Bhanu Athaiya often described herself simply as “a painter who came to cinema.” She carried the discipline of her art training into every film she worked on, treating costume as an extension of character. Actresses who worked with her — from Waheeda Rehman to Zeenat Aman — remembered how she would sit with them, discuss each scene, and ensure that they felt completely at ease. Rekha called her “a mentor, creative guide, and friend,” [1] while Meena Kumari’s first words to her on the set of Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam were, “Bhanu, take care of me.” [2] That instinct — to listen, to understand, and to protect — would come to define her feminist practice.

Bhanu Athaiya was clear about one thing: “To hypothesize or assume what should be done or not done as a woman is not for me to do. I can only speak about my own journey.” [3] Her journey, remarkably, was shaped almost entirely by women — a grandmother who valued education, a mother who raised seven children alone, and a wide, interlinked community of women who recognised her talent at every stage.

“Till today, I am amazed at how at every stage in my life and career, women have influenced me or helped me move ahead,” [3] she wrote in her essay The Role of a Woman in Cinema. This was not a rhetorical line; it was Bhanu’s history — a reminder that her ascent in cinema rested on women who recognised her potential before the system ever did.

Kolhapur: Shaping Sensibilities

Athaiya’s artistic sensibility was shaped in Kolhapur, a princely town with a deep cultural and theatrical tradition. Its folk and classical performances — from Tamasha to devotional plays — placed women at the heart of narrative. Growing up amid these forms, she saw femininity as expressive, not ornamental. Kolhapur’s egalitarian, multicultural environment, its painters, and its early film studios provided her with an understanding that art and design could coexist. That costume could convey emotion as much as image.

Gayatri Sinha writes that Bhanu’s “sensibility was honed and refined in the courtly ethos of pre-independence Kolhapur, and the many layers of cosmopolitan Bombay, where she received her training.” [4] Sinha situates her within “the courtly ethos of pre-independence Kolhapur… under its ruler Shahu Maharaj, [which] came into the forefront of aesthetic and cultural endeavour and produced some of the finest performing and visual artists of the pre-independence era.” [4]

Among the painters Bhanu grew up seeing were Abalal Rahiman and M.V. Dhurandhar, whose works hung in the Kolhapur palace. She later recalled, “one of Abalal’s paintings of a woman going to a temple painted in the realistic manner was a prized possession in my father’s personal collection, and I admired it frequently.” [5] Her father, Annasaheb Rajopadhye, an aesthete and amateur artist, “practised photography and took to filmmaking, an influential medium in Kolhapur from the 1920s.” [5]

This background, as Sinha observes, gave Bhanu “a pan-Indian calling card of ethnicities, histories and politics, all coming together on her drawing board.” [4] The seeds of her feminist vision — seeing women as carriers of culture — were already sown in that world of performance, painting, and experiment.

Lady in Repose: The Artist’s Eye

Bhanu Athaiya, Lady in Repose, 1951, Oil on canvas

Before cinema, Athaiya had already defined her visual language through Lady in Repose, painted at the age of twenty-one. The work earned her the Gold Medal at J. J. School and marked her emergence as an artist of exceptional confidence.

Gayatri Sinha writes that Lady in Repose “broke new ground with the manner in which she made the nude appear to advance and recede between different colour planes. The entire composition was marked with black cross-hatching, which lent it a brooding symbolism. This showed a considerable shift from the Sher-Gil inspired works she had produced in the previous year.” [4]

Art critic Ranjit Hoskote observes that:

...the artist also sets up a netting that protects the nude from our prying gaze. While the protagonist of this painting is confident in her sensuousness, unself-conscious in her pose,‘Lady in Repose’ does not offer itself up for the delectation of the male gaze. If anything, we are made aware of our questionable locus as viewers of a private, even intimate moment. This painting is not the work of an acolyte of male masters. It is, already – the artist was 21 – the work of an artist whose sensibility would be described as feminist today, a woman who knew her mind and would make her way in the world. [6]

Athaiya was also the only woman to exhibit with the Progressive Artists’ Group, alongside M. F. Husain, F. N. Souza, and S. H. Raza, placing her within the same post-Independence modernist current that shaped India’s visual identity.

From Canvas to Costume

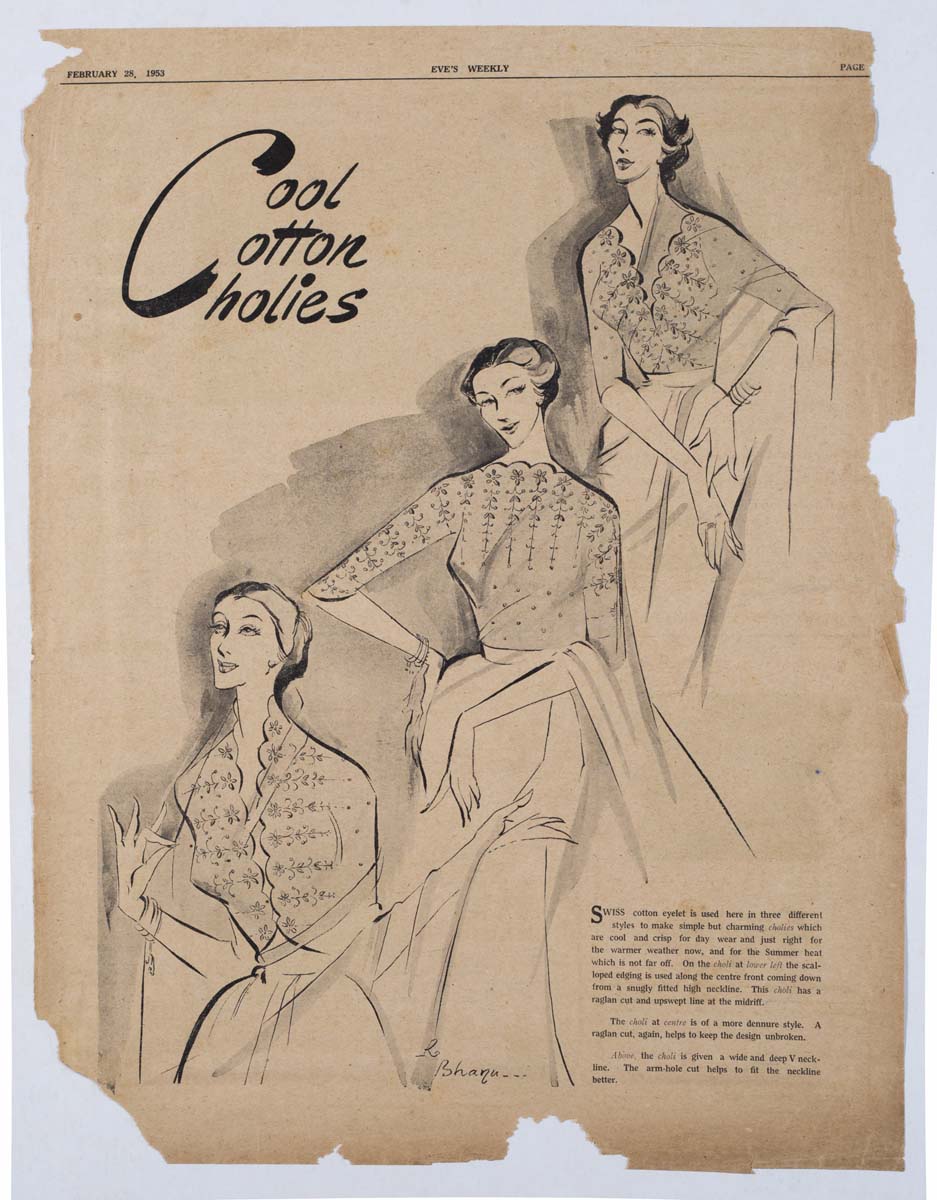

While still a student, Athaiya joined Eve’s Weekly as a fashion illustrator — a rare position for a woman in 1950s Bombay. The magazine became her bridge from art to cinema.

Bhanu Athaiya’s intricate sketches graced the pages of the renowned women’s magazine Eve’s Weekly, which made its debut in the late 1940s. As a versatile fashion illustrator, she unveiled trends that resonated with the modern Indian woman, transforming clothing from a mere necessity into a form of self-expression. Her large-sized fashion illustrations, featured every Saturday across two pages, made her a familiar name in Bombay’s creative circles. This period marked a pivotal turn in her career — she was not only shaping the image of the contemporary Indian woman in print but preparing to translate that sensibility to the screen.

Actors who saw her illustrations approached her to design their on-screen costumes. “The moment the fashion was seen, all the actors also started chasing me, so I didn’t have to go knocking on any doors, people knew who I was. Top directors like Guru Dutt and Raj Kapoor told me to leave fashion, come and do films.” [7]

It was not a departure from art but a change of medium. She began to paint women not on paper, but in fabric, form, and movement — extending her visual philosophy from the canvas to the camera.

Her entry into cinema was not orchestrated through men or industry power brokers — it was propelled by women. Hima Devi, one of the leading personalities in Indian Theatre, gave her a home in Bombay. Meeradevi Chatterjee, Senior Editor of Fashion & Beauty, India's first fashion magazine, spotted her talent and hired her. Kamini Kaushal was the first to commission her for a film. Nargis introduced her to Raj Kapoor. Decades later, Simi Garewal and Dolly Thakore pushed her to accept Gandhi. Across her life, her progression was powered by women who believed in her before the industry did.

Bhanu later reflected on this ecosystem of support in deeply personal terms: “Each of us has some tale to tell… I can only talk about my journey as a woman in cinema, about all the women who inspired me and helped me climb the ladder of success.” [3]

Bhanu’s career moved across an astonishing spectrum of female representation.

The directors ranged from Kumar Shahani, an aesthete who imaged his women with a delicate sensuosity, to Helen, the epitome of the spectacular, dancing on sparkling stilettos with her feathered plumes.[4]

In this span of narratives, she drew on Indian fabrics, regional drapes, and modern silhouettes with equal ease, shaping how the urban middle class saw beauty, glamour, and womanhood on screen. For Bhanu, there was no hierarchy between the stillness of a classical heroine and the velocity of a performer.

From Darji to Designer: A New Language of Costume in Cinema

When Bhanu entered the film industry, costume design itself was barely recognized as a credited profession. For decades, Indian film credits mentioned no designers at all, or buried them in passing acknowledgments. It was only in the 1950s that the first above-the-line credit appeared — to Bhanu herself, credited as Bhanu Mati in Guru Dutt’s Pyaasa (1957).[8]

At that time, most designers were women working far from the studio system. They stitched costumes in their own homes or in tailoring shops, collaborating with dresswalas and independent tailors. Many worked directly for actresses as personal designers, extending the star’s own wardrobe onto the screen. A heroine’s tailor might remain constant even when the designer changed — a reminder that the profession was fluid, informal, and largely invisible.

Bhanu changed that. She brought drawing, research, and artistic authorship into a space that had previously relied on improvisation. Her sketches guided tailors; her references guided directors. What had once been an adjunct to the star system became a visual discipline with its own authority. The shift, as scholars note, marked the moment when “dressmen” stopped being the primary creative negotiators of costume, and designers — many of them women — began shaping cinematic identity.

It is against this landscape that her early work with Nadira, Zeenat, Waheeda, Mumtaz, and Helen must be understood.

Vamps, Modernity, and the Women Who Rewrote the Frame

Nadira— The First Modern Femme Fatale

In the 1950s and early ’60s, Hindi cinema divided its women sharply: the “virtuous heroine,” wrapped in modest silhouettes, and the “modern woman,” whose confidence, clothes, and bearing placed her outside that narrow frame. Into this landscape entered Nadira — born Florence Ezekiel — who would become Hindi cinema’s defining screen vamp, and one of its most striking modern women.

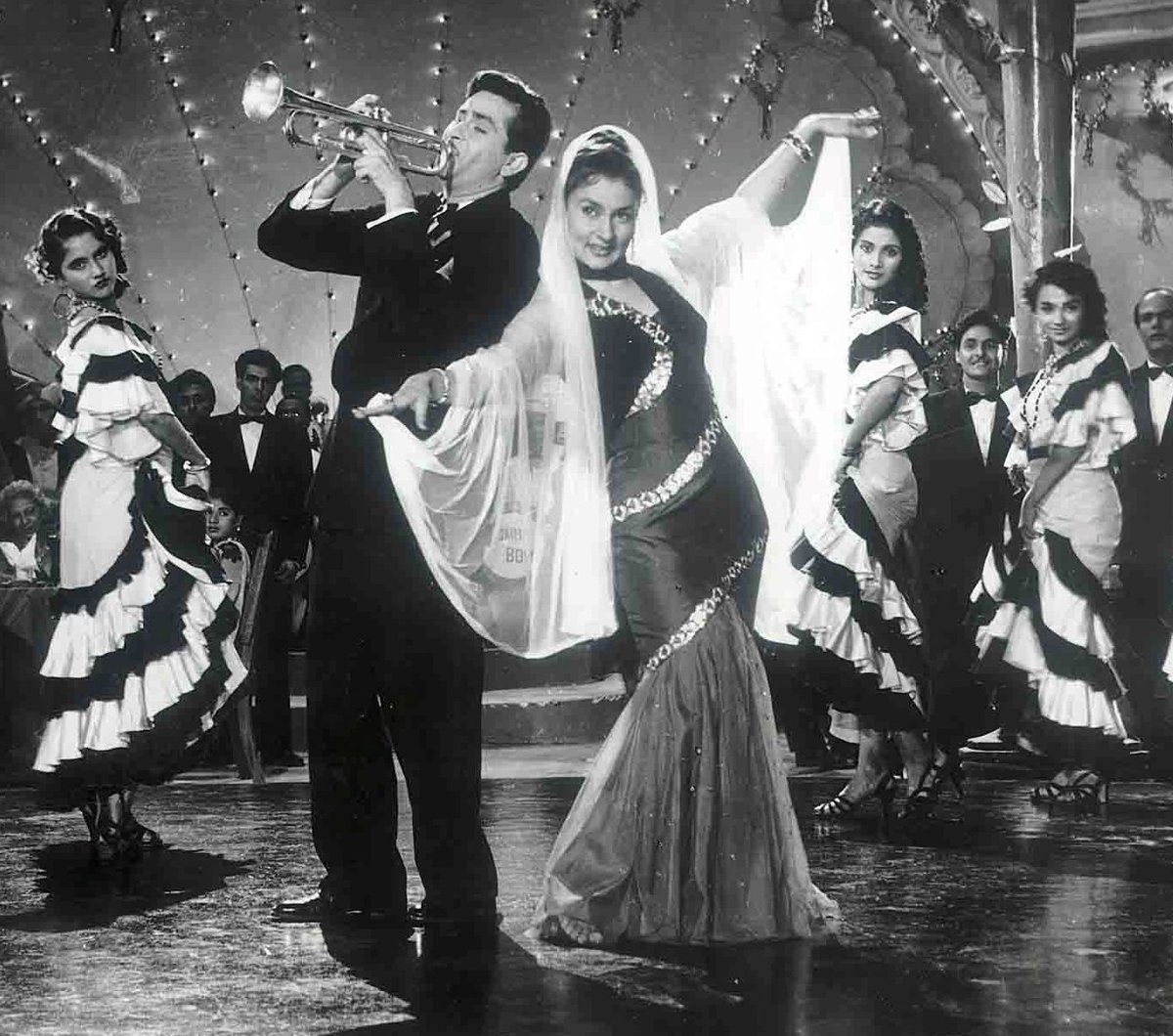

She appeared in over sixty films, yet her influence was larger than her filmography. Her elegance, her stillness, her refusal to soften her edges created a new archetype: the urbane woman who carried herself with composure and confidence. Her breakthrough came with Mehboob Khan’s Aan (1952), one of India’s earliest Technicolor films. The wardrobe — structured, contemporary, sharply defined — signalled a shift in how modernity could be worn on screen. But it was Shree 420 (1955) that made Nadira unforgettable, and it is here that Bhanu Athaiya enters the story.

Nadira in Shree 420 (1955)

Shree 420 was Bhanu’s first assignment for R.K. Films, and she designed solely for Nadira. In the film, Nadira’s fitted gown, cigarette holder in hand, introduced a visual language that Indian audiences had never encountered before. Writing in her book, The Art of Costume Design, Bhanu said:

"I designed a dress for Nadira that showed a bare shoulder, a knotted necklace, adding a twist to the look. The idea was to break the norm." [9]

Nadira in Shree 420 (1955)

Bhanu described the look directly:

In the famous song ‘Mud mud ke na dekh’, Nadira dons a costume with a snake-like border coiling from hemline to neck. [9]

She was not designing shock value. She was designing character — a silhouette that belonged to Maya’s world, not to the industry’s moral binaries. Bhanu disrupted the “good woman / bad woman” divide without announcing it. She made space for a screen presence that was modern without apology, sensual without caricature, assertive without being flattened into a trope. Her work on Nadira became one of the earliest touchstones for what would later be called the femme fatale in Hindi cinema — only here, it was rooted in authorship, not stereotype.

Mumtaz: Modernity With a Wink

By the late 1960s, Hindi cinema’s idea of the “modern woman” was changing. She wasn’t only the nightclub dancer or the vamp; she was also the city-bred woman who worked, travelled, flirted, and carried her confidence without apology. Mumtaz stepped into this changing frame with a charisma that was energetic, intelligent, and wholly her own.

Her rise was built on relentless ambition. She began as a child extra, worked through the stunt-film era with Dara Singh, and often shot two shifts a day. “I was extremely ambitious,”[10] she said later — a drive that shaped everything from her professional choices to her refusal to give up acting after receiving a Kapoor marriage proposal. She wanted a life beyond the pedestal of domesticity.

Mumtaz in Brahmachari (1968)

Bhanu Athaiya entered this story at a moment when Mumtaz was transforming from supporting actor to star. In Brahmachari (1968), Bhanu dressed her in the vivid orange sari with a gold border for “Aaj Kal Tere Mere Pyaar Ke Charche,” a look that instantly became a cultural marker. Mumtaz delighted in colour — “orange is my favourite, I’m a Leo,” [10] she said — and Bhanu translated that brightness into a silhouette that was playful yet elegant. It announced Mumtaz without compromising her ease.

The vivacious and sultry Mumtaz captivated the hearts of the nation with her scintillating dance in this orange-stitched and draped sari in the famous song ‘Aaj Kal Tere mere Pyaar Ke Charche’. It was a departure from the typical Indian sari and I draped it to give her freedom of movement for her dance.[9]

This film was a milestone for Bhanu because Mumtaz’s sparkling persona inspired her to visualise a unique sari-dress for an iconic song number. Bhanu did full justice to Mumtaz’s attractive and free spirit. The lyrics of the song, the mischief in Mumtaz’s eyes, and the dress all came together to create a legend in Hindi commercial cinema.

In Aadmi Aur Insaan (1969), Bhanu refined this language further. The black mesh top and fitted skirt — remembered today as one of Mumtaz’s most modern looks — embodied a quiet paradox: full sleeves, high neckline, and yet unmistakable allure. Mumtaz’s modernity did not rely on exposure; it emerged from confidence, intelligence, and control. She later described Bhanu as “serene, sophisticated, and one of my favourite designers.”

Bhanu explained one of the film’s most discussed looks in her own simple way, “Although the neckline is high and the sleeves are full-length, the style and colours evoke seduction.”[9] It’s the perfect description of Mumtaz’s modernity: elegant, assured, and completely in her control.

Mumtaz and Dharmendra in Aadmi aur Insaan, 1969

Designing Mumtaz meant something different: it meant dressing the everyday modern woman — the one who worked, laughed, flirted, argued, lived. Not a vamp, not a damsel, not a deity — just a woman who didn’t shrink.

Their collaborations — from the playful orange of Brahmachari to the glamour of Aadmi Aur Insaan — helped shape the emergence of an urban heroine who could be funny, ambitious, sensual, and serious in the same breath.

Mumtaz was not performing modernity; she was modernity. Bhanu’s costumes didn’t create that spirit — they honoured it.

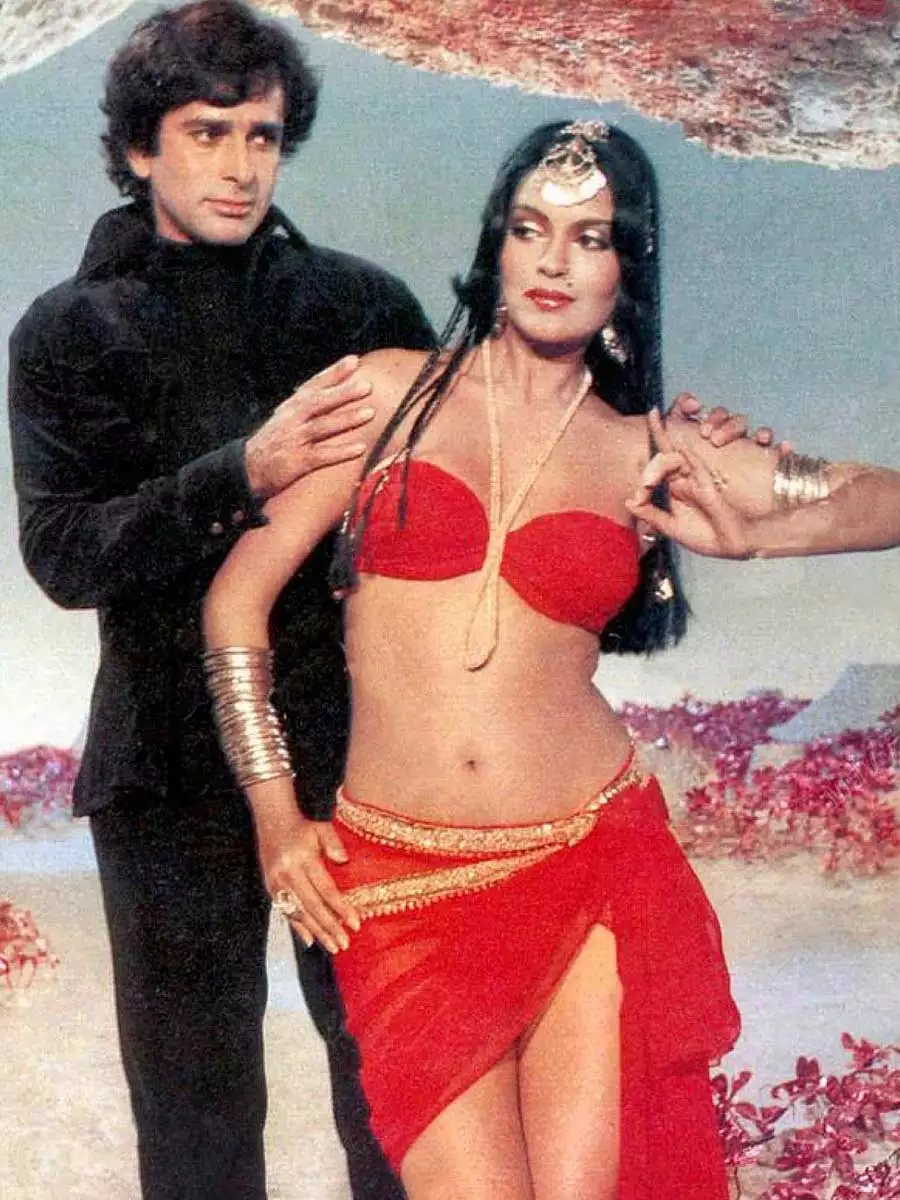

Zeenat Aman — Claiming the Frame

.jpg)

Zeenat Aman in Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978)

By the mid-1970s, Zeenat Aman, like Bhanu, had already unsettled the old split Hindi cinema relied on — the “good heroine” wrapped in virtue and the “bad woman” marked by desire. Her characters flirted, argued, left men, returned to them, changed their minds, and stayed entirely themselves. Producers began writing roles with ambiguity and intelligence — no halos, no cautionary labels.

Satyam Shivam Sundaram is where her story meets Bhanu Athaiya’s feminist vision most clearly, and the way she became Rupa says everything about agency on both sides.

During the shoot of Vakil Babu, Raj Kapoor would spend downtime narrating the story he hoped to make next: a man in love with a woman’s voice who cannot accept her appearance. He spoke about it for days. He never once suggested Zeenat for the part. She knew why — the “modern” image, the minis, the boots. So she decided to cast herself.

One evening, she wrapped early, returned to her van, and dressed as she imagined Rupa: ghagra–choli, parandi, tissue-paper scars glued to her face. Then she walked to “The Cottage” at R.K. Studios, Raj Kapoor’s informal durbar. His aide opened the door. Zeenat said, “Saabji ko kaho ki Rupa aayi hai.” [11] He burst out laughing, delighted and disarmed. Twenty minutes later, Krishna Kapoor arrived with a handful of gold guineas — her signing amount. Rupa was cast not as a muse, not by chance, but by self-definition.

Bhanu enters just after this moment. The role demanded two women held in one body: Rupa, the village woman marked by a scar, and Rupa as the shimmering apparition in the hero’s imagination. Raj Kapoor first imagined the fantasy song as classical dance. Zeenat, who calls herself “no classical dancer by any stretch”, [11] burst into tears when she heard the brief, convinced she would sink the film.

The solution was collaborative. Choreographer Sohanlal taught her mudras instead of complex routines. Art director A. Rangaraj built a surreal world of giant blossoms, smoke, and shifting clouds. And Bhanu designed costumes that could hold their own inside that visual storm — jewel-heavy but never gaudy, sculptural but never stiff, sensual but never cheap.

Zeenat Aman in Satyam Shivam Sundaram (1978)

Zeenat’s only non-negotiable was comfort and dignity. Looking back, she said, “None of my costumes looked crass — especially something made by Bhanu.” [12] Radhika Gupta recalls that her mother felt only Zeenat could have worn those outfits with such ease, “never tugging, never adjusting, just gliding.” [12]

.jpg)

Zeenat Aman as Rupa in Satyam Shivam Sunda

Image Courtesy: Zeenat Aman's Instagram

The now-famous J.P. Singhal photographs belong to this chapter too — shot at R.K. Studios during a look test in Bhanu’s costumes. Raj Kapoor, still unsure whether audiences would accept Zeenat in this avatar, cut a short reel set to “Jaago Mohan Pyare” and screened it for distributors.

This picture was taken by photographer J P Singhal during a look test for Satyam Shivam Sundaram around 1977. We shot the series at RK Studios, and my costumes were designed by Oscar-winner Bhanu Athaiya.[11]

After the first screening, the rights for every territory sold immediately. The “controversy” around Rupa’s sensuality began there and never quite left the film. Zeenat, for her part, has always been amused rather than defensive:

"I do not find anything obscene about the human body… The set is not a sensual space. Rupa’s sensuality was not the crux of the plot, but a part of it. Every move is choreographed, rehearsed, and performed in front of dozens of crew members." [11]

Her clarity is precisely why her collaboration with Bhanu matters to this essay: Bhanu did not design “boldness” — she designed presence. Autonomy. The right to occupy the frame without apology.

The Mannequin: A Feminist Artefact

The deep trust between them is clearest in Zeenat’s own remembrance from her Instagram post:

I’ve been blessed by the hand of many a genius… The formidably talented Bhanu Athaiya designed my costumes for over 15 movies, including Satyam Shivam Sundaram. She was prolific and meticulous, and soon after our first partnership had a mannequin made to my measurements. It would stand in her studio, and on this inanimate bust she would actualise the fantastical ideas that appeared in her mind. I only had to pop in occasionally for trials — an arrangement most suitable to my schedule. No other designer created outfits that were as comfortable as they were sensual.[11]

The mannequin becomes a quiet symbol of Bhanu’s feminist practice — a body-double that allowed her to craft sensuality in privacy, without repeated fittings, without scrutiny, without the exhaustion actresses were often subjected to. Comfort wasn’t an extra; it was the first principle.

A partnership across fifteen films

Their partnership began in Dhund (1973) — a quiet thriller where Bhanu dressed Zeenat in soft saris. It was the beginning of a working rhythm built on trust: conversations, not sketches; silhouettes shaped around the character’s emotional temperature, not around spectacle.

By Hum Kisise Kum Naheen (1977), that trust had deepened. Zeenat’s single qawwali appearance is remembered today for a different reason: Rishi Kapoor sitting on not one but two cushions so he wouldn’t appear shorter than her. Beneath the humour was Bhanu’s early mastery of Western silhouettes on a Hindi-film star — a freedom she often said Zeenat alone allowed her.

Shalimar (1978) shifted the tone entirely: crisp whites, nurse uniforms, a controlled austerity that still held elegance. By then, Bhanu could modulate Zeenat’s presence with the smallest inflection of line and fabric.

Zeenat Aman in Shalimar (1978)

With Ali Baba Aur 40 Chor (1980) — the Indo-Soviet production — the palette exploded. Bhanu travelled through Central Asia for research, returning with turbans, veils, jewellery, and fabrics that Zeenat used almost like props. Radhika Gupta recalls her mother’s delight watching Zeenat wrap, lift, and play with a veil without ever disturbing the silhouette.

In Qurbani (1980), the collaboration entered a different register. The Australian Broadcasting Commission capture of Zeenat on set — rehearsing “Laila O Laila,” speaking candidly about wage disparity — shows a star fully aware of the contradictions of her time. Behind the glamour was the same precision: Bhanu’s costumes that moved cleanly with Feroz Khan’s kinetic camera, even on days when he famously docked Zeenat’s pay for arriving late. The clothes held the confidence; the partnership held the professionalism.

In Insaf Ka Tarazu (1980), Bhanu’s design mapped a psychological journey — from model glamour to stripped-down starkness. Her silhouettes traced trauma without exploiting it, an exacting balance only she could manage.

Pukar (1983) brought one of their most striking collaborations: colour-blocked dresses inspired by the Mondrian effect — a decade before such silhouettes became mainstream again. The beach sequence “Samundar Mein Naha Ke” required Zeenat, who cannot swim, to roll in crashing waves while maintaining poise. Bhanu’s white outfit — minimal, architectural, perfectly secure — allowed the scene to stay playful rather than perilous.

In Mahaan (1983), shot in Bhaktapur Durbar Square, Zeenat and Amitabh Bachchan performed before hundreds of onlookers. Amid the chaos, Bhanu’s butter-yellow frilled costume held its shape and movement — a small example of the structural mastery beneath her apparent simplicity.

Across sixteen years and fifteen films, Bhanu and Zeenat developed a shared feminist and visual language: one of comfort, power, style and intelligence. A woman stepping into the frame on her own terms. Zeenat doesn’t sit at the edges of Bhanu Athaiya’s feminist vision; she sits at its centre. Here, sensuality belongs to the woman in the frame — not to the gaze watching her, and not to the story others want to impose on her.

Waheeda Rehman — Comfort as Power, and Bhanu’s Feminist Grammar

Waheeda Rehman came to Bhanu Athaiya long before the word feminism entered the vocabulary of Indian cinema, but their collaboration shows exactly what feminist costume design can look like: a woman designing for another woman’s comfort, dignity, and intelligence — never for spectacle.

Their relationship began on C.I.D. (1956). Waheeda remembered that first meeting with unmistakable clarity: Bhanu was the only designer who insisted on understanding every element of the scene — the emotional beat, the character’s inner state, the logic of the moment. “She wanted to know the detail of the character and the emotion… she was the only person in those days who did that,” [13] Waheeda said. That instinct — to centre the performer rather than the camera — became the foundation of their work together.

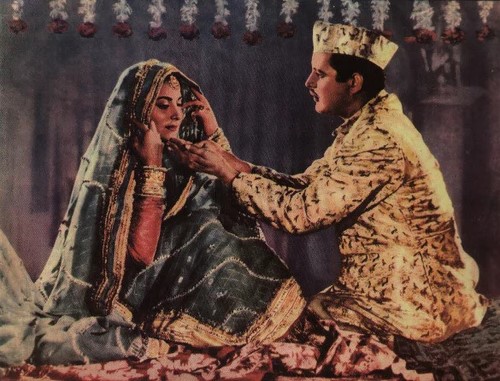

Waheeda Rehman in Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960)

For Chaudhvin Ka Chand (1960), Bhanu immersed herself in Lucknowi tehzeeb. She met families in Bombay who still carried Urdu etiquette in their bearing, watched how the dupatta was lifted, how a woman turned her head, how a gharara moved when seated. She worked with embroiderers from Uttar Pradesh who had inherited generations of craft.

Bhanu wrote in The Art of Costume Design:

Waheeda had the amazing ability to adapt to any role, and her beauty both surprised and fascinated me… She trusted me to design her outfits and allowed me complete freedom in my work.[9]

This freedom was mutual. Waheeda entrusted Bhanu to honour her boundaries; Bhanu, in turn, painted her as she wanted to be seen on the screen, in ways that gave Waheeda complete ease — the ability to cover, express, or move precisely as the role demanded.

The newly surfaced photograph of Bhanu wearing Waheeda’s gharara–kurta — taken by Bhanu’s husband — is central to that story. She draped and tested the outfit herself before sending it to set. Bhanu entered the costume to understand the woman who would inhabit it. That is feminist craft: treating the performer’s body as the starting point, never an afterthought.

Bhanu Athaiya testing Waheeda Rehman's costume for Chaudhvin Ka Chand before sending it to the production house set.

Image Courtesy: Radhika Gupta

But it is in Guide (1965) that Bhanu’s feminist grammar becomes unmistakable. Rosie’s entire arc — from a controlled housewife to an independent artist — is told through costumes that allow her to move. At the start of the film, Rosie’s world is tightly enclosed — a stifling marriage, an oppressive household, a silenced artistic self. Her costumes in these early scenes reflect that reality: heavy saris, muted tones, stiff drapes. The silhouette mirrors the weight on her autonomy.

As Rosie begins to reclaim her identity as a dancer, the costumes shift almost imperceptibly. The fabrics lighten. The palette warms. The drape loosens. Bhanu introduces chiffon and georgette — materials that breathe, that allow movement, that ripple with even the smallest flick of the wrist. Rosie’s physical liberation becomes visible before she even utters it. Rosie’s liberation anthem, “Aaj phir jeene ki tamanna hai,” is inseparable from that visual language. Bhanu keeps the costume clean, unadorned—letting Waheeda’s expression and the decisive stride carry the liberation. Bhanu writes, "Waheeda, as Rosie, breaks away from the bonds of a stifling marriage to lead life on her terms. Here, in one of Hindi cinema's most beloved and spirited songs, 'Aaj Phir Jeene Ki Tamanna hai,' she is seen with Dev Anand expressing her newfound freedom." [9]

.jpg)

Waheeda Rehman in Guide (1965)

In the eight-minute song “Piya Tose Naina Lage Re,” Waheeda Rehman moves through one of the most technically ambitious song sequences of 1960s Hindi cinema. The song took weeks to film and demanded a design that could accommodate Kathak, Bharatanatyam, folk steps, and film choreography. Bhanu dressed Waheeda in a nauvari (nine-yard) saree that allowed her body to expand into the space instead of shrinking from it. This is where Bhanu Athaiya’s feminist craft becomes unmistakable.

Waheeda remembered clearly: “She said I am going to have it stitched… it looks like a Maharashtrian nauvari saree and yet you don’t have to go through the hassle of tying it.” And later, laughing at the memory: “I could jump and do so many things in the song… it was so comfortable and saved a lot of time.” [13]

Bhanu engineered a pre-stitched nine-yard nauvari, built like a salwar, preserving the authenticity of the regional drape without trapping the actor inside it. Bhanu’s starting point was simple: the actor must not fight her costume.

Waheeda Rehman in Piya Tose from Guide (1965)

The aesthetic choices were equally deliberate: a rust-orange nauvari; a pistachio-green blouse that echoed the classic colour pairing Bhanu associated with her own mother; hair pulled into a neat low bun with soft waves at the forehead; minimal jewellery to keep movement clean; ghungroos for sound. Nothing excessive. Nothing that claimed attention before the performer. It was feminist philosophy expressed through costume design.

By the time Bhanu and Waheeda reached Reshma Aur Shera (1971), their working relationship had deepened into complete trust. The production shot in the Thar desert under harsh conditions, and Waheeda recalls that Bhanu refused to work from a distance — she lived with the crew in BSF tents and travelled from village to village studying how local women carried themselves. “She went to the villages and studied how they sit, and how to cover their face… you have to cover your face like this with two fingers and not show more than one eye,” [13] Waheeda remembered.

The jewellery required for the character posed another challenge: the desert heat made the silver pieces burn the skin. In her interview with Prinseps, Waheeda recalls, “At daytime when it used to be very hot and this silver jewellery used to touch your skin and burn… I said, ‘Bhanuji, what can I do? [13] Bhanu then coated the underside with paint — a simple protective layer so Waheeda could perform without pain.

Across their films, a single pattern holds: Bhanu shaped ease into a working principle. Every adjustment, every refinement, protected Waheeda’s freedom to inhabit the role fully — to move, to think, to perform without strain. In that discipline lies Bhanu’s feminist grammar: a design practice in which a woman could work without hindrance, and therefore with complete agency.

“Take Care of Me”: Collaboration and Care

Athaiya’s practice was defined by collaboration and empathy. Recalling her first meeting with Meena Kumari during Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam (1962), she remembered receiving a rose and hearing the words, “Bhanu, take care of me” [2]

That exchange framed her approach: she designed not for effect, but for the woman herself. She listened to the actor, the script, and the moment. “That meeting itself inspired me to do everything I wanted to do for the heroine,” [2] she said. Her studio was a space where women could speak openly and move freely — a rare environment in a film industry where creative authority was largely male [14]

Texture and Tone: Painting Women into Narrative

Meena Kumari in Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam

Athaiya often said she worked “as a painter.” Designing for black-and-white cinema required translating colour into tone and texture. For Sahib Bibi aur Ghulam, she created three visual idioms: the Brahmo Samaj girl in austere weaves, the courtesan in layered ornament, and Meena Kumari’s Chhoti Bahu in resplendent weaves that reflected both splendour and constraint. She explained, “To translate everything in shades of black and white was an experience by itself. I inserted a few colours here and there, knowing the tonality they would create on the screen.” [15] Her control of fabric, tone, and line gave the costume a narrative role equal to camera and dialogue.

Amrapali — Research, Classicism, and the Feminine Ideal

Vyjayanathimala in Amrapali (1966)

The legend of Amrapali dates back to ancient India, around 500 BC, in the republican kingdom of Vaishali (present-day Bihar). Celebrated in Buddhist and Jain traditions, Amrapali has appeared over centuries as a woman of talent, beauty, and autonomy — a performer, a patron, and a figure woven into political and artistic memory. Naturally, her story moved across theatre, literature, and cinema, gathering new interpretations along the way.

The 1966 film Amrapali demanded a visual world that felt rooted in early Indian history without falling into cliché. Its iconic costumes were designed by Bhanu Athaiya, whose scholarly approach to cinema was shaped by her training at J. J. School of Art. She drew directly from her studies of Ajanta and Ellora — research she first undertook as a student — examining the drapery, jewellery, and body lines of classical Indian sculpture.

Radhika Gupta (daughter of Bhanu Athaiya) recalls that this was typical of Bhanu’s method: She worked from research → sketch → exact costume, a process so precise that her drawings were “reproduced exactly” by her team. The result was a silhouette that merged Ajanta’s apsara forms with the structure of traditional nine-yard drapes, creating a look that was both archaeologically grounded and fully functional for Vyjayanthimala, an accomplished dancer who needed complete freedom of movement.

In Amrapali, Bhanu’s costumes embody her larger feminist ethos. As Radhika notes, actresses trusted her deeply because she ensured they were never reduced to the male gaze. In this sense, Amrapali’s sensuality is not spectacle but sculpture — classical, self-possessed, and designed to honour the performer rather than objectify her.

The apsara silhouette she created went on to influence mainstream representations of divine or classical femininity for decades. But its power lies in Bhanu’s original vision: a costume built on research, dignity, and an artist’s understanding of the female form — a convergence of history and performance that remains unmatched.

Swadeshi by Design

Bhanu's respect for craft connected Bhanu to a larger generation of women who viewed design as a form of cultural renewal. Among them was Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay, whose revival of Indian handloom profoundly shaped Bhanu’s approach to cinema. Athaiya’s innovations were practical as much as aesthetic. She introduced stitched nauvaris, zip-up saris, and stretchable churidars that allowed actresses to move with ease. She created asymmetrical hemlines and designed pre-draped costumes for complex choreography. Each innovation was rooted in empathy. She understood that comfort was a condition of confidence — that freedom of movement was integral to the dignity of performance.

Vyjayanthimala and Dilip Kumar in Ganga Jamuna (1961)

She brought handloom into mainstream cinema for the first time in Ganga Jamuna (1961), using authentic Indian weaves and natural dyes to reflect the lived textures of rural women’s lives. “For the first time, actual Indian handlooms and handicrafts were used to make the costumes,” [9] she wrote. This commitment to indigenous textiles aligned her with Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay’s handloom revival — another movement led by women who saw craft as both cultural and creative empowerment.

Athaiya’s insistence on using local weaves was more than an aesthetic decision; it was a quiet assertion of Swadeshi by design. At a time when imported synthetics signified progress, she grounded cinematic glamour in the dignity of handmade cloth. Every thread carried a lineage of women’s labour — spinners, dyers, and weavers whose craft embodied self-reliance. By placing their work on screen, she connected the woman performer to the woman artisan.

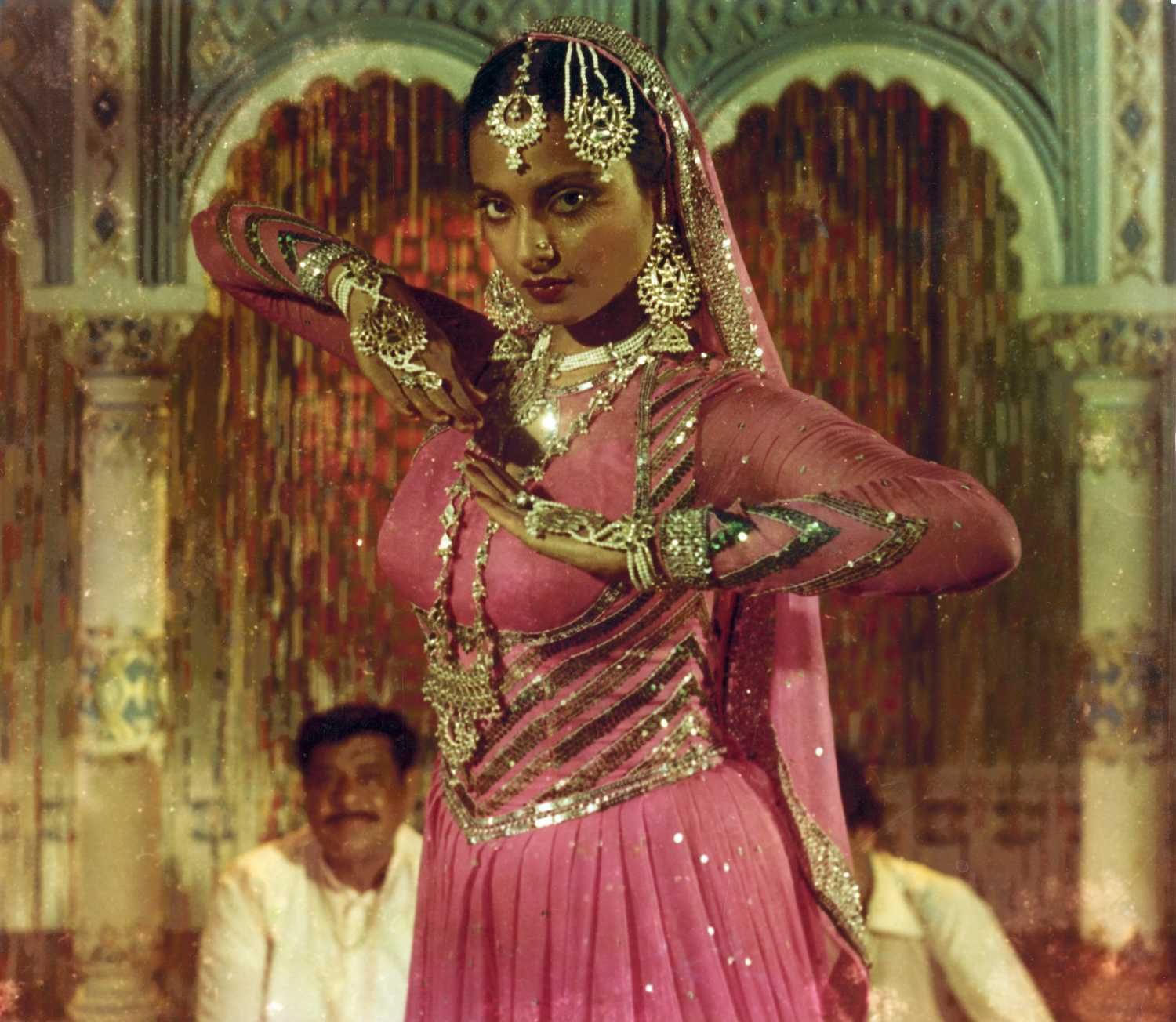

Rekha in Muquaddar ka Sikandar (1978)

One of her favourite materials was chiffon — a fabric she described as “one of the strongest, though it appears delicate.” [1] To her, its dual nature mirrored the women she dressed. Rekha recalled how Bhanu used chiffon in Do Anjaane and Muqaddar ka Sikandar to convey sensuality without excess — clothes that moved like breath yet held their form.

Across handloom and chiffon alike, Bhanu’s design practice remained grounded in respect for the performer’s body, the craftsperson’s labour, and the cultural histories embedded in textile work.

Helen: Movement, Precision, and Performance

Helen in Teesri Manzil. Costume Design by Bhanu Athaiya

Often celebrated as Hindi cinema’s dancing queen, Helen brought a level of grace, unabashedness, and musical intelligence that shaped an entire visual language of performance. Trained in Manipuri and Kathak, she danced with an instinctive feel for rhythm and camera. Jerry Pinto observes that “Helen’s face was almost as important in her dancing as her body… it echoed the words.” [16] Bhanu understood this completely and designed for the performer, not the typecast role.

Their collaborations spanned more than a dozen films — Hum Hindustani (1960), Dr. Vidya (1962), Kaajal (1965), Teesri Manzil (1966), Shikar (1968), Sau Saal Pehle (1970), Caravan (1971), Maryada (1971), Anamika (1973), Aaj Ki Taaza Khabar (1973), Madhosh (1974), Kachaa Chor (1977), Besharam (1977), Prem Bandhan (1979) and others — each revealing a quiet, assured understanding between designer and dancer.

In “Piya Tu Ab To Aaja”, Bhanu created two contrasting silhouettes — the gold shimmer and the red ruffled dress — designed to match shifts in tempo, pauses, and acceleration. The sculptural pink gown in “O Haseena Zulfon Wali” was built for movement: sliding down ramps, sharp directional switches, leaps, and Spanish-influenced spins. These choices weren’t ornamental; they were technical. Bhanu shaped garments that moved with Helen’s choreography.

Chosen fabrics allowed breath; seams and slits were positioned to support pivots and knee lifts; embellishment was placed so it caught light without interrupting rhythm. Even in her early black-and-white films — Hum Hindustani, Dr. Vidya, Kaajal — Bhanu’s palette and cuts were tuned to Helen’s stillness and expression, long before the high-voltage songs of the 1970s.

Jerry Pinto writes that Helen “left several myths lying around, myths that slowly began to become the stuff of legend.” [16] But what Bhanu recognised was something very particular to Helen — the way she could slip from stillness to sparkle in a single beat, how she used her face as rhythm, and how her dancing carried wit as much as allure.

Helen moved with a mix of mischief, precision, and complete assurance. Bhanu recognised that and designed in a way that never pressed down on her. The best numbers stay iconic because the costume steps back just enough for Helen’s performance to take the whole frame. A perfect collaboration between two women who were impeccably confident and sure of their craft

The Feminist Studio

Athaiya’s studio functioned as an atelier of collaboration. She tested costumes on herself, checked whether an actor could move, sit, turn, or dance without strain, and only then sent a garment to set. Tailors, embroiderers, and assistants worked under her quiet but unmistakable authority. She never raised her voice, yet everyone understood the precision she expected.

Her feminism was also anchored in self-reliance. She wrote that she began earning at eighteen and “remained self-sufficient since then,” a fact that allowed her to choose her projects, protect the actresses she worked with, and resist the compromises the industry often demanded of women. “Being a breadwinner,” she said, “gave me full freedom to do whatever I needed to do in pursuit of learning and creativity.” [3]

She described herself, almost modestly, as “a director’s designer,” [7] but the phrase never implied subordination. What she meant was dialogue — an honest give-and-take in service of the script. Her feminism lived inside that process: respect, clarity, precision, and the belief that every woman deserved ease on screen. For Bhanu, a costume was not something an actress had to endure. It was something she should be able to inhabit.

Women of History, Women of Imagination

This vision later extended beyond film into her designs for the Advani-Oerlikon calendars of the 1980s and 1990s. The 1994 edition, Who Says It’s a Man’s World, portrayed Rishikas, Brahmavadinis, and women of power drawn from Indian history and mythology. Each was treated not as a muse but as a thinker, warrior, or leader. The 1990 edition, themed on heroines who “put death before dishonour,” presented historical and mythological women through a lens of integrity rather than tragedy. Every costume was researched, drawn, and constructed with the precision of a painter’s hand (Prinseps Archive, 2024). These works reaffirmed her conviction that representation could restore women to the centre of visual history.

A Feminist Vision by Design

“At the beginning of her career, it would have been difficult to attribute to her a cultural plan. But as she went from film to film, from year to year, from decade to decade, Bhanu Athaiya created typologies of female beauty that struck a resounding chord with the great Indian masses. At the same time, cinema brought her to the masses, even as it allowed her to maintain her well-known reclusiveness.”

— Gayatri Sinha, Realizing a Dream, 2022

Across art and cinema, Athaiya redefined costume as a language of empathy and intellect. She gave her actresses comfort, credibility, and presence, ensuring that their image on screen carried their strength, not their submission. Her legacy lies not only in the costumes that survive but in the women she helped frame — seen, complex, and wholly themselves.

References

[1] Rekha. Rekha on Bhanu Athaiya. Prinseps Archive, 2023.

[2] Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya. Bhanu Athaiya on her first encounter with Meena Kumari. Prinseps Archive. 2024.

[3] Athaiya, Bhanu. The Role of a Woman in Cinema. Prinseps Archive.

[4] Sinha, Gayatri. Art and Design in the Life of Bhanu Athaiya. Prinseps Archive. 2023.

[5] Athaiya, Bhanu. Pages from Bhanu's Handwritten Notes. Prinseps Archive. 2020.

[6] Hoskote, Ranjit. Bhanu Athaiya: The Legacy of a Long-hidden Sun. Prinseps Archive. 2020.

[7] Bhanu Athaiya Designed for Success. Eastern Eye. 2020.

[8] Wilkinson-Weber, Clare M. The Dressman’s Line: Transforming the Work of Costumers in Popular Hindi Film. Anthropological Quarterly 79. 2006

[9] Athaiya, Bhanu. The Art of Costume Design. Harper Collins. 2010.

[10] Farook, Farhana. “EXCLUSIVE: ‘I Was Extremely Ambitious,’ Says Mumtaz.” Filmfare. 2024.

[11] Aman, Zeenat. Personal reflections on Satyam Shivam Sundaram. Instagram.

[12] Aman, Zeenat. Breaking Stereotypes: In Conversation with Zeenat Aman and Sujata Assomull. Prinseps Archive. 2024.

[13] Rehman, Waheeda. Bollywood Icon Waheeda Rehman on Academy Award Winner Bhanu Athaiya. Prinseps Archive. 2023.

[14] Vashisht, Mita. Mita Vashisht on Oscar Winning Costume Designer Bhanu Athaiya's Craft. Prinseps Archive. 2023.

[15] Athaiya, Bhanu. Bhanu Athaiya on Her Work in Hindi Cinema. Prinseps Archive. 2024.

[16] Pinto, Jerry. Helen: The Life and Times of an H-Bomb. Penguin Books, 2006.