My earliest memories are swathed in the scent of mountain pines and a constant leitmotif of a rattling train that would carry me back to our home in Dehradun named Mitali on Rajpur Road – my magical El Dorado – where I spent my childhood with my mother, Meera ma, my maternal grandmother, Lal dida, and my Jethu and foster father, Rathindranath (Tagore).

Tobu monay rekho… ‘If tears dim your sight and all play ends one honeyed night, yet remember, yet remember, yet remember…’

Through the first eleven years of my life, with what festivity I had lifted the weight of springtime on my shoulders and scattered a riot of flowers!

Jethu had allotted to me a garden patch in Mitali, our home at 189/A Rajpur Road, and asked me to tend it with care. He had even bought for me miniature gardening tools, replete with a pair of sears and a watering can. And as I had held his finger tightly, he had led me through the nursery, past the shallow lily pool, pointing out the nodding flowers usually associated with an English garden – enchanted blossoms called phlox and larkspurs and hollyhocks and ladies lace and nasturtium and sweet-peas and crocuses and azaleas and narcissi.

Me, ready to go to school in Meera Ma’s Baby Fiat

Mitali – sheltered by the Himalayas in the north and old-fold Shivalik ranges far away, down south. Mitali – a riot of Mary Palmers and crimson hibiscuses and sprawling emerald lawns flanked by flower beds down five cobbled steps abloom with my mother’s special rose bowl. There were roses of all shapes and sizes, from Mandarin tea roses to the stunning magenta of Eden Rose, pink roses bleached by the moon to ashes – ashes of roses – and the golden profusion of the rambling Marshneils.

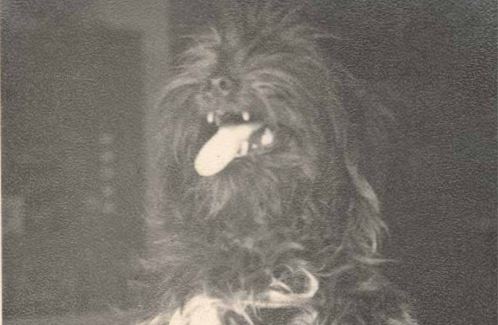

Mitali – ochre complexioned and honeycombed with six large bedrooms, an intimate dining room, and a spacious living room adorned with paintings by Rabindranath, Abanindranath, Gaganendranath, Ju Peon, Nandalal Bose and delicate flora by Jethu himself. A solitary chamber on the roof contained a vast library where I was first introduced to Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer, Charles Dickens’ Oliver Twist, Emily Bronte’s Heathcliff, Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina, Romain Rolland’s Jean Christophe, Agatha Christie’s Miss Marple, Edgar Wallace’s John G. Reeder and several other characters from fiction. There were also two kitchens, garages, servants’ quarters, and a tin shed near the mango and litchi orchards where Shyama-cow and Julie-cow mooed and lowed, and Koeli, the Tibetan terrier, barked her head off. Beyond the shed lay a wire-meshed chicken barn crowded with cackling Leghorns and a solitary Black Menorca rooster that cock-a-doodle-dooed at the crack of dawn and woke Ghanshyam Mali and his assistants with a start. And pervading through the garden was, of course, Jethu’s voice, gently instructing the gardeners – a voice like the deep shade of a tree, foliage-protected, amid a temperate afternoon; a voice so civilized and kind that you were compelled to pay attention to words spoken with equal measure to one and all.

Mitali, my magical El Dorado under construction

Way back in 1906, when he was barely eighteen years old, Jethu was sent by his father, the poet Rabindranath Tagore, to the University of Illinois to study Agriculture. As a college student, he had been instrumental in starting the now famous Cosmopolitan Club. But his interests were always eclectic. My strongest memory is of him bent over a block of wood in the afternoons, his head haloed by the light of a dull electric bulb, either diligently inlaying it with intricate chips of ebony and ivory, or shaping it into a beautiful jewelry box, a pen holder or a coffee table. His joinery was extremely well-equipped. A local carpenter worked along with him, sawing the larger slabs of teak or Sheesham to the sizes Jethu required. Sometimes I would join Bachhan Singh who would let me pare away at a redundant wedge with a miniature saw and shape it into building blocks that I would later color.

On my fifth birthday, my Jethu had built me a wonderful wooden steed – a cross between a rocking horse and a miniature pony – complete with stirrups and a comfortable seat.

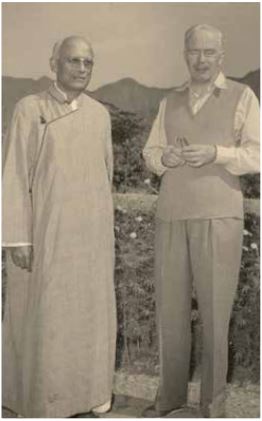

Rathi Jethu with Uncle Leonard (Elmhirst)

He had placed him strategically on springs so that I could ride the foal to my heart’s content without falling off. For a while this charger became the love of my life and only if I was feeling generous would I share it with Bugga, the janitor’s son, and my best friend. Bugga was a snotty-nosed, mischief-laden scallywag but he had endeared himself to the residents of Mitali with his impeccable takeoff on Ravan. Without my mother or Jethu finding out when I was home from boarding school for my Dussehra holidays, I would slip out at night with my ayah, Kanchi Ama, and walk at least two miles guided by Bugga’s sharp whistles and the pale light of a waxing autumn moon to the Ramleela grounds where the local servants metamorphosed into delectable thespians. I too was hell-bent on becoming an actor. So I’d sing my way through most of Balmiki Pratibha exclusively for Jethu’s pleasure. My reward was a set of wonderful wooden swords that he crafted for me and the next time we came to Calcutta, Bhola-babu, who was the manager at Jorasanko, was instructed by Jethu to buy me a dacoit’s costume, complete with a pair of false mustachios, and take me to see the Great Russian Circus. On rain-filled evenings he would sit me on his lap, play his Esraj at Guha Ghor in Santiniketan, gently running the bow on the strings, and teach me to sing songs whose meanings I’m still constantly discovering – Oi ashono toley; Roop shagorey doob diyechhi; Amaarey tumi oshesh korechho and Kholo kholo dwaar.

With family friends at Mitali in Dehra Dun

Winter holidays in Calcutta never concluded without dinner with Ma and Jethu at Skyroom on Park Street or Nanking in China Town, and a special Sunday lunch at the Firpos on Chowringhee. My table manners – taught to me at Mitali – came in handy. It was Jethu who showed me the difference between a fish knife and a carving knife, between a salad plate and a quarter plate, a pastry fork and a regular fork; he showed me how to use the various items of the Mappin & Webb silver cutlery that had been arranged at the table and insisted that I washed and wore clean clothes for dinner, ate my soup without slurping and consumed the rest of the repast with my mouth closed and a napkin spread on my lap. Lunch at home was typically Bengali, consisting of the usual rice, dal, shukto, and fish or meat curry. But dinner, sharp at 7.30 pm, was always European, served with a flourish, item by item, by Jethu’s valets, Bahadur and Sundru, at the formal dining room on Royal Doulton crockery or a beautifully handcrafted Paris Pottery dinner service. It was a pleasure to see Jethu peel an apple at breakfast with a great ceremony. The artistry of the act was almost Zen-like, now that I look back. Every meal shared with him was an art. He loved his eggs sunny side up if they were fried, with just a pat of butter on his toast. Or the cook, Janak Thakur, would make us the most delectable scrambled eggs.

Jethu often had visitors who stayed back for meals. During my childhood, it was very fashionable to host tea parties and Jethu had inducted Ma into sipping the most fragrant of Darjeeling teas – the delicately-scented Flowery Orange Pekoe. He was also a wonderful cook and often baked me a cake for my birthday. Some evenings, he would walk into the kitchen and stir up a mean Shepherd’s Pie and a fluffy mango soufflé. And when the orchards in Mitali had a surplus of Guavas, he would make the best Guava jelly that I have ever tasted. Our table at home was always generous. And a variety of invitees came to dinner – from house guests like Uncle Leonard (Leonard Elmhirst), Pankaj Mullick and Suchitra Mitra, the legendary musicians, to scientist Satyen Bose on his way to Mussoorie, Pandit Nehru who often visited Dehra, Lady Ranu, and Buri Mashi and Krishna Mesho (Nandita and Krishna Kripalani).

Memories of Mitali

I clearly remember the performance of a play, Pathan, by the larger-than-life thespian Prithviraj Kapoor and his troupe who had come to Dehra Dun. Jethu was invited to the show as Chief Guest, and Ma and I had accompanied him. The next evening the players were invited to dinner at home. In the cast were Sati Mashi (whose daughter Ruma-di was then married to Kishore Kumar) and the very young and dashing Shammi and Shashi Kapoor who turned many feminine heads at the reception! But the startlingly Falstaffian Prithviraj-ji, affectionately known as Papaji, insisted on sitting at Jethu’s feet throughout the evening, much to Jethu’s embarrassment. He just wouldn’t budge and kept saying, ‘How can I have the arrogance to sit next to Gurudev Rabindranath’s son?’ He dragged me by my hand and had me sit on his lap, ruffling my hair as he talked to other guests.

Meera Ma

Jethu and Ma had formed a cultural organization – Rabindra Samsad – and many plays and dance dramas by Gurudev were performed by its members. Ma was a veteran actress, having played Rani Sudarshana in Arupratan and Rani Lokeshwari in Natir Puja, directed by Rabindranath in Santiniketan. So watching Jethu direct her in Bashikaran, Lokkhir Porikhha and Chirokumar Sabha was, for me, a treat. Ma also directed Natir Puja, Ritu Ranga, Bhanushingher Padavali, and a children’s play, Tak-duma-dum, scripted by Jethu’s aunt, Jnanadanandini Debi, where I played the lead as the wily jackal! Rabindra Samsad also held regular musical soirees. I can never forget Jethu’s excitement as I debuted as a soloist when I was barely seven. He was on tenterhooks, restlessly pacing the wings, while I sang blissfully to a packed hall, unaware of a live orchestra that accompanied me. Rabindra Samsad often screened interesting Bengali films. My introduction to Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali and Debi happened in faraway Dehra’s Prabhat Cinema.

Rathi Jethu with Nripen Mitra, his solicitor and friend, Ami dada, Meera Ma and me

Jethu was also an ardent painter and spent long hours at his easel, working on beautiful water-colored landscapes and delicate flower studies. Watching him paint was fascinating as he brought to life a clump of dense bamboos, the hills in the distance, delicate poppies glimpsed through a window or pale frangipani arranged in a vase. Sometimes Ma painted along with him and also crafted many items via the complicated art of batik.

One of Jethu’s favorite hobbies was blending and making perfumes that were later filled into the most delicate glass-blown bottles. He’d gift Ma different fragrances on her birthdays. And many a morning would be spent combining the scents and concentrates of flowers like roses, Juhi, and mogra that came all the way from Ujjain. He’d leave no stone unturned till he got the aroma right, pulling away at his cigarette – he smoked either Three Castles or John Peel or Abdulla Imperial – sometimes forgetting to tip the ash into a generous steel ashtray that always lay on his side table. His scent bottles became coveted possessions for all those who were lucky enough to receive them. Usually, after the Rabindra Samsad shows, there would be lively cast parties at Mitali, and the actors and singers waited with baited breaths till Jethu gave them a bottle of perfume as a parting present.

Meera Ma

Around my Jethu, light-footed and non-intrusive, an innate appreciation of aesthetics kept vigil. His impeccable sense of color, interior decor, landscaping, and gardening lent to his persona tremendous elegance. The last ten years of his life and the first ten years of mine were, for both of us, absolutely gilded and filled with the fragrance of the golden champaka blossoms that he loved so dearly. But when he died, the aroma – stripped of its enchantment – slowly vanished. Mitali could never be the same again without its kind and gentle prince, my beloved foster father, who had loved me unconditionally and opened up before my eyes splendid vistas of art and music and literature, reading to me poems from Shishu written by his father or magnificent stories from Raj Kahini crafted by his cousin, Abanindranath, when the weather turned cold and we sat by the fireside, watching the flames leap and softly die.

Koeli, Rathi Jethu’s favourite Tibetan terrier

Yet, as I write today, shadows turn to songs. The mist lifts and the rainbow arches over the mountains again, drifting back for a moment the enchantment that was my childhood spent in my Jethu’s benign shadow. Past the wounds of words, the sun appears once more, spilling henna on the soft palms of peaceful mornings. And in the many-splendors story of my Ma, Baba, and Jethu I re-live the most civilized, glorious, and compassionate friendship that I will ever care to remember.

- Jayabrato Chatterjee