Bhanu Athaiya: The legacy of a long-hidden sun

I.

It was D.G. Nadkarni, elder statesman among Bombay’s art critics, who first told me that Bhanu Athaiya had trained as a painter and had once shown alongside the members of the Progressive Artists' Group (PAG).

Like many of our conversations, this one took place at the Pundole Art Gallery in the early 1990s. Until then, I had known of Athaiya as a sophisticated and celebrated designer of costumes for the popular Hindi cinema; she had won an Oscar for Best Costume Design for Richard Attenborough’s 1982 masterwork, Gandhi.

A little later, I mentioned this conversation to Shaila Parikh, who confirmed what Nadkarni had told me. Founder of one of Bombay’s liveliest public platforms for art, the Mohile Parikh Centre for the Visual Arts, Shaila-behn counted among her friends many of the master spirits who had defined the direction of postcolonial Indian art.

Further confirmation came, years later, from Prafulla Dahanukar (née Joshi), artist and long-time committee member of the Bombay Arts Society, who had shared her studio with V S Gaitonde at the Bhulabhai Institute on Warden Road in the 1950s. Several of the Progressives had had studio spaces there; Ravi Shankar had run his Kinnara Academy for classical music at the Institute, where one of my cousins had been his student; and it was also the locus where Ebrahim Alkazi, the rising star of Indian theatre and champion of Indian artists, had held his rehearsals, lectures, and discussions. The Progressives and their associates were often in and out of Prafulla’s mother’s home in Girgaon – some of these impecunious young men were accorded refuge there, from time to time, when they found themselves temporarily without habitation.

When we find ourselves gazing, our breath taken away, at works like ‘Prayers’ (oil on canvas, c. 1950) and ‘Lady in Repose’ (oil on canvas, 1951), we recognise the degree to which cinema’s gain was painting’s loss.

Had Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya continued to practice as a painter, she would certainly have been a major presence in her pioneering generation of cultural practitioners in newly independent India. ‘Prayer’ is dominated by the figure of a female supplicant kneeling before an altar, her body stylized into a quasi-Cubist arrangement of angles and curves, yet with the texture and drape of the fabric, the pulse of a breath, the living human subject made palpable to us. That she is a nun is clear from the distinctive habit she wears, with its serge tunic and coif. She communes, in the sanctuary evoked by the artist through a burnished palette, with the cross that symbolizes the Saviour and His promise of salvation and redemption.

The palette, the evocation of chiaroscuro, the hushed tonality of the scene all unmistakeably suggest the unearthly darkened light, or perhaps the illuminated shadow, of a chapel windowed in stained glass.

And indeed, as we learn from Athaiya’s autobiographical notes, this painting may well draw on her own experience of such a sacred space when, as a student at Bombay’s Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art, she boarded at a girls’ hostel at a convent – unnamed in her notes; perhaps All Saints Convent Dockyard Road, Mazgaon, in one of Bombay’s oldest precincts.

Prayers by Bhanu Athaiya, circa 1950

“The place provided the much needed peaceful environment and the space to put up my easel and paint,” she writes. “The area around the convent was dark and lonely so one tried to get home quickly. The nuns lived and moved around in an area above the dining hall, below which were living quarters. There were girls from Tamil Nadu and even Sri Lanka… The whole experience at the convent was amazing. Watching their [the nuns] rituals, hearing them chanting, and being so closely connected to their daily lives had a huge influence on me since I had never seen or heard of anything like this before. The muted and deep hues during the normal days at the convent juxtaposed with the pageantry at Christmas Eve Mass in the Byculla Church inspired me to paint ‘Nuns’ as a tribute to them. Surprisingly, when the painting was exhibited at a French get-together with PAG, nobody saw it as something drawn from personal experience but insisted that I had done a copy of some foreign work.” The note trails off: “The play of light through the stained glass windows and glass arches above doors added.” [1]

I find it instructive that Athaiya’s evocation of a Roman Catholic chapel in Bombay should have been mistaken for a visual echo of a European work – this piece of reminiscence points towards the far larger and often vexed discussion around ‘Indianness’, which plagued India’s cultural sphere during the first few decades after Independence. In their quest for a supposedly pure Indian essence, many Indian thinkers proved merely auto-Orientalist, even as the modernist work of Indian artists was dismissed as ‘derivative’ by Western observers who expected, magically, to discover some exotic and purely native expression among the artists they met here. The point that this debate misses is that Indian culture – like all cultures everywhere – has, for millennia, been absorbent of diverse influences. And some elements within Indian culture form cusps and intersections with, for instance, European or Levantine culture.

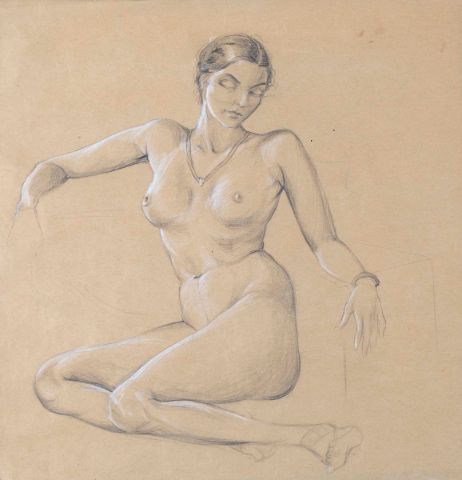

If ‘Prayers’ occupies the ground of the sacred, with a renunciate as its protagonist, ‘Lady in Repose’ is set at the opposite end of the experience: the worldly.

Its protagonist is a female nude, possibly a model at art school or a fellow student or resident at the hostel, reclining with her back and buttocks to the viewer. The brushwork creates a curtain of shooting lights, variations on the primaries of blue, red, and yellow, through which we approach the nude; the artist also sets up a netting that protects the nude from our prying gaze. While the protagonist of this painting is confident in her sensuousness, unself-conscious in her pose,‘Lady in Repose’ does not offer itself up for the delectation of the male gaze. If anything, we are made aware of our questionable locus as viewers of a private, even intimate moment. This painting is not the work of an acolyte of male masters. It is, already – the artist was 21 – the work of an artist whose sensibility would be described as feminist today, a woman who knew her mind and would make her way in the world.

Lady in Repose by Bhanu Athaiya, 1951

Bhanu Athaiya’s self-confidence was rooted in her earliest years. Born Bhanumati Annasaheb Rajopadhye, she grew up in a family that balanced its traditional Brahmin lineage with a newly emergent cosmopolitan modern sensibility in Kolhapur. Her father, Annasaheb Rajopadhye, was a painter, an accomplished amateur photographer, and a film-maker. Although he died when she was barely ten years old, Annasaheb had already set his daughter off on her journey. His memory would always be an inspiration to the future artist and costume designer. He had directed several films in Marathi and Hindi and had given his family wide exposure to cinema, music, and theatre.

In her autobiographical book, The Art of Costume Design (2010), Athaiya paints a loving portrait of this multi-talented figure:

“My father was a self-taught artist. He would study techniques from art books. He painted portraits in oil on canvas in the British academic style. He would make frequent visits to Bombay and bring back books on European painters like Leonardo da Vinci, Rembrandt, and Turner, among others… Father would encourage everyone in the family to pursue their artistic talent. He bought fine silk skeins for my mother to do compositions of birds and landscapes, and books on embroidery patterns, drawn thread work, and cutwork. He also bought a Singer sewing machine for her and other tailoring paraphernalia. He would bring along catalogs with fashion plates showing pictures of hats, fur coats, gowns, pretty blouses, and pullovers from the Army and Navy Stores. … Noticing my interest in art, my father engaged a person to teach me papercraft when I was eight years old.” [2]

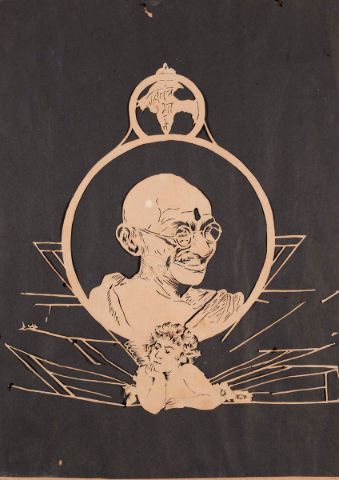

Gandhi by Bhanu Athaiya, 1938-39

After seeing ‘Red Oleanders’, an English adaptation of Tagore’s symbolist play, Raktakarabi, the Rajopadhyes met the director, Hima Devi Kesarkodi. Theatre person, dancer, and elocutionist, Hima Devi was always delighted to discover young protégés (a little over four decades after these events, she would teach the present writer drama at school). Struck by the young Bhanu’s talent, she recommended strongly that the child be enrolled at the Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art, Bombay. This conversation laid the foundation for her career. After finishing school, Bhanu would move to Bombay, where she would live with Hima Devi’s mother, Meera Devi, in the garden suburb of Khar. She would take a train every weekday to Churchgate, South Bombay, and go to the art school, housed in a distinguished neo-Gothic building near Victoria Terminus.

It was through Meera Devi, who was the assistant editor at the Fashion & Beauty magazine, that Bhanu would enter the domain of fashion design. The editor of the magazine, Kishen Jhangiani, had just returned from a course of study in Paris; he liked Bhanu’s sketches, which Meera Devi had shown him, and she began to work as an illustrator at Fashion & Beauty. In the spirit of the time, which simultaneously looked back to India’s civilizational glory and forward to its modern future, her mandate was clear:

“I had to draw inspiration from India’s heritage and showcase it in my fashion designs.” [3]

II.

As I have observed earlier in this essay, members of the Bombay art world’s older circles – in whose lives the visual arts, cinema, music, architecture, and theatre intersected closely – were perfectly aware of Bhanu Athaiya’s work as an artist, before she left it behind to achieve excellence and fame as a costume designer for cinema. This has, however, come as news to the younger generation that has only recently discovered Athaiya and presented her to the public as a Progressive long lost to view; indeed, as the only woman Progressive.

While such claims make for sensational effect, Athaiya’s substantial and accomplished body of paintings and drawings calls, not only for a more sober approach to art-history writing but also for an engagement with the cultural contexts of early and mid-20th century western India that played a crucial role in forming her sensibility.

These contexts have unjustly been consigned to oblivion, erased from a dominant narrative in which modernism is believed to arrive on the Bombay art scene only with the dramatic emergence of the Progressive Artists' Group in the late 1940s.

The story goes – and I cannot plead innocence either;

we have all, at one or another time, participated in this myth-making project – that the Group arose through the fortuitous conjuncture of several talented young Bombay artists, to whom three Central European émigré patrons, like magi, brought news of European modernism.

These young artists also received enthusiastic support from an adventurous Bombay frame-maker and gallerist. Thus blessed, their vigorous modernist work put in the shade the effete production of the academic realists and society painters who are said to have dominated the annual salons of the Bombay Art Society. This charming nativity account is analogous to the foundation stories of many religions, in which the advent of the prophet, mystic or righteous teacher of choice is said to have been preceded by a period of darkness, ignorance, or decadence.

My aim is not to demean the historic contribution of the Progressives and their circle, whose work I have studied, written about, and curated over several decades; nor do I wish to detract from the equally historic contribution of their early patrons and supporters, Walter Langhammer, Emmanuel Schlesinger, Rudolf von Leyden, and Kekoo Gandhy. My aim, instead, is to draw attention to the more complex actuality of the Bombay of the 1930s and 1940s, decades of intense artistic ferment in the city, with many remarkable artists of several generations and stylistic orientations at work. And let me state this emphatically: there were more continuities than disjunctures between the Progressives and their unsung contemporaries than we might be led to believe by the classic avant-garde narrative, with its notions of a complete rupture with the foregoing and an autogenesis of the dramatically new. I return to the conversation with Prafulla Dahanukar mentioned earlier, the unlikely venue for which was a wedding reception at one of the clubs on the windswept corniche of Marine Drive. Seated at a banquette, she sketched for us a floor plan of the Bhulabhai Institute, showing where the studios of various artists had been located. As I was speaking of the Progressives, Prafulla stopped me in mid-sentence with a supremely relevant caveat.

“Arre ka Progressives-na gheun baslaayes,” she said in her genially peremptory manner. “To kaalkhand hota Bombay artists cha.” Which, translated from the Marathi, means: “Why are you so hung up on the Progressives? That was the epoch of the Bombay artists.”

She proceeded to recite a string of names of long-vanished painters, some of whom appear in the catalog for the September 1953 ‘Progressive Artists’ Group’ exhibition in which Bhanu Rajopadhye, then 24 years old, was invited to show two of her paintings, one of which was ‘Prayers’.

Among the eleven artists featured in the show were, in addition to Rajopadhye, five of the PAG’s six founder members, K.H. Ara, H.A. Gade, M.F. Husain, S.H. Raza, and F.N. Souza, as well as their friend and close associate V.S. Gaitonde, and the inducted PAG member Krishen Khanna, who also wrote the elegant introduction to the catalog. There were also three other artists: N.D [Noshir] Chapgar, G.M. Hazarnis, and A.A. Raiba. Of these three, Chapgar and Hazarnis have never been regarded as members of the PAG; Raiba showed with the group in 1952 and 1953 but soon realized that his style, oriented towards India’s miniature traditions, had nothing in common with the more School of Paris-leaning painterly ambitions of the PAG. So much for the mystique of what has been eulogized as the ‘last exhibition of the Progressive Artists’ Group’, the composition of which very likely had less to do with shared artistic ideology and more to do with the bonds of friendship and collegiality – and the humdrum imperative of pooling resources together to rent the exhibition space. This form of tactical collaboration towards a group show was an established feature of life in the Bombay art world from 1952, when the Jehangir Art Gallery opened its doors, until the decisive rise of commercial galleries in the metropolis during the 1990s. It was certainly the norm in the 1950s and 1960s when the Jehangir Art Gallery at Kala Ghoda, the Artists Aid Centre (later the Artists Centre) on Rampart Row, and the Taj Art Gallery on the Apollo Bunder seafront were the only available venues for exhibition.

The accepted canon of modern Indian art, as fixated on the Progressives, is no older than the 1990s, as I have argued elsewhere – in my curatorial essay for an exhibition of modern Indian art drawn from the Abby Weed Grey collection, which is part of the New York University Art Collection. It results from the auction-house economy’s embrace of a series of influential publications and exhibitions, unfolding over the 1990s, as the conceptual foundation of their enterprise. [4]

Likewise, in their curatorial essay for an exhibition drawn from the collection of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, Mumbai, the art historians Mortimer Chatterjee and Tara Lal have demonstrated the fatuity of constructing a canon that privileges the Progressives as the only major artists on the Indian scene in the 1950s and 1960s. [5]

Chatterjee and Lal argue from the representative diversity of the TIFR collection, as do I from the same sparkling heterogeneity of the Abby Weed Grey collection, both of which cover the same historical period or, in Dahanukar’s evocative phrase, kaalkhand. We take, as our key source of inspiration, a passage from a 1965 essay by the artist, critic, and cultural thinker Badri Narayan, who formulated the term, ‘the artists of the third epoch’, to convey his historical moment.

“The First Epoch in modern Indian art belongs to what is now called the Bengal School led by Abanindranath Tagore." Narayan wrote, “the Second to independent and stylistically divergent painters like Jamini Roy and Amrita Sher-Gil; and the Third to those many painters, too numerous to be named individually, too varied in their outlook, those artists who emerged about the 1950s of this century, turning for inspiration not only to their own primitive, prehistoric and the more archaic and early miniature traditions but also to the makers of the new patrimony – Klee, Mondrian, Miro, Villon, Brancusi, Moore, Orozco, Marini, Giacometti, and the host of those eclectic masters of the post-impressionist period. The significant [artists] after 1947 are men like Hebbar, Husain, Bendre, Souza, Padamsee, Gade, Subramanian [sic], Ram Kumar, Sankho Chowdhuri [sic], Davierwalla, Raman Patel, Chavda, Raza, Gaitonde, Ara, Samant, P T Reddy, KS Kulkarni, Satish Gujral, Chintamoni Kar.” [6]

III

It will be my endeavor, here, to demonstrate that Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya’s work as an artist – most of it achieved between 1945 and 1952, after which date she made her career as a sophisticated contributor to the Hindi cinema – had little to do with the influence or tutelage of the Progressives.

In any case, the Progressives did not come together until 1947-1948, and constituted, as I have argued elsewhere, more a moment than a movement, its ephemeral existence assuming fleshly solidity in the nostalgic retrospection of artists, art critics, and art historians rather than in the reality of its brief apogee. The Group was unified by friendship and shared circumstances rather than a coherent aesthetic or political program. Even the name of the group is deceptive: it came from Souza’s short-lived flirtation with Communism, an ideology from which some of his confreres, such as Husain and Raza, and associates such as Gaitonde and Padamsee, maintained a cautious and conservative distance. The refined and multilingually well-read Khanna was doubtless well attuned to the analogy Souza intended with the Left-wing Progressive Writers Association (PWA), whose members included a constellation of brilliant Urdu writers including Saadat Hasan Manto, Sahir Ludhianvi, Ismat Chugtai, Kaifi Azmi, Sajjad Zaheer, and Rajinder Singh Bedi. However, it is unlikely that Khanna, as a young merchant banker – he had joined the Grindlays Bank in 1946, from which he would resign to set out as an independent artist only in 1961 – would display any manifest enthusiasm for an anti-capitalist position.

It is a very Indian tendency to sanctify one or another artist, as one re-discovers or re-contextualizes them, with a membership of the Lodge of Initiates or chosen sampradaya – in other times and places, we have seen this happen with the Kerala radicals, for instance. In the case of the Progressives, it seems pointless, especially when some of those seeking to be sanctified in this manner were strikingly vigorous talents well launched on distinctive trajectories of their own, such as Mohan Samant and, indeed, Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, had she chosen to make her career in art. As against this unproductive circling around a chimera, I will propose that Athaiya’s artistic practice had its origins and deep historical horizons in three formative contexts, three other genealogies of the Indian modern.

The first of these is the ethos of patronage for the arts and culture within the network of the native Princely States, which – alongside the territories ruled by the British Crown and the few enclaves ruled by France and Portugal – formed a vital element in the patchwork quilt of colonial India. Among the most progressively minded and culturally inclined of these princely states were Mysore, Travancore, Baroda, Indore, Aundh, and Kolhapur, where Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya was born and grew up.

Far from being a backwater – as ignorant observers resident in Bombay may imagine – Kolhapur was a cultural hub, energetic in its contribution to visual arts, cinema, theatre, music, and culture at large.

It was a node in a larger cultural topography that extended across Bombay Presidency, several princely states, a swathe of territory in what is today north Karnataka, as well as two swathes, one that was then part of the Central Provinces & Berar, and another that was then in the Nizam’s Dominions, which are today part of Maharashtra. Kolhapur demonstrates with compelling clarity that a city does not have to be metropolitan to be cosmopolitan. It can retain its small-town scale and warmth while being open and responsive to the globe’s finest offerings.

In Kolhapur, too, the legendary reformist ruler Chhatrapati Shahu Maharaj (1874-1922) and his son and successor Chhatrapati Rajaram III (1897-1940) were visionaries and philanthropists who extended their moral and material support to a wide array of causes. These two rulers of the Bhosale dynasty – descendants of Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj – were at the forefront of the anti-caste and anti-untouchability movements, and played a stellar role in the process of the social revolution that would be taken to its Constitutional conclusion by the towering figure of Dr. B R Ambedkar, whose work they supported. Shahu Maharaj also patronized the physical culture movement, with its performances of mall-khamb and kushti by the pehelwans or wrestlers. Kolhapur nurtured a renowned tradition of tamasha, Maharashtra’s popular dance-theatre form. During the Shahu renaissance, Kolhapur also emerged as an early hub of cinema, with such pioneers of the classic age of silent cinema as Baburao Painter (who was also an artist) and such studios as Kolhapur Movietone being active there. Like the Pant Pratinidhis, who ruled the princely state of Aundh, near Poona (now Pune), the Bhosales also collected art and displayed it, inviting the general audience to view it on specific occasions, thus inaugurating a museum culture in Kolhapur.

Among the artists that Kolhapur produced were such renowned figures as Abalal Rehman and Mahadev Vishwanath Dhurandhar, both trained at Bombay’s Sir JJ School of Art. Abalal became Shahu’s court painter; Dhurandhar became the Headmaster, or seniormost Indian teacher, at his alma mater in Bombay, as well as a sought-after society painter and a popular illustrator. Meanwhile, the entrepreneurial Kirloskar family developed a printing and publishing center at their industrial township of Kirloskarwadi near Kolhapur, and were important contributors to the art scenario; distinguished artists vied to produce cover designs and images for their triad of magazines, Kirloskar, Stree, and Manohar. The Rajaram Art Society, named after Kolhapur’s then-reigning monarch, was established in 1934. Sustained by distinguished artists as well as prominent citizens, its program of exhibitions addressed a larger audience for the arts. [7]

Such was the ethos within which Athaiya grew up and recognized her calling in life. As she writes in an autobiographical note:

“Artist Dhurandhar’s paintings were displayed at the Kolhapur Palace. It was a common sight to see artists with their easels propped up and painting at scenic spots like the Mahalakshmi Temple, around Rankala Lake, and on the banks of the Panchganga River. All this caused a deep impression on me and I took to drawing at a young age. At the high school annual competition, I won three awards for my paintings on a flower study, a glass painting, and a sketch of a young girl with a deer, the latter inspired by a Grecian-style sculpture.” [8]

Coming to Bombay by Bhanu Athaiya, circa 1948

Coming to Bombay by Bhanu Athaiya, circa 1948

IV.

The second of Bhanu Athaiya’s formative contexts is the pedagogy of the Sir Jamsetjee Jejeebhoy School of Art as shaped and articulated during the successive regimes of Principals Gladstone Solomon and Charles Gerard, with its emphasis on a Bombay Orientalism, and its lineage of influential pedagogues, including M V Dhurandhar, G H Nagarkar, Jagannath Ahivasi, and R D Dhopeshwarkar. The JJ School and its pedagogy have far too often been under-regarded and neglected, as – in the view of its detractors – being tainted by British academicism and Orientalist exoticism, and therefore unworthy of notice, eclipsed by Santiniketan and Baroda. This is most unfortunate, for JJ’s history offers testimony to a complex set of artistic negotiations within the late-colonial culture. My entry point into the history of the JJ School of Art pedagogy will begin, perhaps to the bafflement of some readers, with Alphonse Mucha (1860-1939), a painter, illustrator, and graphic artist of Czech origin and a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire who had shaped his career in Paris in the late 19th century. Some of the most celebrated posters and advertisements of the Art Nouveau period were created by Mucha. In the second half of his career, he returned to his native region of Bohemia-Moravia and aligned himself with the rising Slav nationalism that would eventually result, after the collapse of the Austro- Hungarian Empire, in the emergence of Czechoslovakia. Mucha’s Art Nouveau phase had an international following; one of his votaries was Gladstone Solomon (1880-1965), an artist of South African Jewish origin who had studied at the Royal Academy, London. After having served as a soldier in World War I, Solomon came to Bombay, where he held the positions of Principal of the Sir JJ School of Art (1918-1937) and Curator of the Prince of Wales Museum, now the CSMVS (1921-1937). Solomon transformed the JJ’s South Kensington-style syllabus, with its emphasis on the decorative arts, by instituting a Royal Academy-style emphasis on draughtsmanship in life classes, where students drew and painted human figures from the life, both clothed and nude.

At the same time, he developed an idiom of Bombay Orientalism to compete with the acclaimed Indic twilight style, as one may describe it of the Bengal School. Its artists – among them Abanindranath Tagore, Asit Kumar Haldar, and Abdur Rahman Chughtai – drew on the exemplars of Mughal, Rajput, Safavid, and Qajar painting.

As Partha Mitter writes, Solomon and his colleagues “simply could not ignore the ‘language’ of Indian art, as enunciated by the Bengal School. Solomon proceeded to earn it with alacrity if only to beat the enemy at his own game.” [9]

Solomon set his students to render episodes from the Sanskrit epics, dramas, and poem cycles into a strikingly hybrid and exotic style in which the figures were inflected by Mucha, yet also retained a naturalism, while the Jaina and Rajput miniatures asserted their distant imprimatur too. Alongside, students at the JJ during the Solomon regime were also trained in the tradition of the miniatures, so that they were intensely at home in multiple historical lineages and cultural climates (in the late 1940s, Bhanu Athaiya would study the miniature techniques and their adaptation to a contemporary situation under one of Solomon’s students, Jagannath Ahivasi, whose name had come to be synonymous with this artistic choice).

In 1921, Solomon led his students to the Ajanta Caves, insisting on the ‘scientific’ character of their image-making techniques and derogating the Bengal School’s mystical cultural- nationalist idea that they embodied the overflow of religious devotion. Copies of the Ajanta murals had already, famously, been made by the students of the JJ School under Principal John Griffiths between 1872 and 1881, but the Bengal School had monopolized the Ajanta cult by setting in motion the practice of artistic ‘pilgrimages’ to this ‘shrine’ in 1909, at the height of the anti-colonial Swadeshi movement of self-reliance and self-rule that had begun four years previously in Bengal. [10]

In 1928, as colonial India’s new capital, New Delhi, being designed by the architects' Herbert Baker and Edwin Lutyens, began to gain concrete shape, Solomon secured for his students a prestigious commission to decorate the Imperial Secretariat. Lutyens was resolutely opposed to the involvement of Indian artists in the project; Baker was just as resolutely committed to engaging Indian artists for it. Fortunately for Solomon, the Imperial Secretariat fell within Baker’s domain. [11]

As Curator of the Prince of Wales Museum, Solomon ensured that the works of his prize pupils were acquired for its collection throughout the 1930s. Through the optic of an exhibition I curated at the museum, ‘Unpacking the Studio’, I have shown these works from the reserve collection, demonstrating the seamless and delightfully nepotistic, although historically productive, continuity between pedagogy and museum practice. [12]

The now seemingly forgotten watercolorist and art historian N M Kelkar, who wrote the painstakingly researched, detailed and substantial text for a centenary volume of the JJ School in 1957, bears witness to the influence of the Solomon pedagogy (I have preserved Kelkar’s charmingly old-fashioned colonial spelling of proper and place names): “Scores of private schools trained students who appeared at the examinations held in Bombay, and the influence of the methods followed in the Sir JJ School extended to wider areas such as the native Indian States. Some governments gave scholarships and sent students to Bombay for training. Nagpur, which belonged to another Presidency called the CP and Berar, and the native States helped students with scholarships because they had no schools of their own.

Baboorao Painter and his colleagues trained landscape and figure painters as vocational apprentices, but Mr. Dalvi had a class in Kolhapoor teaching students who appeared at the examinations held by the government. [13] Rippling out from Solomon’s pedagogy at the JJ School and his successes within the colonial system of patronage – and feeding even into the greater receptivity to European Modernism advocated by his successor as Principal Charles Gerard – this Bombay Orientalism became endemic to much of the art being produced in western India between the 1920s and 1940s.

As a child and teenager, Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya was certainly exposed to this idiom, and it informs a number of her works, including ‘Women holding pots’ (watercolor on paper, c. 1945), ‘Ranga Mahotsava’ (watercolor on paper, c. 1950), and ‘Vishwamitra’ (watercolor on paper, c. 1950).

Women holding pots by Bhanu Athaiya, c.1945

Women holding pots by Bhanu Athaiya, c.1945

Ranga Mahotsava by Bhanu Athaiya, c. 1950

Vishwamitra by Bhanu Athaiya, c. 1950

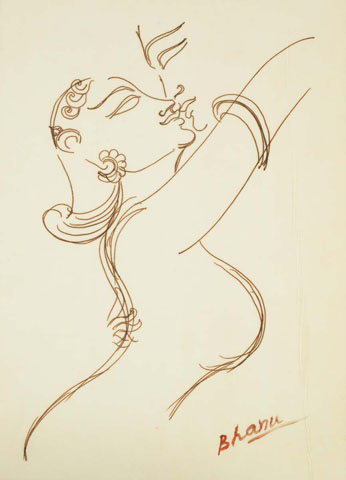

A sheaf of her sketches and drawings from her student years at the JJ School attest to its pedagogical amplitude: they embrace sculptural details from temples such as Khajuraho, presumably copied from photographs, as well, as well as portraits and nudes from the life, and fantasy figures.

Temple Sketches by Bhanu Athaiya

Temple Sketches by Bhanu Athaiya

Nude Study of Woman sitting with White Accents by Bhanu Athaiya, 1949

Bust Geometrical Plan of a Sculpture by Bhanu Athaiya, circa 1948

V.

Looking back on her life in Bombay as a young woman in her twenties, Athaiya would write of herself and her artist contemporaries, “We would often meet at social get-togethers at Mulk Raj Anand’s place in Colaba, where we used to meet the likes of Ebrahim Alkazi and discuss the latest trends and happenings in the world of art. I distinctly remember many discussions about a painting by Alkazi, that of Christ.” [14]

This reminiscence brings me to the third formative context for Bhanu Athaiya’s artistic development that I have in mind is the vibrant cultural and artistic scene of Bombay in the early years of Independence, when she was an art student.

The west-coast metropolis was home, also, to an ensemble of gifted artists including, among others, K K Hebbar, Shiavax Chavda, and R D Raval. Bombay’s cultural life in the 1940s and 1950s was dominated and shaped by an array of magisterial visionaries and institution-builders including the scientist and science administrator Homi Bhabha, who was a leading patron and institutional collector; the novelist and art critic Mulk Raj Anand, founder editor of Marg magazine; the novelist and cultural thinker Raja Rao; that champion of artists, Kekoo Gandhy, who would establish one of Bombay’s earliest private galleries, Chemould, in 1964; the collector and historian Karl Khandalavala; the patron of the arts, Sir Cowasji Jehangir; the Central European émigré connoisseurs and collectors Rudolf von Leyden, Walter Langhammer, and Emmanuel Schlesinger; and the polymathic theatre-maker, artist, collector, gallerist, and archivist Ebrahim Alkazi.

In my curatorial essay for an exhibition of the polymathic theatre-maker, Alkazi’s early paintings and drawings restored to public view for the first time in many decades, I wrote of some of these dazzling figures and offered a glimpse into the cultural domain they had created in late colonial and early postcolonial Bombay: “Offered studio and rehearsal space at the Bhulabhai Institute, where Ravi Shankar ran a music academy, Kinnara, and artists like M F Husain and V S Gaitonde had studios, Alkazi inaugurated an ambitious program of theatre training [Theatre Unit]. Internationalist in perspective, Alkazi invited visiting speakers to lecture at the Institute and interact with its members. Among these visitors were the dancers Martha Graham and Jean Erdman, the poet Stephen Spender, and the artists Isamu Noguchi and Alexander Calder. Alkazi’s Bhulabhai experiment has a pivotal centrality in the history of modernism.… Whether or not they used this term as self-identification, Alkazi and his Bhulabhai circle were caught up in the historic project of casting themselves as a self-aware, critically nimble and dynamic avant-garde.” [15]

It is no surprise that Bhanumati Rajopadhye Athaiya, nourished by such a lively and multidisciplinary stream of stimuli, would seek larger horizons for her creativity. That she chose cinema over the visual arts for the expression of her creativity does not, in any way, diminish her aura or her place in India’s cultural history. At most, the dominion of the visual arts may wish her work had never slipped off the radar for nearly seven decades. It returns to us now, although she has passed into the ages – in homage to the name by which she was known, ‘Bhanu’, let us regard it as the legacy of a long-hidden sun.

Ranjit Hoskote

Notes

[1] Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, undated handwritten notes.

[2] Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, The Art of Costume Design (Noida: HarperCollins, 2010), pp. 11-14.

[3] Ibid., p. 24.

[4] Ranjit Hoskote, The Disordered Origins of Things: The Art Collection as Pre-canonical Space’, in Susan Hapgood and Ranjit Hoskote, Abby Grey and Indian Modernism: Selections from the NYU Art Collection (New York: Grey Art Gallery/ New York University, 2015), pp. 41-51.

[5] Mortimer Chatterjee and Tara Lal, The TIFR Art Collection (Mumbai: Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, 2010).

[6] Badri Narayan, ‘Artists of the Third Epoch’, in Lalit Kala Contemporary 3 (New Delhi, 1965), p. 22.

[7] For an account of this cultural topography, see Ranjit Hoskote, ‘Celebrating the Sthala-Purana and the Sandhi-sthana: The Polycentric Cultural Universe of Rethinking the Regional’, in Sheetal R. Darda & Manisha Patil eds. Rethinking the Regional: Mapping the Art Movements of Maharashtra (Mumbai: National Gallery of Modern Art Aurangabad: Shlok, 2015), pp. 14-17.

[8] Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, ‘Bhanu Rajopadhye’s association with the Progressive Artists' Group (typescript dated ‘Bombay: May 2010’).

[9] Partha Mitter, The Triumph of Modernism: India’s Artists and the Avant-garde 1922-1947 (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 186.

[10] Ibid., p. 187.

[11] Ibid., p. 194-202.

[12] The exhibition I flag here was a contextualization of the artist Jehangir Sabavala (1922- 2011) in terms of his early training at the Sir JJ School of Art, as against his better-known education at the Heatherley School of Art, London, and the Academie Andre Lhote, Paris. See: Ranjit Hoskote, Unpacking the Studio: Celebrating the Jehangir Sabavala Bequest (Mumbai: CSMVS, 2015).

[13] N M Kelkar, Story of Sir JJ School of Art 1857-1957 (Bombay: Sir JJ School of Art, 1957) pp. 97-98.

[14] Bhanu Rajopadhye Athaiya, ‘Bhanu Rajopadhye’s association with the Progressive Artists' Group (typescript dated ‘Bombay: May 2010’).

[15] Ranjit Hoskote, Opening Lines: Ebrahim Alkazi, Works 1948-1971 (New Delhi: Art Heritage), p. 39.

Ranjit Hoskote

Ranjit Hoskote is an Indian poet, art critic, cultural theorist, and independent curator. He was honored with the Sahitya Akademi Award for lifetime achievement in 2004.