Like a blithe child colouring on the walls despite protests, nothing deterred F.N. Souza (b. 1924) from asserting his art. His art, whose first impact is to shock, elicits a childlike element of uninhibited honesty with no filter, unafraid, and almost oblivious to those offended. His unrestrained and thought-provoking body of work makes one wonder about the power of art and its hold over the human psyche. Broad and bold lines jump out of the canvas attacking with speed, deeming him an eternal rebel.

I have made my art a metabolism. I express myself freely in paint to exist. I paint what I want, what I like, what I feel. When I begin to paint I am wrapped in myself, rapt; unaware of chromium cars and décolleté dillentantes, wrapped like a fetus in the womb only aware that each painting for me is either a milestone or a tombstone... I do not unwrap myself when I paint. I unwrap myself when I write. When I press a tube I coil. Every brush stroke makes me recoil like a snake struck with a stick. I hate the smell of paint. Painting for me is not beautiful. [1]

The Artistic Journey of FN Souza: Early life

Born in Goa, Newton Souza lost his father three months after his birth and his sister a year later. The grief and sickness that followed painted in his mind a bleak picture of the world in which he lived. Souza and his mother Lilia moved from Goa to Bombay where he contracted smallpox and was sent back to live with his grandmother. His childhood was immersed in nature and Konkani Catholic practice in Goa. The influence of Catholicism on F.N. Souza remained profound - he was fascinated by the Church's grandeur and tales of tortured saints narrated by his grandmother. This also sparked Souza's obsession with painting heads throughout his artistic oeuvre; portraying religious figures in a grotesque fashion. He continued to paint various heads in the 1950s and 1960s in line with his gamut of figurative art.

After his recovery, Souza went back to Bombay to his religious mother who had prayed to Goa’s patron St Francis Xavier to cure her son in return for him becoming a priest. She then added Francis to her son's name and enrolled him in St. Francis Xavier's College. Souza, however, had other plans for himself.

The rigid curriculum at the college stifled the rebellious Souza. "The system was only good to turn Indians into toddies," Souza said. However, he did develop an interest in drawing and studying oleographs and prints. He was expelled two years later for drawing offensive images in the lavatory. Souza defended himself saying that he hated bad drawings and was merely correcting them.

The 1940s

The decade of the 1940s was particularly important in shaping Souza's artistic oeuvre. In 1940, 16-year-old Souza joined the JJ School of Art. During this time, he was fascinated by the city he was bred in, Mumbai erstwhile Bombay. It was the sight and sounds of the city that fuelled his imagination rather than any textbook.

"Bombay with its rattling trams, omnibuses, hacks, railways, its forest of telegraph poles and tangle of telephone wires, its flutter of newspapers, its haggling coolies, its numberless dirty restaurants run by Iranis, its blustering officials and stupid policeman, its millions of clerks working clockwise in fixed routines, its schools that turn out boys into clerks in a mechanical, Macaulian educational system, its bania hoarders, its women carrying tiffins to the clerks at their offices during lunch hour, its lepers and beggars, its paan wallas and red beetle nut expectorations on the streets and walls. Its stinking urinals and filthy gullies, its sickening venereal diseased brothels, its corrupted municipality, its Hindu colony, and Muslim colony and Parsi colony, its bug-ridden Goan residential clubs, its reeking, mutilating, and fatal hospitals, its machines, rackets, babbitts, pinions, cogs, pile drivers, dwangs, farads, and din." [2]

The city of contrasts with its high-rise buildings and massive slum dwellings became a fixation and artistic inspiration for Souza. Souza painted the poverty-stricken, labourers, and sex workers, and as a true reflection of his political leanings, the loathed rich whilst giving his works influential titles like The Proletariat of Goa and The Criminal and the Judge are made of the same stuff.

Souza continued his rebellion against authority and establishment at the JJ School. The teachers of JJ at that time followed strict academic guidelines with no desire to explore the avant-garde movements in Europe. Souza's curiosity about art in Europe would lead him to Walter Langhammer's studio (one of the foremost patrons and critics of the Bombay Progressive Artists' Group) every evening on Nepean Sea Road to hear his tales of the European Art scene. This was also when Souza's political passions came to the forefront. In 1942, he joined the Quit India Movement and took part in the mass protests to spark an orderly British withdrawal from India. He was also against the British Principal of JJ at that time and was eventually expelled in 1945 before receiving his diploma for challenging the system. Almost in a fit of rage, Souza set about painting immediately after his dismissal. On the day of his expulsion, he marched back home and narrated the incident to his mother. The expulsion seemed to have sparked something in him. Souza shares the anecdote:

I was 21 years old then. I started painting furiously in oils with a palette knife on a large piece of plywood my mother had bought to use as a cutting tabletop for dressmaking. I painted an azure nude with still life and landscape in the background. I finished the painting in an hour of white heat and titled it The Blue Lady and exhibited it in my first one-man show in December 1945. [3]

“It was an angry, impulsive picture, and in painting it he discovered the way he wanted to paint,” [4] said Edwin Mullins. 50 selected paintings and drawings from a total of a couple of 100 works, all done within six months of Souza's expulsion. Souza then decided to head back to Goa to paint with a more stimulating intensity.

_(1).jpg)

(Goan Village) by F.N.Souza, Gouache on paper, 1948

"In those days, I was painting peasants and rural landscapes. I painted the earth and its tillers with bold strokes, heavily outlining masses of brilliant colours. Peasants in different moods, eating and drinking and toiling in the fields, bathing in a river or a lagoon, climbing palm trees, distilling liquor, assembling in a church, praying or in procession with priests and acolytes. Carrying monstrance, relics, and images; ailing and dying, mourning or merrymaking in market-places and feasting at weddings.” [5]

In Goa, he painted small-format watercolours of Goan landscapes whilst revealing the plight of the down-trodden in India. He also experimented with oil on canvas and board. Souza's childhood obsession with the Church translated into his works in the late 1940s. Souza returned with a portfolio of works to Bombay and his paintings were displayed at the new frame shop on Princess Street ( a primarily Christian Goan area of Bombay) in 1946. His works were not received well by the locals, they said, “ Goan people did not look like that horrible Francis Newton paintings.” Souza's unappreciative surroundings did not dim his creative vigor. These paintings were on their way to the Silverfish Club, New Book Company for Newton’s second one-man show in July 1946. However, just like Souza resisted the establishment; the establishment too resisted him, and the pictures he entered for the Bombay Art Society Annual Exhibition in 1946 were all rejected.

The emergence of the Progressive Artists' Group

In 1947, the country saw Independence, the partition, regional rioting, and death; all of which deeply affected artistic expression. It was in this milieu that F.N. Souza decided to establish the Progressive Artists' Group which was to be a defining movement in Indian Art. Souza conceptualised the formation of a collective. He was based in Bombay at the time, which was itself an important cultural center. The PAG according to Souza was also a protest against the school of thought of the JJ School of Art and the Bombay Art Society. He said:

I had begun to notice that JJ School of Art turned out an awful number of bad artists year after year, and the Bombay Art Society showed awful crap in its Annual Exhibitions…. It then occurred to me to form a group to give ourselves an incentive. Ganging up in a collective ego is stronger than a single ego. It is easier for a mob to carry out a lynching; and in this case, we found it necessary to lynch the kind of art inculcated by the JJ School of Art and exhibited in the Bombay Art Society. [6]

The founding members of the group consisted of F.N. Souza, S. H. Raza, and K. H. Ara. After the invitation of one extra member each, the group included M.F. Husain, H.A. Gade, and Sadanand Bakre. As per Souza, the artistic endeavour of the group was to create new art for a newly free India. Souza was given the job of secretary, Gade treasurer, Ara PR, and Raza was given the task of drawing new clients to their exhibitions. Souza was the one to extend the group's invitation to Husain who he first met painting billboards for the Indian film industry. Only after seeing his talent at the Bombay Art Society did he invite Husain to be a part of the group.

The Progressives would often travel to various places to expand their artistic knowledge. Husain and Souza visited the India Independence Exhibition in Delhi and were fascinated by the Khajuraho sculptures on display. Classical Indian Art and the Khajuraho with erotic carvings of temple performers were some of Souza's muses which were often spotted in his works.

Souza's paintings from 1947 hint toward his Communist leaning. Where most of his works revealed the plight of the downtrodden, sending out a strong political statement. Souza soon received an award at the Bombay Art Society Exhibition and also married Maria Figuerido in 1947. Maria would continue to be one of Souza's biggest supporters and promoters of the PAG.

.jpg)

The Progressive Artists' Group, Bombay, 1949. Front row: F.N. Souza, K.H. Ara, and H.A. Gade, Back row: M.F. Husain, S.K. Bakre and S.H. Raza

After holding various informal exhibitions in Bombay, the first defining PAG exhibition was held in 1949 at the Bombay Art Society Salon in July. It was around this period that F.N. Souza decided to use Souza as his last name as a result of not wanting to be confused with the mathematician Newton. These works were devoid of Souza's political leanings, unlike his earlier works. He eventually left the Communist Party saying:

I left the Communist Party because they told me to paint in this way and that. I was estranged from many cliques who wanted me to paint what would please them. I don’t believe that a true artist paints for coteries or proletariats. I believe with all my soul that he paints solely for himself. [7]

The second show followed in Calcutta in 1950. The interaction between the Calcutta Group of Bengal and the PAG artists played a role in holding this joint exhibition. The last group show of the PAG was held in 1953. By this time new members had been associated for the purpose of exhibitions, which included Krishen Khanna, Gaitonde, and Akbar Padamsee. It also included the only woman member of the PAG- Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya.

The group formally disbanded in 1956. One of the key factors for this is that three of the artists moved abroad. Souza and Bakre departed for London, whereas Raza moved to Paris. Husain too began shuttling between Mumbai and Delhi.

The public eye

In 1948, Souza held his third solo show at the Bombay Art Society and his fourth show later that year in November. Souza wore many hats and would often write manifestos, introductions to his own catalogues, and essays and give memorable interviews. He was an artist with a conquer over both the pen and paintbrush. He wrote in his fourth exhibition catalogue:

“I underwent an abortive art training. The teachers were incompetent. I was expelled from the School of Art. I was banished from a secondary school. Shelley was expelled once, Van Gogh was expelled once. Ostrovsky was expelled once. Palme Dutt was expelled once. I was expelled twice. Recalcitrant boys like me had to be dismissed by principals and directors of educational institutions who instinctively feared we would topple their apple-carts.” [8]

The Times of India reviewed this exhibition saying that no criticism could take away from the artist’s steadily-growing talent which seemed singularly out of place in its unappreciative surroundings. The following year in 1949, he exhibited at the Art Society of India at the Sir Cowasji Jehangir Hall in Bombay. Two out of the four works he submitted were inspired by the ancient classical sculpture. Though initially approved for exhibition, these works were taken down four days later on the grounds of censorship. Souza's studio was then raided and he was charged with obscenity.

London calling

Souza was exhausted from having no artistic liberties and wished to no longer live in an environment where his art was not allowed to thrive. Be it the stringent establishments or the activities of the police, Souza wished to elope with his art to a universe more accepting of his creative spirit. He decided to move to London to exercise his artistic potential and freedom to the fullest. Even more so after written encouragement from his artist friend Ebrahim Alkazi who moved to London two years previously. Before leaving the country, Souze decided to hold one last exhibition of his works to gather funds for his trip. The exhibit was indeed a demonstration of Souza's artistic evolution. In 1949, 26-year-old Souza embarked on his journey to London. Maria followed suit the following year in spring.

With just £15 in the pocket of his only suit, Souza's immediate needs were paint and brushes, food, and a week’s rent. He would write back to the PAG sharing his experience with his artist comrades:

I have started painting. Plywood is impossible to get, all wood is exported. I have bought two sheets of compressed cardboard for which I paid 8 Shillings! More than I paid for the large plywood on which I had painted my self-portrait in Bombay. [9]

Unperturbed by his lack of means to an end in 1949, Souza immersed himself in the art scene of London. He walked from one art gallery to the next, one museum to the other, fascinated after seeing in flesh the artworks he would only read about in books. Souza saw the works of Rembrandt, Picasso and also Amedeo Modigliani. Souza, despite having not a single dime in his pocket when the world was on the brink of a new decade, continued to fight for his art.

The years 1949-54 comprised a great struggle for Souza to achieve recognition in London's artistic and literary circles. Even more so after World War 2 which had stripped London of its reputation as a Bohemian Centre. Souza's works in the early 1950s expressed his fascination with the duality of sin and sensuality in art. His body of work was controversial in the sense that it bound the sacred and the profane together. His rapture with the female form, classical Indian sculpture, and the visual culture of Catholicism were all reflected in his works. However, his early artistic creations failed to grab the attention of galleries and patrons. He then decided to reconnect with his contemporaries S.H. Raza and Akbar Padamsee while travelling to Europe. This was also when he met Picasso for the first time which he later described as a defining moment in his career.

Souza's signature style

.jpg)

UNTITLED (Pope) by F.N. Souza, Oil on Canvas, 1961

Souza's signature style was a coalescence of Western and Eastern techniques and motifs; an artistic language derived from his fascination with temple sculptures, Catholicism, the works of old European masters, African tribal art, and European modernism. Souza's obsession with the visual culture of Catholicism stemmed from his childhood days in Goa. His body of work hence also comprises an array of paintings portraying religious iconography with compelling paintings of Christ. His oeuvre is also notorious for visualisations of erotically charged nudes, distorted human figures, landscapes, self-portraits, human sexuality, and conflicts in a man-woman relationship. His works were not always pleasing to the eyes of the common folk. However, it took Souza six years to establish himself amidst the British. Maria was initially the sole breadwinner of the family while Souza supported himself through occasional exhibitions and his journalism. In 1955, it was Souza's writing and not his art that brought him into the limelight with his autobiographical essay, Nirvana of a Maggot, which was published in Stephen Spender's Encounter magazine. An impressed Spender helped Souza with introductions in the art world.

In 1955, Souza gained immense recognition at Victor Musgrave’s Gallery One; his first solo show held in Britain. Souza had seven solo shows with Gallery One. The following year till the 1960s saw consistent support from an American patron called Harold Kovner. Souza also received great acclaim from key art critics of the time including Edwin Mullins and David Sylvester. This was also the time when Souza developed his black painting series which he described as evidence of his rebellious streak. These works revealed Souza's most favoured subjects apparent only when viewed at certain angles under the light.

.jpg)

UNTITLED (Leaning Nude) by F.N. Souza, Lithograph, 1963

Souza often used black to traverse his favourite themes such as nudes, portraits, religious scenes, and landscapes. His bold works characterised by thick cross-hatching lines.

For me, the all-pervading and crucial themes of the predicament of man are those of religion and sex. [10]

Souza's body of work revealed his constant dwelling on religion, a theme he revisited throughout his oeuvre stemming from his strict Roman Catholic upbringing and his anti-clerical stand on the Church. It also comprised Goan vistas, sex, intimacy, and grotesque heads. A decade of success and patronage followed. While female forms were centric in Souza's artistic oeuvre, the majority of the women he painted after 1953 were European.

"How much Souza’s pictures derive from western art and how much from the hieratic temple traditions of his country, I cannot say. Analysis breaks down and intuition takes over. It is obvious that he is a superb designer and an excellent draughtsman. But I find it quite impossible to assess his work comparatively. Because he straddles several traditions and serves none." [11]

Souza's depiction of heads

UNTILED (Head) by F.N. Souza, 1956

Souza painted numerous grotesque heads in London. These works did not display any kind of resemblance to the traditions of Indian art. He continued painting heads throughout his life, and later in his career, they would become even more mutilated and monstrous than the ones he painted in the 1950s. What was unsettling about these heads, in particular, were the contorted facial features.

I have created a new kind of face [...] I have drawn the physiognomy way beyond Picasso, in completely new terms. And I am still a figurative painter [...] He stumped them and the whole of the western world into a shambles. When you examine the face, the morphology, I am the only artist who has taken it a step further. [12]

Justifying his protagonists having such unique heads and faces, the eccentric artist once said, “Renaissance painters painted men and women making them look like angels. I paint for angels, to show them what men and women really look like.”

The 1960s and later years

In Spring 1960, Souza received a nomination from the British Council to tour Italy and Europe on an Italian Government scholarship. Souza's works from his brief stay in Rome are vibrant and revel in red with explosive energy. The artist was opening up his mind to the cultures of the world and spent several months in Rome developing a body of paintings displayed in another solo show at Gallery One, titled Twenty-seven Paintings from Rome.

Souza also visited his home country for the first time in 11 years, after his initial departure in 1949. Here, he revisited his birthplace in Goa and when in transit pondered over absolute Roman Catholicism in Rome and Goa.

In the late 1960s, after shows and exhibitions in Europe, India, and the United States, Souza decided to move to New York with Barbara Zinkant (his second wife) after his divorce from Maria in 1965. She would give birth to their first son in 1971. This turned out to be a period of dramatic technical experimentation for the artist. Here, he began using brighter colours in a brushy, expressionistic manner with a more joyful palette. He would also paint cityscapes and landscapes as intricate illustrations of his US travels.

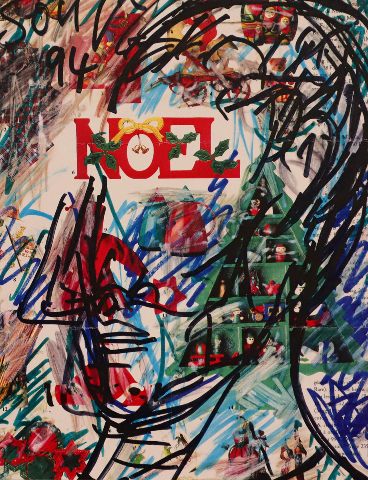

UNTITLED (Portrait) by F.N. Souza, Chemical alteration and ink on paper, 1994

His artistic experimentations included a series of chemical drawings which comprised painting over or drawing figures on torn pages of coloured magazines, catalogues, and printed photographs using chemicals to dissolve the painter's ink. Souza continued travelling extensively and painting in his modest Manhattan studio up until his demise in 2002 while visiting Mumbai.

Souza was an artist reckless and unapologetic in his ways; unperturbed by the responses his art elicited. An artist so fearless in his mode of expression with a blatant disregard for convention, hence crafting his own unique artistic language deeming him the art world's nonpareil even today.

References

[1] F.N. Souza, F.N. Souza - Words and Lines, New Delhi, 1997, p. 10.

[2] F.N. Souza, Nirvana of a Maggot, Words and Lines, Villiers Publications, London 1955, 15 –16

[3] F.N. Souza, ‘The Progressive Artist’s Group’, The Patriot Magazine, Sunday, 8 February 1976, p. 4 & 5.

[4] Edwin Mullins, “F.N. Souza: An Introduction” (1962).

[5] F.N. Souza, Nirvana of a Maggot, Words and Lines, Villiers Publications, London 1955, p. 12

[6] F.N. Souza, “The Progressive Artists’ Group,” Patriot Magazine, 8 February 1984, quoted in Dalmia, 42-43

[7] F.N. Souza, ‘A Fragment of Autobiography’, Words and Lines, Villiers London, 1955, p. 10.

[8] F.N. Souza in the catalogue of his exhibition opened by E. Schlesinger at Bombay Art Society Salon, Mumbai, November 1948, Undocumented.

[9] Ed. A.Vaypeyi, Geysers, Letters Between Sayed Haider Raza & his artist friends, Raza Foundation, p. 11 –15

[10] F.N. Souza, An interview with Mervyn Levy Souza, 1964

[11] John Berger, “An Indian Painter,” The New Statesman, February 26, 1955, 277–78, quoted in Dalmia

[12] F. N. Souza quoted in Y. Dalmia, 'A Passion for the Human Figure', The Making of Modern Indian Art: The Progressives, Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2001, p. 94