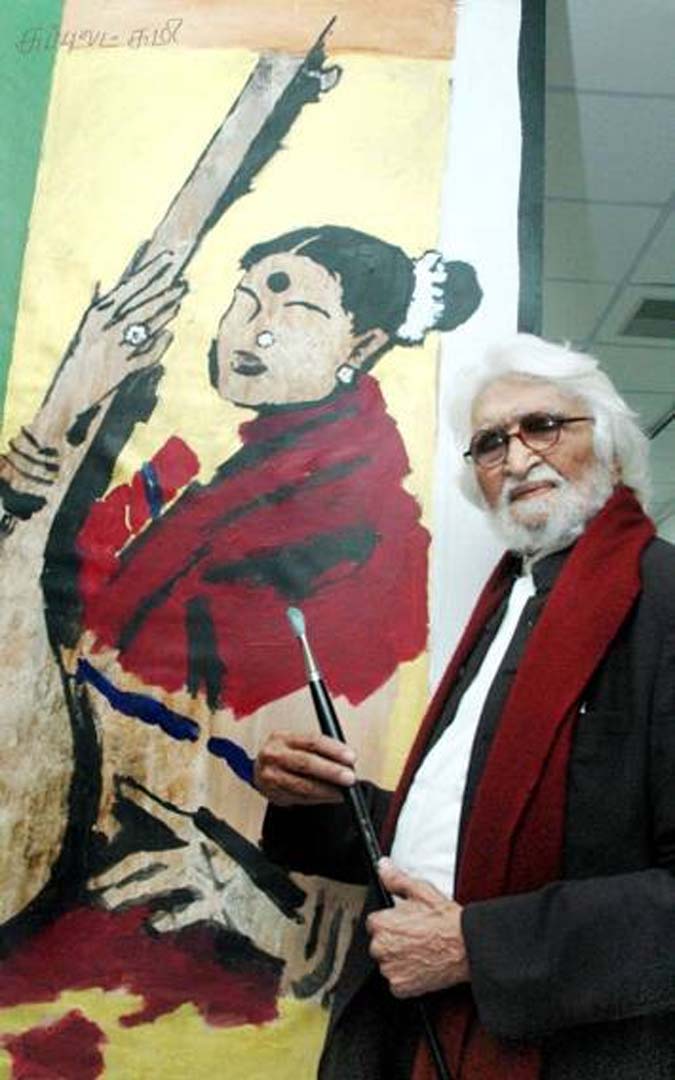

The only time I have seen M. F. Husain in person was at his exhibition in honour of singer M. S. Subbulakshmi at a gallery in Chennai (Madras) in 2004. Wearing no footwear, except for thick black socks, and wielding a massive paintbrush in one hand, Husain was surrounded by a group of Chennai’s socialites. I was patiently waiting behind them to meet Husain when he suddenly popped out and said, “Hello”. I was giddy with excitement and asked him to autograph the invitation card I had in my hand. He did so and quickly moved on to greet the next visitor. Husain was as excited to meet unknown gallery visitors as they were to meet him—the energy was amazing for a man who, at that time, was 91 years old. A year or so later, Husain left India, never to return.

M.F. Husain standing in front of his painting of M. S. Subbulakshmi at Lakshana Art Gallery, Chennai. Image Courtesy of The Hindu Images

While I never had the opportunity to gather biographical knowledge directly from the artist, I have had the fortune of engaging intimately with his artworks as a buyer, curator, and art historian. Accessing primary information on Husain, particularly about his earliest years as an artist, was a daunting task. To separate verifiable facts from myths, urban legends, and fantastical stories about Husain, through a career span of over 70 years, took a lot of time. Peeling back these layers revealed a very interesting origin story about Husain that lends a fresh perspective to understand this ‘Untitled (King of Hearts)’ painting from 1950. [Fig.1] The title ‘King of Hearts’ is one that I have given this Untitled painting–for reasons I will explain through this essay.

Fig 1. M. F. Husain, Untitled (King of Hearts), Oil On Canvas, 1950.

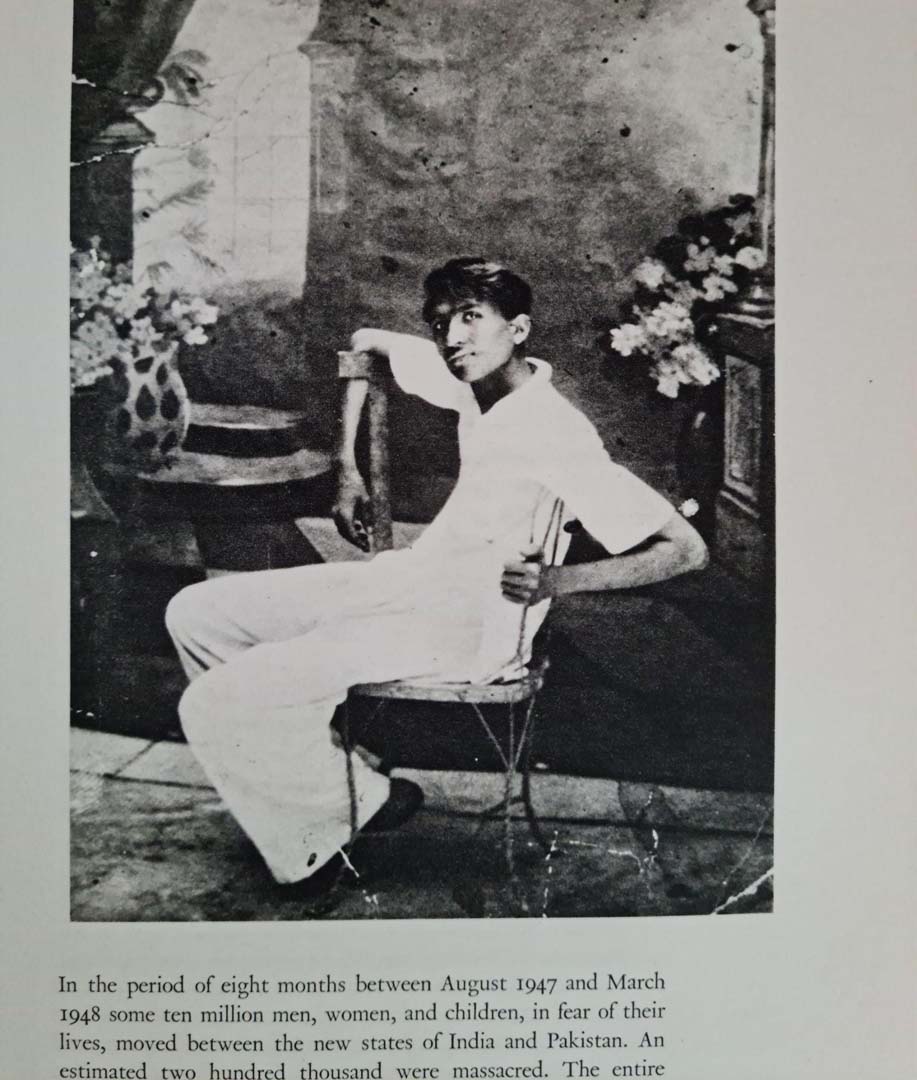

[1] M. F. Husain was born in 1913 at Pandharpur, located in the south of present-day Maharashtra and very close to what was then referred to as the Nizam’s Territories or the Deccan. Husain’s mother died when he was two years old [2] and his father remarried and moved the family to Indore. Husain had an inherent talent to paint and draw and managed to convince his father to financially support his art classes at the School of Art in Indore. Based on the annual report published in 1934-35 by Sir J.J. School of Art, Bombay (the governing academic board for all art schools in the Bombay Presidency including Indore) we learn that Husain completed his Intermediate Drawing Grade examination and even won a prize in the category of ‘memory drawing’. This enabled him to enroll as a full-time student at the same school and in 1936 Husain completed his Intermediate Drawing and Painting level examination. Husain had to travel to Bombay to take these final examinations.

M.F. Husain, age 21, sitting in front of a studio backdrop he had painted. Image Reproduced from HUSAIN. Husain, Maqbul Fida & Richard Bartholomew & Shiv S. Kapur

Establishing the significance of the School of Art, Indore, in the context of Husain and the overall impact it had on the development of Indian Modern Art is important at this point. Dattatray Damodar Deolalikar founded an artists training institute in Indore called Chitrakala Mahavidyalaya in 1927. [3] Shortly after, Yashwant Rao Holkar II, the Maharaja of Indore, provided a building to Deolalikar and it formally became the School of Art, Indore. [Fig.2] [4]

Fig 2. The School of Art, Indore, is today known as the Devlalikar Kala Veethika and is used as an exhibition space. The present Devlalikar Fine Arts Institute, run by the government, functions in a new building behind this one. Image Courtesy: Change.org.

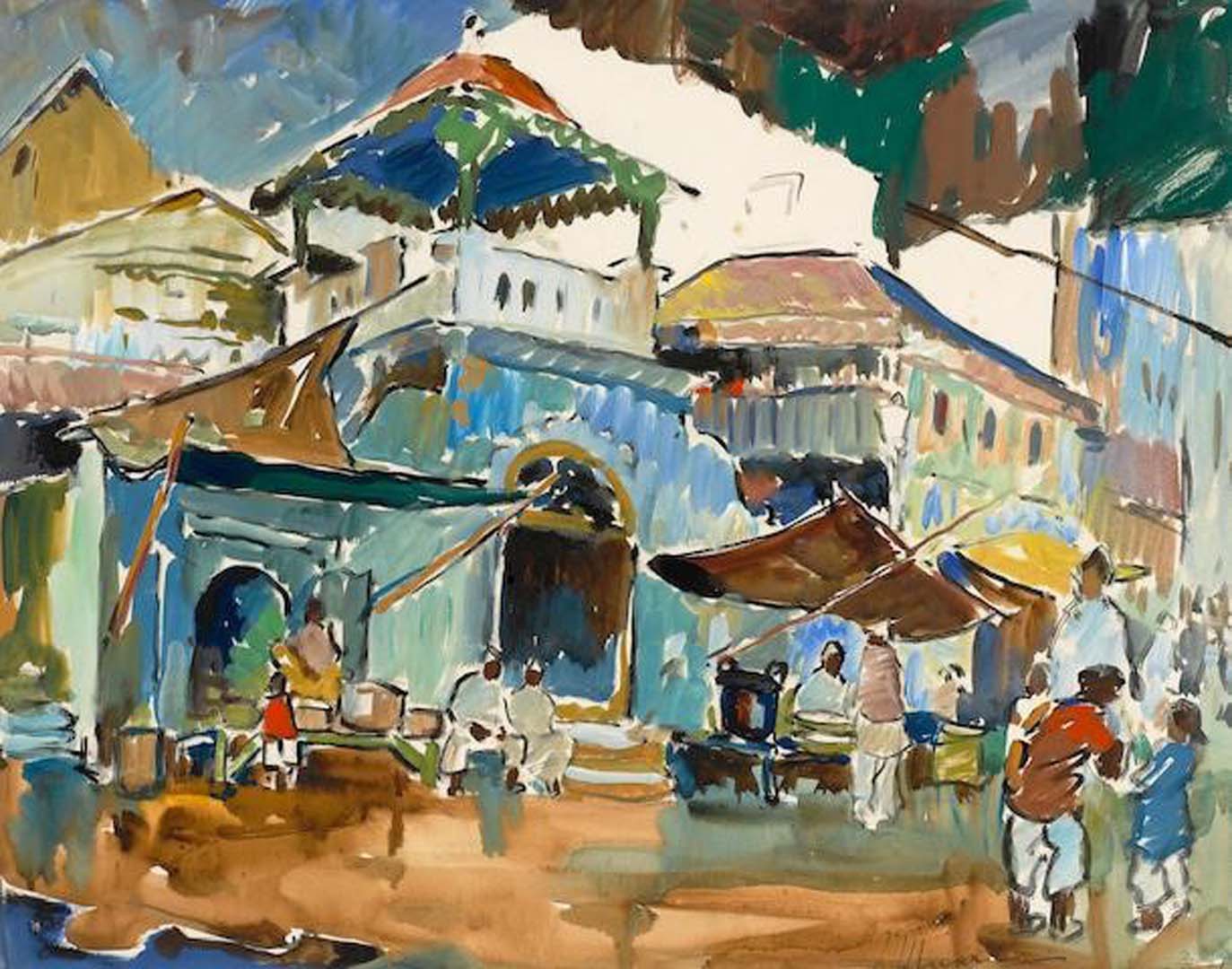

Deolalikar graduated from Holkar College, Indore, with a degree in Sanskrit and then decided to follow his passion for art. So he attended Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay where he learned various techniques including the ‘open-air’ style of painting. The ‘open-air school’ had its origins in the British academic style of painting that was being practiced in Bombay at the turn of the 20th century. Besides teaching his students the foundations of art, it was this ‘open-air’ style that Deolalikar taught at his institute. Some of Deolalikar’s early students such as G.M. Solegaonkar, M.S. Josi, N.S. Bendre, Vishnu Chinchalkar, and D.J. Joshi embraced this style and pushed the boundaries further. [Figs. 16-19] The key features of this Indore version were the use of bright colours, elimination of detail, broad brush strokes, and a sense of sunlight created through the use of contrasting colours that gave an effect of light and shadow–almost photographic in the way the light was captured. Deolalikar would frequently take his students on tours to popular locations near Indore such as Omkareshwar and Dhar to paint in open-air spaces. He would also travel with them to Bombay where they had to complete their annual examinations at Sir. J. J. School of Art—a system that continued till 1965. [5]

After completing a few initial grades at Indore, it was the practice of artists who wanted to follow a full-time career in art, to finish their diploma at Sir J.J. School of Art in Bombay. As students and after graduation, these young artists who studied at Indore and then Bombay would regularly submit their artworks to the Bombay Art Society and the Art Society of India exhibitions that took place annually. Through most of the 1930s and ’40s, the Indore artists won top awards including gold medals and the Governor’s prizes. This Indore style of painting became very popular in Bombay among critics, patrons, and art collectors who were partial to the western school of expressionism and modern art. This style also lent itself easily to artists who were exploring western ideas as a path towards making modern art. The transfer of this style of painting from Bombay to Indore, where it was modified and then re-introduced into the narrative of modernist explorations in Bombay during the ’40s, is what drove the next generation of artists to take a brave plunge into creating a new language for post-independence Indian Modern Art. [6]

A series of misfortunes had cut short Husain’s art education at Indore and he was forced to take up odd jobs to support his father’s large family. While most scholarship on Husain states that he was self-taught, this evidently isn't true. His small but significant stint at the School of Art, Indore, had contributed immensely to setting a foundation for his future career. A small watercolour [Fig.3] of Husain’s children painted in 1947 is an exemplar of his days at Indore and provides a glimpse into Husain’s strong academic skill.

Fig. 3 M. F. Husain, Untitled Portraits, Watercolour on Paper, 1947. Image Courtesy of Pundole’s

Although Husain’s formal education in art was disrupted, it did not deter him from following his ambition to become an artist. Bombay being the metropolis that it was, familiar since the days of Husain’s art school at Indore and filled with opportunities, would have been the natural choice for him to go there and try his luck to find employment to tide over his financial stress. In 1937, Husain moved to Bombay and joined a cinema poster painting workshop “with a meager start of six annas a day”. [7] By 1941, Husain was married and due to this, he needed a steady income and so found work as a designer/painter at a company that made children's toys and furniture. [Fig. 4-5] For some reason it is Husain’s stint as a poster/billboard painter that has been ingrained in the popular imagination. I suppose the storyline transitions better from a struggling billboard artist to India’s most famous and successful modern artist when we picture him this way. Certainly, the story of a furniture designer with a steady paycheck turned artist isn't as glamorous an origin story!

Fig. 4 M. F. Husain, 1941, Watercolour and Pencil on Paper, Image Courtesy of SaffronArt.

Fig. 5 M. F. Husain, Prince Charming, 1944, Pen, and Pencil on Paper, Image Courtesy of SaffronArt.

Before I continue further it would be good to review the various styles of art Husain was influenced by and was practicing till this point in the 1940s. This will help us understand how he approached modern art in the years to come. To make it easier, I am breaking it down into the following points:

- A.

Husain received a foundation-level art education at Indore which gave him a basic set of skills that were dexterous enough to be deployed based on the tasks at hand. He would have learned to draw and paint with watercolours proficiently. The legacy and influence of the Indore School’s technique and their popularity in Bombay would have driven Husain to pursue a similar artistic path to make his entry into the Bombay art scene.

- B.

Husain’s employment as a commercial artist, designer, and billboard painter, for the first 9 - 10 years after moving to Bombay, gave him a completely different approach to making art. The skillset and methods of execution needed for these jobs were different from that of a fine artist. His furniture design relied heavily on precision/industrial drawing to define forms while the colour palette remained muted. The visual appearance of these works was a blend between architectural renderings and, the extremely popular, Walt Disney-inspired cartoons. [Fig.6]

Fig. 6 Detail of a furniture suite designed by M.F. Husain, inspired by Walt Disney characters from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs. M. F. Husain, 1943, Watercolour and Pencil on Board, Image Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

Regarding Husain’s billboard painting career, as there are no known examples, I can only hypothesize the impact this practice would have had on the artworks he went on to create as fine art. Based on the technique used by billboard painters even today, it would have been all about speedy execution and the use of ‘cut-color patches’ to create almost photographic/graphic form, volume, and light. Since these billboards had a very short lifespan, the customers would pay very little for them, which meant that the artists would have to work with very minimal materials yet provide the mass appeal needed to promote movies or products.

So when attempting to understand a work of fine art painted by Husain in this period, it can be theorized that a combination of the Indore painter's palette and its fluid style along with the bright colors and flattened application of paint used to paint billboards, would have been the approach Husain took while making his artworks.

- C.

Husain not attending Sir J.J. School of Art after settling in Bombay also had an impact on how he approached fine art. Had he attended the college, he would have been under the tutelage of teachers like J.M. Ahivasi who were propagating the ‘revivalist’ style. Simply explained, this was a style of painting that encouraged the subject to have a nationalistic narrative which was executed through the combined visual and compositional influences of traditional miniature paintings and the murals at Ajanta & Ellora. In essence, this school of painting was in stylistic opposition to what was being practiced by the Indore artists. The ‘revivalist’ style tended to be more Indian while the Indore style was more Western. Almost all of Husain’s contemporaries including V.S. Gaitonde, A.A. Rauba, B. Prabha, Bhanu Rajopadhye [Figs. 20-23] among many others had to negotiate their way out of this revivalist influence to arrive at their independent exploration of Modern Art in the years to come. Therefore, Husain’s exploration of nationalistic narratives in his artwork, at the peak of the Indian independence movement, took a different approach as compared to his contemporaries. This means that the work we are trying to analyze in this essay was arrived at through an independent approach by Husain.

D.

In the 1940s, possibly even after 1947, Husain was working on a personal project at his employer’s workshop. He was making toys out of plywood cut-outs [Fig. 7] in themes that were from his younger days in Indore—images that represented rural domesticity. These toys were quite colourful and compositionally employed geometric patterns while retaining a wonderful sense of movement and animation. The subject of these toys interestingly retains their inquiry for several decades in Husain’s practice.

Fig. 7 A toy that depicts a horse similar to the one seen in the ‘King of Hearts’ painting. Image Courtesy of SaffronArt.

Keeping this breakdown of Husain in mind, we can move forward to understand how he would have arrived at the ‘King of Hearts’. But before that, a few more things happened in Husain’s career that had a significant impact on his artworks.

iii.

For any artist who wanted to take on the art world in Bombay in the mid 20th century, the first step was to submit their artworks to the Bombay Art Society and hope to be selected by the illustrious committee to exhibit at the annual exhibition at Sir Cowasjee Jehangir Hall. There were several categories for submitting works based on qualification, skill level, and style of painting. In all probability, Husain would have submitted his works under the ‘Indian painting’ category. He would have done this at some point towards the end of 1946 because his works were exhibited for the first time in January 1947 at the 56th annual exhibition of Bombay Art Society. It was only in 1947, at the dawn of India’s independence and possibly after Husain’s financial conditions were stable, that he made a complete shift towards exploring modernism.

It is here at this exhibition that Husain was identified by Francis Newton (Souza) [8] Francis Newton was quite impressed by what he saw and decided to enlist Husain as his inductee into the Progressive Artist’s Group (PAG)—a group for young artists united by a common goal, founded by Francis Newton, K.H. Ara, and S.H. Raza, to explore the progressive and Western modernist ideas in art. While the PAG was established in 1947, Husain only officially joined and started to work with them in 1948.

Looking for images of paintings from the 1947 exhibition I only could find the one reproduced in Husain’s most important publications, titled Kumhar [Fig 8].

Fig. 8 Detail of Kumhar by M.F. Husain. M. F. Husain, 1947, Oil on Canvas. Image Reproduced from HUSAIN. Husain, Maqbul Fida & Richard Bartholomew & Shiv S. Kapur.

I started incessantly searching for more early works by Husain to see if I could find any that were similar to what he might have submitted to the Bombay Art Society’s exhibition in 1947. I came across a set of 5 artworks that were on auction in a Bonham’s 2007 catalogue.

I was thrilled with the discovery because it was for the first time that I had come across works of Husain’s from the 1940s before he joined the Progressive Artist’s Group and that was not his commercial/design work.

Three of these works [Fig.9-11] are particularly important because they have all the makings of the Indore School influence and in tune with the theme of paintings that were popular at the Bombay Art Society and other competitive exhibitions. Their style and execution were very similar to works done by S.R. Raza, N.S. Bendre and a whole host of others at the time.

Reading the auction notes, I realized that these lots however were withdrawn from the auction and there could have been many reasons for the same. After thinking about them for a while, my line of thought generated three possible outcomes. First, the lot was withdrawn because of a breach of the contract either by the seller or buyer. Second, the works were identified before the sale as fake, however, I am fairly certain that these are original because of the stylistic similarities as well as the rock-solid provenance the works have. More so, for anyone to make fakes of this period of Husain’s works had to have seen other works similar to this of which there are none. Third, the artist himself could have objected to the sale of works from a period where he did not want them to enter his narrative; a similar case when S.H. Raza also refused to authenticate early commercial / commissioned watercolours from the ’40s as his works of fine art. Either way, I believe these works to be authentic and they help to deepen our understanding of Husain’s early career. As for the provenance of these three paintings, they were bought by an ex-pat, Norman Alexander Gordon Neil, stationed in Bombay in the 1940s and early ’50s, from an exhibition of Husain’s works in 1951 in Bombay. These five paintings up for auction were among several other artworks of Husain bought by this gentleman at the same time. In a few instances, I have now observed that artists tend to quickly dismiss works from their early career. Perhaps it has to do with bad memories of difficult times or it reveals an uncomfortable truth or it is a point of departure which the artist does not relate to anymore. In Husain’s case, this discovery is a wonderful missing link.

Fig. 9 M. F. Husain, Market Stall, 1947, Watercolour on Paper, Image Courtesy of Bonham’s.

Fig. 10 M. F. Husain, Market Barrow, 1948, Watercolour on Paper, Image Courtesy of Bonham’s.

Fig. 11 M. F. Husain, Street Market, 1948, Watercolour on Paper, Image Courtesy of Bonham’s.

1948 was a year of exploration for the artists of PAG. Newton was organizing a few student shows at the Bombay Art Society Salon, Raza travelled to Kashmir as part of the political movement there, and only towards the end of the year did Husain take a significant step towards realizing his artistic vision. Husain and Newton travelled to Delhi to see an exhibition of classical works that highlighted the best of Indian art from various museum collections across India. This exhibition was a moment of great realization for both of them. It is after this trip that Husain’s engagement and exploration of modern art really found a footing. He now knew that he needed to bring his engagement with the everyday life of people around him to the foreground to highlight his identity and inquiry with his nation.

1949 was the year that the PAG had their first group exhibition of the founding six members. Husain’s works were primarily on canvas at this point and he had moved on to painting with Oils. This was a fairly bold step because the usage of Oils on canvas to paint in a modernist style was a direct break from the tradition of painting academically in this medium-it was in tune with the western idea of Modern Art.

1950 was an interesting year for the entire Progressive Artist’s Group. On February 3rd 1950, Mr. Emanuel Schlesinger, an art collector, inaugurated M. F. Husain’s first solo painting exhibition at the Bombay Art Society Salon on Rampart Row. In April 1950, Chetana, a cafe situated on Rampart Row, decided that it wanted to create a ‘permanent space in the city for artists to exhibit their works and for art-lovers to enjoy the art. A major exhibition was mounted by the PAG at Chetana and it was inaugurated by the Governor and his wife Rani Maharaj Singh on 23rd April. This was not officially a PAG member’s exhibition but included a lot of their peers and guides like N. S. Bendre, Shivax Chavda, Palsikar and Pai among others. On August 10th, the PAG members held another exhibition at Chetana and it is possible that it was at this showing that the painting in discussion was sold.

Looking at artworks from 1950 that Husain made, a process starts to emerge. From the very beginning of his explorations, he was engaged with the common man doing day-to-day tasks. Husain was in the thick of the moment of political independence for India but he seemed to be observing people and tasks that spoke of a certain lack of freedom. Starting from the work Kumhar that shows a potter making pots, his toys of rural domesticity and his large canvases showing daily lives of the underprivileged in the streets of Bombay, Husain had found his footing.

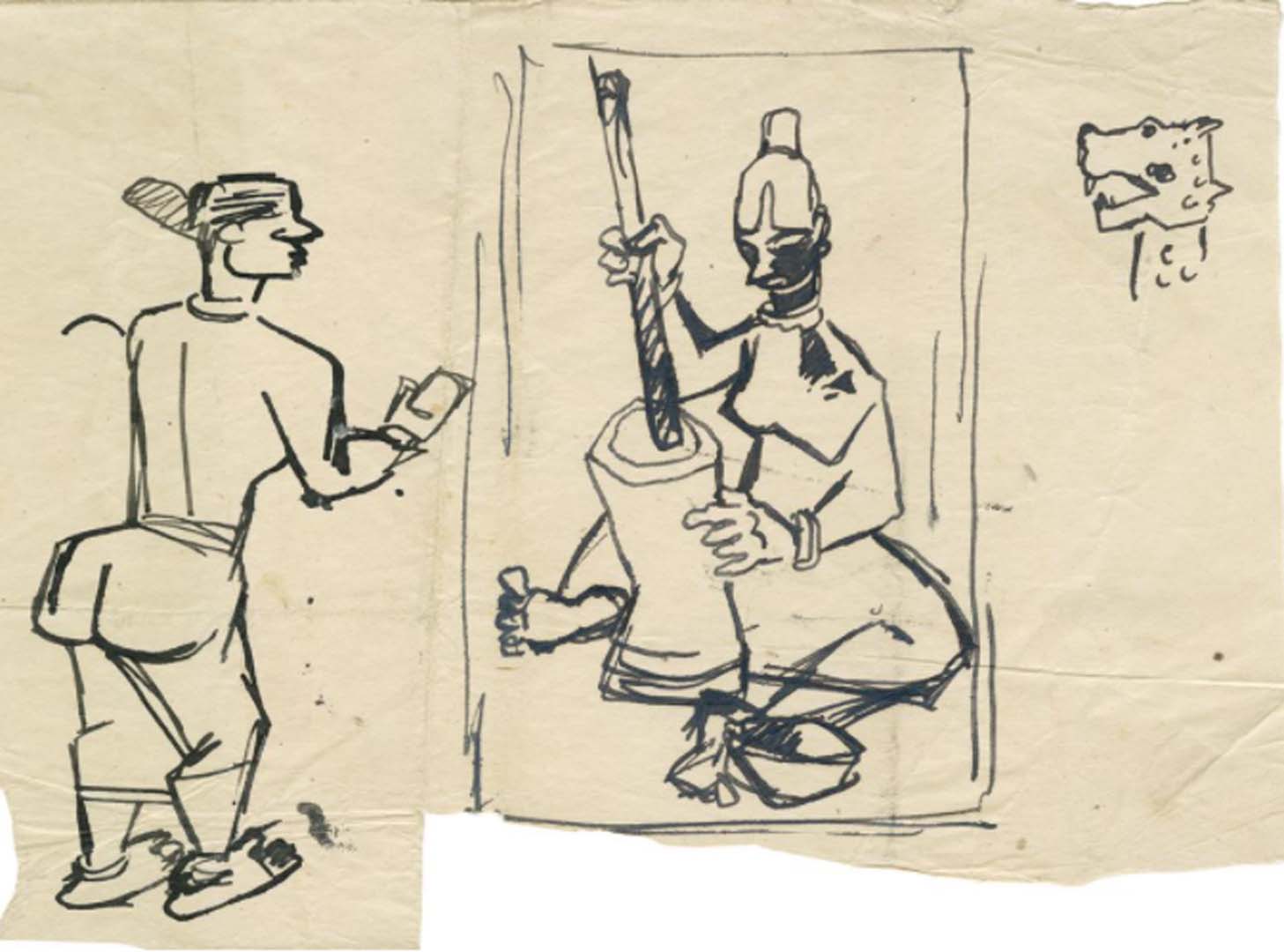

While researching hundreds of archival images of Husain’s works from 1950 to study them in detail, I made some interesting discoveries. Thanks to the wonders of the Internet, all auction houses have their image resources online and I did not have to sit with hundreds of books searching page after page. The discovery was made at a Pundole’s auction dedicated to M. F. Husain in which there were assorted sketches sold that at one point belonged to Husain’s singular most important collector, Badrivishal Pitti. These sketches looked familiar and in no time I was able to match them to their painted canvas versions.

I never realized that Husain was first making sketches [Fig. 12-15] and then working at his studio to paint. This is very different from how Raza, Ara and Gade worked.

Fig. 12 Preparatory sketch for Peasant Couple. Image Courtesy of Pundole’s

Fig. 13 M. F. Husain. Peasant Couple, 1950. Oil on canvas. Image Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum, Salem, MA. Photography by Walter Silver

Fig. 14 Preparatory sketch for Woman. Image Courtesy of Pundole’s

.jpg)

Fig. 15 M. F. Husain. Woman, 1950. Oil on canvas. Image Courtesy of Christie’s.

Looking at these works from 1950, one now starts to understand the construct of ‘King of Hearts’. The picture has everything in it. From geometric structuring of the toys, the cut-color patches of the billboards, and most importantly the central figures of the King, Queen, and their son Jack. The elephant and the horse have always been symbols of royalty and power. The heart clearly represents passion and playfulness. But Husain's painting of a pack of cards represents his careful choice of depicting the common city dweller’s habit of simple entertainment and perhaps their (or his own) gamble of fortune. It is for this complexity of thought and the ability of Husain to connect with his viewer that I called this essay the King of Hearts—Husain was an expert at knowing what his audience wanted.

Mulk Raj Anand sums it up perfectly in his review of Husain’s first publication in 1955 “I would like to suggest that in the work of M. F. Husain, since the years when he left off painting commercial posters, through the hard years of experimentation until now, there has been a more or less sustained effort to create an art of high pressure from within the depth of his Indian psyche, through his Indian experience, and in a new Indian idiom. This is not to deny that Husain has not borrowed almost his whole way of handling paint on canvas from Europe. But he has tried to submit the technical lessons of the West to his peculiarly earthy vision of India.” [9] And when you interpret it this way, Husain truly is the King of Indian Hearts.

M.F. Husain painting in his studio in 1950. Image Reproduced from G. Kapur, Contemporary Indian Artists, 1978.

M.F. Husain painting in his studio in 1950. Image Reproduced from G. Kapur, Contemporary Indian Artists, 1978.

NOTES

1. Based on his birth certificate Husain was born in 1913. However, Husain mentions that he was born in 1915 in a 1951 exhibition catalogue and 1916 is mentioned in a 1950 Progressive Artists Group Catalogue. I chose to go with the official record.

2. Husain, 1951, Exhibition Catalogue, Delhi.

3. Today his institute is called ‘Devlalikar Kala Veethika’ however, records from the 1930s and 40s show that he was referred to as D.D. Deolalikar

4. https://shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in/ Accessed on 18/05/2021

5. http://johnyml.blogspot.com/2009/02/devlalikar-fine-arts-college-indore.html Accessed on 20-05-2-21

6. It is also important to credit the Indore School for this style of painting because of the impact it had on colleagues of Husain like S.H. Raza and H.A. Gade who started their careers with this style, long before their introduction to German Expressionist styles taught to them by European mentors in Bombay in the 1940s

7. Husain, 1951, Exhibition Catalogue, Delhi.

8. Francis Newton started to go by the name of F.N. Souza only from 1949 and therefore I have decided to call him by his name relevant to the period.

9. Books - Paintings of Husain, Anand, Mulk Raj, Marg-art.org

Ashvin E. Rajagopalan is the Director of the Piramal Art Foundation in Mumbai. He has played an integral role in setting up the Piramal Museum of Art alongside being an avid art collector, researcher, and writer.