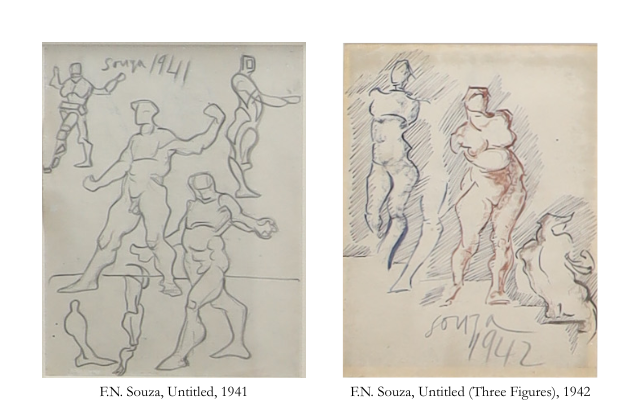

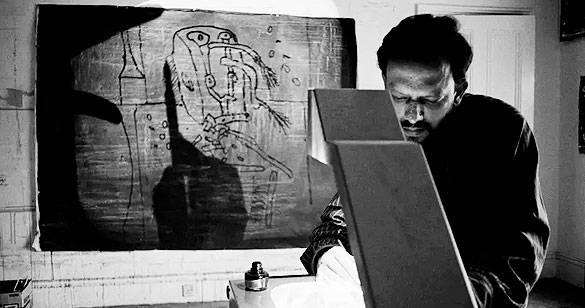

F.N. Souza’s fascination with the human body began early—his expulsion from school in 1939 for drawing explicit anatomical sketches hinted at an obsession that deepened over time. Even in the 1940s, his clinically labeled studies dissected the body with scientific precision, mapping muscles and bones in a relentless exploration of form.

Apart from knowing Perrad (Victor Perrad’s classic book of Anatomy) backwards, I had done Duva, Arthur Thomson, Bridgeman, and a dozen other books of anatomy.. I also did some dissection on superficial muscles on cadavers.

(F.N. Souza, Souza in the ‘Forties, Dhoomimal Catalogue, 1983)

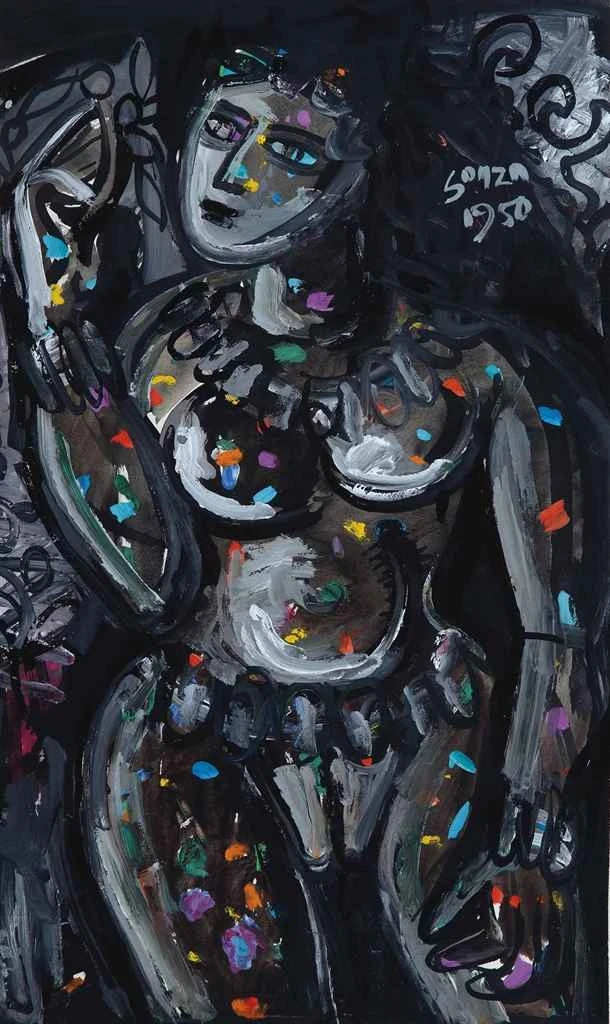

F.N Souza, Untitled (Temple Dancer), 1950, Gouache on Paper

Yet, Souza’s exploration of the human form extended far beyond anatomy. The first works of art that inspired Souza were the South Indian bronzes and the high relief carvings on the Khajuraho temples, both of which he saw reproduced in books in the Bombay library. (Souza by Edwin Mullins, 1962) In 1948, he traveled to Delhi to view an exhibition of Indian antiquities and classical art. There, he was especially drawn to the sublime eroticism of these sculptures, an influence that would resurface throughout his work.

Those mighty temples and pillars and many a carved figure of girls wearing nothing but smiles more enigmatic than even Mona Lisa could manage.

(F.N. Souza, Illustrated Weekly of India, 1960)

F.N. Souza, Untitled (Khajuraho Series), 1949

A key motif in Souza’s engagement with Indian temple sculptures was the Mithuna—the embracing couple—found in the erotic carvings of Khajuraho and South Indian bronzes. For Souza, these sculptures embodied an eroticism “incomparably more sensitive and pure,” as art critic Edwin Mullins observed. Yet, his bold reinterpretations often met resistance. In 1949, two of his works inspired by the Mithuna couples of the Khajuraho sculptural complex were removed from an exhibition at the Art Society of India, deemed obscene. Souza’s exploration of the Mithuna blurred the sacred and the profane, entwining devotion with desire, and faith with flesh—an unbroken thread woven across decades and mediums.

.jpg)

F.N. Souza, Untitled (Temple Lovers/Mithuna), 1984

.jpg)

Installation view of F.N. Souza’s Mithuna / Temple Lovers (1984), shown alongside preparatory drawings and sculptural references, from F.N. Souza: A Continuum.

Souza’s 1984 painting Mithuna/Temple Lovers is a striking reinterpretation of a 12th-century Mithuna relief from Puri, Odisha—now lost to time. His figures, with their exaggerated curves and rhythmic movement, echo the fluidity of Tribhanga, the graceful three-bend stance seen in Indian temple sculpture.

Reference Image: 12th-century Mithuna Relief, Puri, Odisha

This photograph, annotated by F.N. Souza, was a key reference for his 1984 oil painting. Sourced from The Art of Tantra (1973) by Philip Rawson, it captures a lost temple sculpture depicting a celestial couple. Souza’s handwritten note identifies it as a “Couple from the ‘Heaven Band’ of a temple at Puri, Orissa – 12th century.” His annotation signals his deep engagement with classical Indian art, reinterpreting its sensuality and rhythmic movement through his distinct visual language.

Tracing the Past: Souza’s Study for Mithuna, 1984

In this transparency sketch, Souza traces the outline of a 12th-century Mithuna relief from Puri, Odisha, as reproduced in The Art of Tantra (1973). This transparency was placed on a projector, and the outline was used to create the work on canvas. Stripping the image to its essential forms, he captures the fluidity and sensuality of the original sculpture while setting the stage for his final 1984 oil painting.

Souza tracing the outline of the projected reference image of the sculpture Rawson’s The Art of Tantra

Auguste Rodin, The Kiss, 1882

Executed just before the East-West Encounter exhibition in Mumbai (1985), Souza’s Mithuna/Temple Lovers (1984) reflects his engagement with both Indian and European artistic traditions. Auguste Rodin’s The Kiss—a Western masterpiece—finds an unexpected counterpart in Souza’s raw, reimagined Mithuna.

How much Souza's pictures derive from Western art and how much from the hieratic temple traditions of his country, I cannot say… because he straddles several traditions but serves none.

John Berger