepping into one of Tagore’s poems. Terracotta-hued leaf patterns climb its pillars, windows open out to gardens, and classes often take place under the shade of trees. Tagore envisioned a place where learning was not confined by walls, where the arts, music, and literature flourished alongside the pulse of nature, and where education was a bridge between India and the world.

.png)

Rabindranath Tagore with teachers of Visva-Bharati University (Credit: Prinseps).

The laureate fervently believed that learning was the essence of life, thus emphasising a harmonious relationship between children and nature. In his essay “My School”, Tagore says, “We all know children are lovers of the dust; their whole body and mind thirst for sunlight and air as flowers do… Our childhood is the period when we have or ought to have more freedom — freedom from the necessity of specialisation into the narrow bounds of social and professional conventionalism.” (7)

With a low-slung profile, the institution weaves together man and nature in an architectural framework that quietly rebels against colonial styles popular at the time.

At an invitation from Tagore, Xu Beihong arrived in Santiniketan towards the end of 1939 to organise exhibitions and deliver lectures at Kala Bhavana (fine arts division at Visva-Bharati). The art school sought to receive a nuanced understanding of Chinese art, and Xu’s arrival offered that. The artist delivered lectures in Chinese ink brush painting and calligraphy, sharing his experience and refined techniques with the students of Kala Bhavana.

Santiniketan’s environment provided ample open grounds for Xu Beihong to appreciate the nature of the region. He closely observed the unique flora and fauna Santiniketan had to offer, subjects that informed his artistic practice. He produced several studies of the vivid red blossoms on silk-cotton trees, one of which stood prominently in front of the Chanda residence.

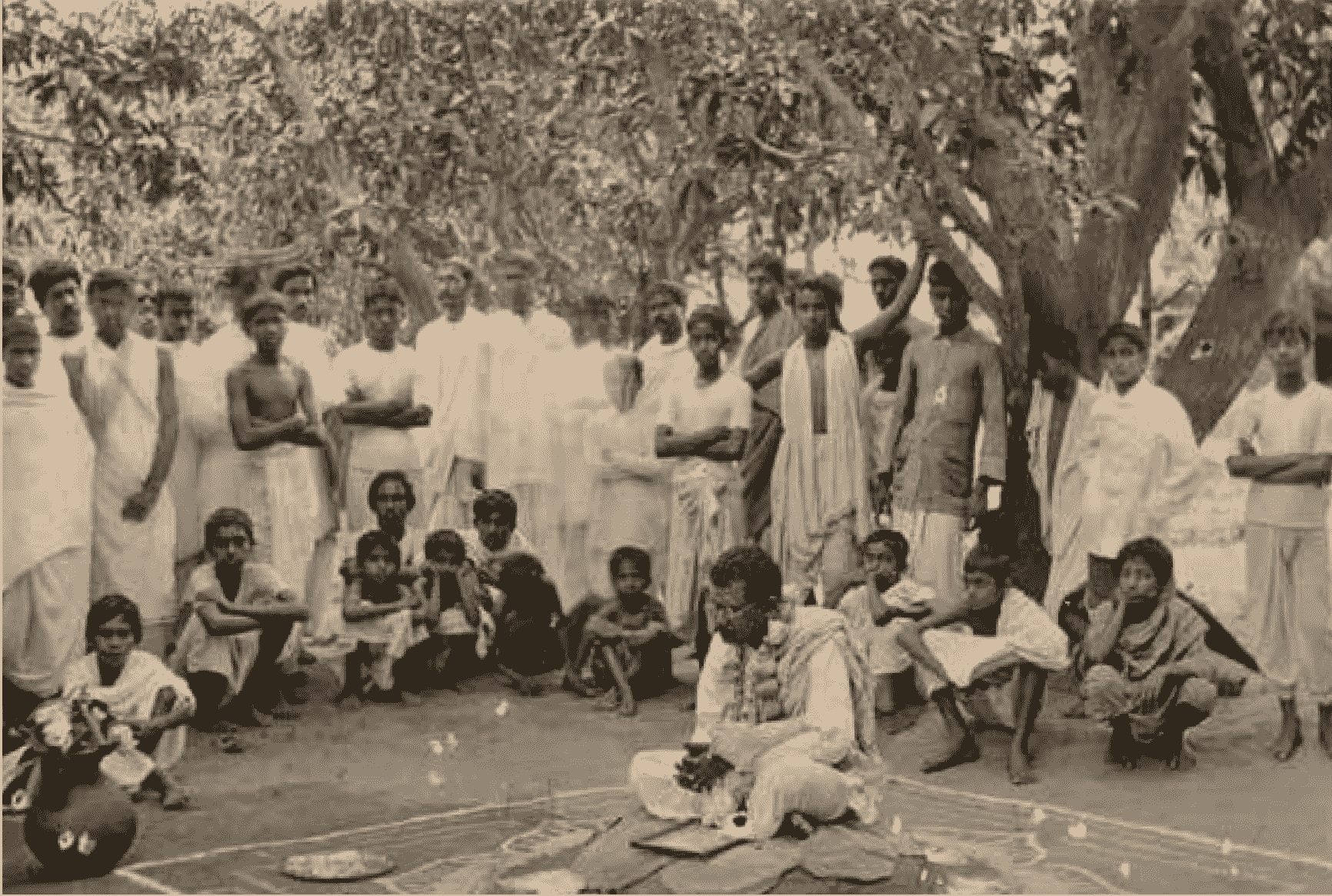

Nandalal Bose being felicitated at Santiniketan’s Amrakunja (Credit: Prinseps).

Anil Chanda, Secretary to Rabindranath Tagore, and his wife Rani Chanda developed close friendships with Xu Beihong during his stay. In the evenings, Xu would often be found conversing with his host, Professor Tan Yun-Shan, founder of Cheena Bhavana (the Institute of Chinese Language and Culture at Visva-Bharati), sharing anecdotes and voicing his deep concern for his homeland, which was then under Japanese invasion.

A golden era for the university, luminaries like Nandalal Bose, Ramkinkar Baij, Gauri Bhanja, and Benode Behari Mukherjee were active contributors in shaping the Kala Bhavana at the time. Tagore himself, then in the terminal years of his life, was a powerful presence, personally observing and engaging with the students and educators at the university.

.jpg)

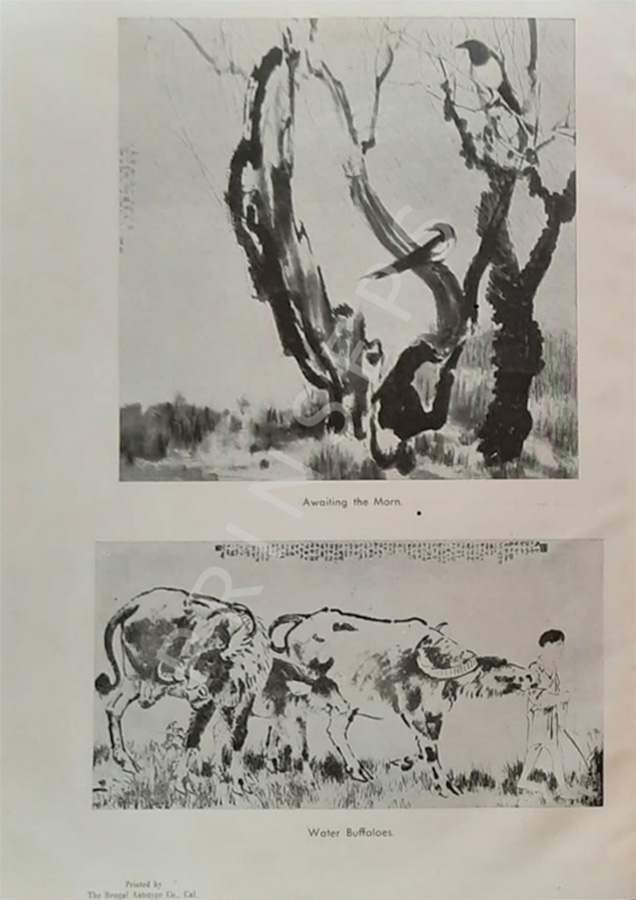

Pages from Xu Beihong’s 1940 exhibition catalogue.

Xu Beihong held a major exhibition in Calcutta in 1940, initiated by Rabindranath Tagore under the joint auspices of the Indian Society of Oriental Art, Calcutta, and the Sino-Indian Cultural Society, Santiniketan. Featuring 206 of the modernist’s artworks, the exhibition showcased his vast range of fauna paintings, including ‘Flying Storks’, ‘Geese’, ‘Water Buffaloes’, and a collection of his renowned horse paintings. Numerous portraits, landscapes, and figurative works conveyed his mastery across pastels, sketches, Chinese ink brush, and Western oil painting.

Paintings from the Ju Peon (Xu Beihong) exhibition catalogue, 1940.

The exhibition was supported by prominent Indian artists like Nandalal Bose, who wrote an appreciation for Xu Beihong’s exhibition catalogue. Bose said, “His visit to India affords to our own artists and art-students a very precious opportunity of knowing, through his paintings, the soul of China.” (3) Prominent artist and founder of the Bengal School of Art, Abanindranath Tagore, opened the show.

During the exhibition, Xu said, “The whole world should make a pilgrimage here (Santiniketan) to breathe the joyful atmosphere of creative endeavour undertaken here under the direct inspiration of India’s great poet. My visit here is that of a pilgrim. I have come not to give but to receive the great gifts that India may have to bestow upon my country and people as she did in the days gone by.” (1)

Along with organising cultural events, getting acquainted with notable figures, delivering lectures about Chinese ink brush techniques, and admiring the rolling Himalayas, Xu produced some of the most celebrated paintings in his oeuvre during his artistic pursuits in India. This includes “Portrait of Rabindranath Tagore”, “ Portrait of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi”, “The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains", depictions of the Himalayas, and his famous ink brush paintings of horses.

INDIAN INFLUENCES IN XU BEIHONG’S ARTWORKS

The walls of Kala Bhavana in Santiniketan witnessed a friendship steeped in mutual respect and admiration blossom between Rabindranath Tagore and Xu Beihong. While Xu was moved by Tagore’s sensitivity towards the Chinese War of Resistance, Tagore appreciated the artist’s symphonic lines and mounting figures.

In rhythmic line and colour, China’s great artist Ju Peon (Xu Beihong) has offered us an immemorial vision without sacrificing the regional and the unique which have met in his own experience. (3)

-Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore with Xu Beihong (Credit: Institute of Chinese Studies).

In 1940, Xu Beihong painted an ink brush portrait of Rabindranath Tagore, drawing from numerous preparatory sketches he had made to capture the poet’s likeness and creative spirit. This was exemplary at a time when creating detailed portraiture from life was new in classical Chinese ink brush painting.

_(1)_(1).png)

Xu Beihong, Portrait of Rabindranath Tagore, ink and colour on paper; Portrait of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, charcoal on paper,1940 (Credits: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

The artist’s portrait studies often emphasised the precise rendering of his subject's features and expressions. In a Western-style study of the female sovereign of Bihar, he drew her face to capture her quiet inner strength. In the final painting, Xu retained the contours of her frame while rendering her sari and arms with stylised Chinese brushstrokes, adding a sense of fluidity. .jpg)

Xu Beihong, study for “Portrait of an Indian Lady”, 1940, charcoal and ink wash on paper (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

During Beihong’s stay in India, he travelled to Darjeeling, where he created one of his most renowned paintings. “The Foolish Old Man Who Removed the Mountains” is based on a Chinese fable from the classic Liezi that narrates the story of a man determined to remove two mountains blocking the views from his doorway. The man earnestly believed that the task was achievable by him and his successors, reflecting Xu’s belief in the Chinese people to emerge victorious in the War of Resistance with resilience and strength. (2)

The painting is a defining example of how rural life is woven into the Chinese themes of some of Xu Beihong’s works. At the centre of the composition is a group of village men, of whom the fifth, seventh, and eighth figures are seen wearing dhotis. A herd of elephants, likely domesticated for labour, also whispers possible references taken from Indian rural life. Xu marries the best of Sino-Indian traditions to narrate the story.

.jpg)

Xu Beihong, The Foolish Man Who Removed the Mountains, ink and colour on paper, 1940 (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

In preparation for this large-scale project that was completed over three months, Xu Beihong produced more than a dozen charcoal studies of the human form during his stay in India. The painting marked a milestone moment in the history of Chinese brush painting, featuring nude figures to portray resilience and strength through the men’s arduous digging.

.png) Studies for “The Foolish Man Who Removed the Mountains,”, 1940 (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Studies for “The Foolish Man Who Removed the Mountains,”, 1940 (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Xu Beihong journeyed north to the Himalayas from Darjeeling on horseback, despite extreme temperatures and high altitudes. Mesmerised by the sun peeking through the snow-capped mountains at sunrise, he painted the landscape in oil. The painting features a river navigating its path through dense foliage against the backdrop of the towering Himalayas..jpg) Xu Beihong, Morning scene of the Himalayas, 1940, oil on canvas (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Xu Beihong, Morning scene of the Himalayas, 1940, oil on canvas (Credit: Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Xu Beihong had a deep affinity for depicting animals, especially horses and birds, which formed a central part of his oeuvre. His works were grounded in meticulous anatomical studies, and inscriptions and seals in his paintings often reveal symbolic or analogical meanings. His vast collection of horse paintings alone is said to number around a thousand works, each rendered with remarkable depth and vitality..jpg) Xu Beihong, Six Galloping Horses,1942, ink and colour on paper (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Xu Beihong, Six Galloping Horses,1942, ink and colour on paper (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Exemplary of this is Xu Beihong’s artwork ‘The Horse’, painted in celebration of Rabindranath Tagore’s recovery from illness. The inscription on the painting reads, “November 1940. Beihong painted this to congratulate Tagore on his recovery from his illness. Gentle breeze and beautiful sun. The celestial and human worlds were celebrating.” Beside the spirited horse painted in graceful brushwork, one of the seals read, “Brilliant and fluid”, expressing joy. (1)

During his time in Darjeeling, Xu Beihong traversed vast plains, even long distances to Kashmir on horseback. The horses in India caught Xu’s admiration, graceful and sturdy with long necks, muscular chests, pointed ears, and lustrous coats. .jpg) Xu Beihong, Galloping Horse, 1941 (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

Xu Beihong, Galloping Horse, 1941 (Credit:Xu Beihong Memorial Museum).

A closer look at his horses, post his visit to India, points towards a significant shift in the stature of equines, an animal he connected with since his childhood. They now assumed more dynamic forms, in contrast to the plump and domesticated portrayal of horses in classical Chinese art. Xu reworked their shape to flaunt slender and extended legs, brawny builds, and captured in galloping poses, as seen in his work “Galloping horse”.

Xu Beihong’s time in India was, however, more than an artistic interlude. It was a confluence of Sino-Indian exchange, where brushstrokes bridged two ancient cultures, leaving behind a legacy of shared creative spirit and untapped stories to explore.

References:

- Xu Fangfang, "Discovering My Father Artist Xu Beihong’s Experience in Santiniketan, India", Institute of Chinese Studies, 2019

- Xu Beihong: Pioneer of Modern Chinese Art, Denver Art Museum

- Exhibition of paintings by Ju Peon, The Indian Society of Oriental Art &The Sino Indian Cultural Society, 1940

- Sue Wang, "Reproduction of Realism: Xu Beihong’s 118 Representative Works Debut at NAMOC", CAFA Art Museum, 2018

- Xu Beihong: 15 Facts About the Chinese Painting Master, Sotheby's

- Dr. Ritwij Bhowmik, "Xu Beihong and India: An Alliance Never Explored", International Journal of Arts, Humanities and Management Studies, vol. 1, no.4, 2015

- Rabindranath Tagore, "My School", Lecture delivered in America; published in Personality London: MacMillan, 1933

- Santiniketan: Visva-Bharati University

- Ka. F Wong, Reimagining China: History Painting of Xu Beihong in Early Twentieth Century, University of Hawai'i, 2004

- Artist Xu Beihong and His Family in Mao's China, (Stanford University, Department of Art & Art History, Center for East Asian Studies, 2019)

- "Daughter of Chinese Picasso decodes painter's work at Visva Bharati", Times of India, July 22, 2019

- Portrait of Tagore, Google Arts and Culture

- The Foolish Old Man Moves a Mountain, Google Arts and Culture

- Galloping Horse, Google Arts and Culture

- Beihong China Arts

- Xu Beihong, China Online Museum

- Xu Beihong, Wikipedia

- Xu Beihong, Britannica