Manjit Bawa is most often approached through his mythic protagonists—Krishna, animals, lovers—held in suspension against vast, luminous grounds. Yet the language that carries these narratives begins earlier, as form: rounded, pliant, weightless. The 1977 abstract canvas Untitled (Free Floating Form) under discussion foregrounds the unit before it becomes figuration. It is not an outlier, separated from Bawa’s later world; it is a concentrated glimpse of the grammar he would go on to expand.

Manjit Bawa, Untitled (Free-Floating Form), 1977, Oil on Canvas

Manjit Bawa, Untitled (Free-Floating Form), 1977, Oil on Canvas

Ravi Jain/ Dhoomimal Family Collection

Born in Dhuri, Punjab, in 1941, Bawa trained at the School of Art, Delhi Polytechnic between 1958 and 1963, before moving to England in the mid-1960s, where he studied and worked as a silkscreen printer. His early formation coincided with a period in which abstraction dominated art-school discourse, while figuration was increasingly marginalised. Bawa resisted this orthodoxy. Reflecting on those years, he later recalled the pressure to conform:

Being a turbaned Sikh from an ordinary middle-class family was daunting enough, but to strike out against the prevalent forces of Cubism and the iconic Klee was to really ask for big trouble… I was obsessed with one driving need – to create my own painterly language. [1]

This insistence on language rather than style frames the importance of the 1977 abstract canvas. What is at stake here is not abstraction as an end in itself, but abstraction as a site of construction—a laboratory in which Bawa tests the formal unit from which his figures would later be built.

Serigraphy and the architecture of the colour-field

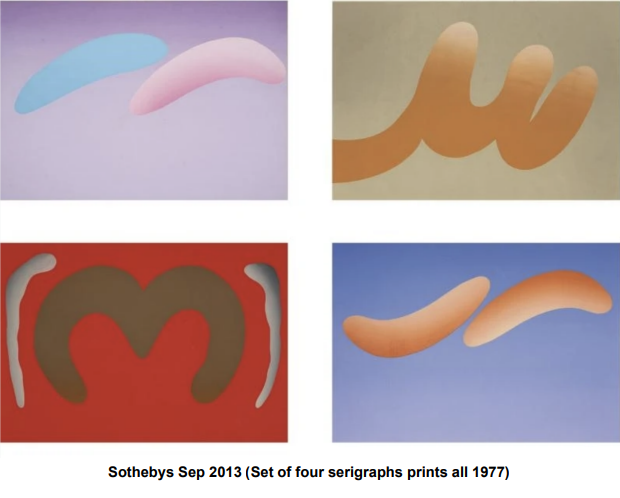

Bawa’s use of colour cannot be separated from his training in printmaking. During his years in England (1967–71), he worked as a serigrapher and printer, developing a discipline grounded in flat planes, calibrated tones, and sharply articulated silhouettes. On returning to India, and later at Bharat Bhavan in Bhopal, he continued to work closely with printmaking studios, producing serigraphs both of his own work and for fellow artists.

This training shaped Bawa’s understanding of pictorial space. The colour-field in his paintings is not a background in the conventional sense; it is a structural plane that holds form in suspension. Bawa’s use of the colour-field also resonates with the Indic concept of akasa—the elemental void or ether that precedes and contains form. Unlike perspectival space, akasa is not recessionary or descriptive; it is an all-encompassing field within which form appears, floats, and dissolves. Bawa’s flat, luminous grounds function in this register: not as atmosphere or backdrop, but as a continuous spatial plane that sustains presence without anchoring it. The figures that later populate his canvases do not occupy space so much as emerge within it.

As Ranbir Kaleka observed from close quarters, Bawa deliberately built these grounds through a methodical process: painting “two layers of the same colour” so that a soft glow emerged, from which “animals and other protagonists seemed to magically emerge, conjured up from this gentle sheen of colour field.” [2] The logic is consistent: the field is established first; the figure must negotiate its presence within it.

The 1977 abstract canvas makes this logic explicit. With no protagonist to anchor attention, the colour-field asserts itself as an active spatial agent, against which the floating form tests its balance.

Abstraction with image-association

The late 1970s represent a transitional phase in Bawa’s practice, in which forms hover between abstraction and figuration. This moment—where form loosens its commitment to anatomy without abandoning bodily reference—was widely noted by contemporary critics. As Geeta Kapur observed, “Manjit paints great expanses of colour with forms that are non-representational but with certain image associations—rubbery limbs for most part—left floating in a fluorescent colour.” [3] These forms resist pure geometry. They suggest bodily presence without committing to anatomy.

Swaminathan similarly located this phase as a necessary passage:

His earlier figurative work, gave place to abstraction where pneumatic forms- both erotic and horrific-floated in a void of mauves, pinks and greens. This phase has now been negated, and the synthesis has resulted in breathtaking poetry. Here animals, plants and humans all cohabit, taking their birth from the same ethereal tissue, like balloons blown into various shapes, engaged in a purposive play which defies understanding. [4]

The abstraction of the 1977 canvas belongs precisely to this chromatic and spatial world. It is not an importation of international modernist abstraction, but a personal invention moving toward Bawa’s distinctive figural idiom.

The curve as principle

Bawa repeatedly articulated his aversion to the hard edge. “I don’t like sharp corners and straight lines,”[5] he told Ranbir Kaleka, noting that even the flute in his paintings resists linearity, bending instead into a continuous curve.

This position—anti-cubist in both impulse and outcome—is not rhetorical; it is embodied in the structure of his forms. As Kaleka observes, Bawa consistently favoured cylindrical, rounded contours, rejecting angular construction in favour of pliancy and flow.

In the 1977 canvas, this principle appears in its most distilled state. The free-floating form exists without iconographic obligation. Curve precedes character; contour precedes narrative. The painting captures the moment before form hardens into identity.

The fingernail: reconstruction of the body from its smallest unit

By the late 1960s, Bawa began to question the gravitational solidity of the body itself. Early charcoal drawings made during his years in London still anchor the figure firmly to the ground. The transition toward weightlessness that defines his mature work was not intuitive; it required a deliberate rethinking of form at its most elemental level.

Bawa described this shift as a process of reconstruction rather than refinement. “The entire body had to be constructed anew,” [5] he explained, beginning not with the torso or limb, but with the smallest component of the body: the fingernail. From this minute unit, he worked outward, testing curvature, balance, and proportion through repeated drawing and printmaking.

Numerous silkscreen prints explore variations of the fingernail, isolating it as a generative form. On small pads and scraps of paper, Bawa developed entire figures from this point of origin, shading rounded limbs with pencil or ballpoint pen. The modest scale permitted constant revision. Corrections were made by overdrawing rather than erasing: a finger bent by millimetres, an elbow softened, a limb subtly rebalanced. In some large canvases, traces of these pencil corrections remain visible beneath the paint layer, registering the persistence of drawing within the finished image.

This method is decisive for understanding the 1977 abstract canvas. The free-floating form is not an arbitrary abstraction; it is the enlargement of a generative unit refined through repetition, correction, and scale. What appears abstract at the level of the canvas is, in fact, the macro-expression of a micro-logic—one developed through drawing and printmaking long before it resolves into figuration.

Sotheby's June 2019, MANJIT BAWA, Untitled (Woman)

Sotheby's June 2019, MANJIT BAWA, Untitled (Woman)

Balance, suspension, and form

The question of balance—formal and existential—runs through Bawa’s work. “Our life is about being suspended in spatial areas… Life is like that to me,” [5] he remarked, framing suspension not as a stylistic choice but as a condition of being.

This philosophy finds concrete expression in the studio. Ranbir Kaleka recalls mornings where music filled the space as Bawa drew, while his son Ravi—unable to hear—responded through bodily vibration. Kaleka links Ravi’s gradual learning of balance to Bawa’s stylisation of the figure: bodies split, counterweighted, poised in precarious equilibrium.

“It is a precarious balance,” Kaleka writes, “arrived at without the supporting skeletal frame, where the split halves of the body seek to counterbalance each other in balletic gestures.” [5]

From abstract unit to populated void

By the early 1980s, Bawa’s language clarifies. As Susan Bean notes, “Bawa fulfilled an ambition he set for himself… he created his own figural form, distinct from the work of other artists. Drawing and plein-air sketching were central to this project.” [6] The colour-field becomes purer and more luminous, and the invented form resolves into recognisable human and animal presences.

Later projects, including the extensive Bagh drawings, extend this logic across an expanded field where humans, animals, plants, and landscape share morphological affinities. Hair, drapery, limbs, foliage, and animal forms echo one another through shared curvature. The abstraction of the 1977 canvas thus reads not as a detour, but as the seed from which this interconnected world unfolds.

Why the 1977 canvas matters

The significance of the 1977 abstract canvas does not rest solely on rarity, though its position within Manjit Bawa’s recorded canvas practice is unusual. Its importance lies in what it reveals about formation. According to currently available market records, including the Artprice database, the 1977 work appears among the earliest documented paintings by Bawa executed on canvas and is distinctive within his recorded oeuvre for its fully abstract treatment. While several silkscreen works on paper from the same year explore related non-representational forms, abstraction on canvas remains rare within Bawa’s known practice.

What the painting ultimately exposes is not an exception, but a foundation: the grammar before mythology, the unit before narrative, the curve before character.

In isolating the free-floating form, the work allows a clearer understanding of how Bawa arrived at one of the most distinctive figural languages in modern Indian painting—one rooted not in anatomical distortion or expressive gesture, but in the slow, obsessive reconstruction of the body from its smallest part outward.

References

[1] M. Bawa, ‘I Cannot Live By Your Memories, Manjit Bawa in Conversation with Ina Puri’, Let’s Paint the Sky Red: Manjit Bawa, Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, 2011, p. 47

[2] R. Kaleka, artist’s recollection, in Let’s Paint the Sky Red: Manjit Bawa, Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, 2011.

[3] G. Kapur, “Manjit Bawa,” in Midnight to the Boom: Indian Modernism, Vadehra Art Gallery / Penguin India, New Delhi, 2013.

[4] J. Swaminathan, quoted in S. Kalidas, Let’s Paint the Sky Red: Manjit Bawa, Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, 2011, p. 17.

[5] Ranbir Kaleka, “Manjit Bawa” (artist’s recollections), in Manjit Bawa: Kala Bagh, Vadehra Art Gallery, New Delhi, 2022.

[6] Susan Bean, “Manjit Bawa,” Midnight to the Boom, p. 128