The art of portraiture seems much more enticing today when we live in a world where ‘portraits’ can be created at the click of a button with a single handheld device. There is something enigmatic about how artists in the past captured personalities with strokes of the brush and immortalized them in portraits. There is something romantic about the notion of portraits themselves, and how a sensitive artist could capture the physical characteristics as well as the psychological aspect of the subject of the portrait.

One can view the spectacular portraits painted by Atul Bose (1898-1977), against the background of the Indian art scene of his times. Key amongst this is the impact of European painting style on Indian portraiture art as well as the introduction of the camera.

“Significant changes were also seen in the realm of portraiture with the introduction of European academic naturalism and artists being trained in the newly emerged art schools. The methodology of the artist for making portraits also underwent a slight change with the invention of the camera and its usage in India during the 1850s,” writes Shalvi Agarwal in an informative catalog by Manan Relia.[1]

She also points out another key development- the use of portraits as a highly personalized form of gifting.

In the same document, [1] in a write-up chronicling Portraiture in India, Dr. Ratan Parimoo points out that no independent status was given to the genre of portraiture though it gained in popularity since the second half of the 19th century in the oil medium by Indian painters. He mentions that while one may be tempted to hold the view that the influence of traveling European artists working in India had something to do with this, and while the influence of artists such as Raja Ravi Varma, who painted portraits in oil revived this interest, one must also look at the influence of the phenomenon of naturalism that was prevalent in the art schools around the country. Also, there was an opportunity for employment in the realm of portrait making.

While the time's post advent of East India Company was ripe for portraiture to gain steam, one must also keep in mind that Indian history is marked with examples of portraits.

“Even during the 18th and 19th centuries art of portraiture was vigorously pursued in Rajasthani sub-schools as well as in sub-schools of Pahari kingdoms, besides the late phase of the Mughal style in Delhi, Audh and Murshidabad,” writes Dr. Parimoo. Hence, one could conclude that what was new was perhaps new ways of seeing light, color schemes, and such technicalities.

It is because of these influences that were dominant in the Indian portraiture scene that one must view the work of Atul Bose.

Atul Bose (India, 1898-1977)

Atul Bose was a prolific Indian painter and graphic artist. He was born in Mymensingh, East Bengal, in 1898. His skills were honed first at the State College of Arts and Crafts in Calcutta (1916–18). Later on, he also became Director of this Institute. His particular skill in representing people in portraits won him accolades early on.

A sketch of the educationist Asutosh Mukherjee, known as 'Bengal Tiger', won him a scholarship to study art at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (1924–26). It was to be a fruitful stay as he learned some vital lessons during his stay in England. He worked with English post-Impressionist Walter Sickert whose influence could be detected in Bose's use of grey and brown in some of his later works. [2]

Art and Academia

Bose was one of the founders of the National Academy of Fine Art in Calcutta in 1919. He had also been the Director of the Government Art School, Calcutta during 1945-1948. While one hears of ‘politics’ in varied fields, it is interesting to note that Bose’s time at the Government Art School was marked with differences with Mukul Dey [3], and this simmering difference played out in the background whilst he conducted his academic activities. If one digs deeply, one finds this engagement with the academic aspect of art education in varied forms. For example, in articles that he wrote for art journals [5]

At that time the Bengal School was prominent in influencing art education. Bose is known also for the efforts to infuse the influences of realism.

Hence, “Academic Realism upheld by the art school training was never completely abandoned in favor of the Bengal School. Thus the nationalist art movement led by Abanindranath and Nandalal Bose was accompanied by a parallel movement upholding Academic Realism led by Hemendranath Mazumdar and Atul Bose,” [8]

Not surprisingly then, Bose is seen as a pioneer in the field of Indian art education, and “his artistic achievements are throughout punctuated by his engagement with various art institutions and his tireless attempt to assimilate what was considered an alien language within the indigenous culture,” (see 2).

Bose’s Forte

The work of Atul Bose reflects a penchant for details. One can observe the influence of European realistic painting. He worked in oils, watercolors, and pastels, but preferred to use oil as the medium of his creativity. One of the sketches that gained him popularity (and scholarship), that is, the one of Ashutosh Mukherjea beautifully captures his facial expressions and certain anatomical peculiarities. Bose also made portraits of varied freedom fighters and in a sense infused the somewhat elitist art of portraiture with a ‘common’ touch that would resonate with people at large.

His portraits reflect the sensitivity of the artist who is in command of the nuances of technique and emphasis on details.

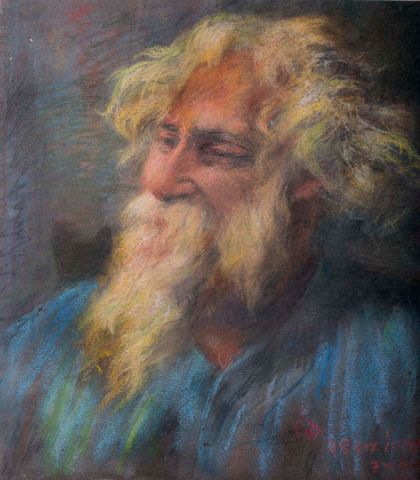

For example, the portrait of Rabindranath Tagore, which now hangs proudly at the Raj Bhavan Kolkata, is elegant and subtle, illuminating the radiant face and beard “painted in soft flesh tints standing out against the sable background,” [4]

His portrait of his wife, Devjani, is also considered to be a fine example of his work.

Since portraits painted by Bose often have famous people as subjects, one tends to overemphasize the portraiture. However, his other works are also distinct and highly coveted. These captured the essence of the times he lived in. Some examples include “Boats on the Padma” and a series of drawings on the Bengal Famine.

The drawings on the Bengal famine reflect a deep social concern that emerges very strongly. One can notice the technical finesse that is a part of his style. One also notices “ability to make shades of subdued colors to instill life into his subjects as well as their natural ambiance."(see 6).

Capturing fame

A Hundred Years Late (Rabindranath Tagore) by Atul Bose, 1976

A Hundred Years Late (Rabindranath Tagore) by Atul Bose, 1976

Today, we have ‘celebrity photographers’ who are entrusted with the task of capturing the images of celebrities. Was Atul Bose akin to the same in his time? After all, his works include portraits of the whos-who of the times, as well as some high-profile commissions. The portrait of Rabindranath Tagore is displayed in the Governor's Study at Raj Bhavan, Kolkata. This work of art was restored in 2009 (see 10) The painting was gifted by Bose to Chakravarthi Rajagopalachari, the first governor of Bengal after the British left. Another portrait of Tagore is on display at a museum, The Hermitage, Leningrad (St.Petersburg). (see 7). An oil painting portrait of Swami Vivekanda hangs at the Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkatta, as does the portrait of Michael Madhusudan Datta.

His work is on display in the Indian Parliament House as well [9]. Some portraits installed there include those of Deshbandhu Chittaranjan Das, Raja Ram Mohan Roy, and Shri Surendra Nath Banerjee.

Looking at Bose today

When we look at the work of Atul Bose in the context of his times, we can see a highly skilled artist who was faithful to his technique. We also see an individual who took art beyond the studio and worked at revolutionizing art education at that time.

An article rightly says, “Atul Bose was a teacher who was not entirely understood and an artist with a series of irreversibly lost opportunities, forgotten hopes, and unmitigated frustrations.” [2]

Today, with the benefit of hindsight, we can look at the work of Atul Bose with new eyes, and appreciate why his work finds a place of honor in museums and government institutes. He may have immortalized many individuals in his portraits, but perhaps the time is now ripe to look more intensely at the face of the skilled hand behind the portrait!

REFERENCES

[1] The Indian Portrait - V: Colonial Influence on Raja Ravi Varma and his Contemporaries by Manan Relia

[2] Sritama Halder. Art News and Views. Atul Bose: A Short Evaluation. June 2012.

[3] Shodhganga. "The Constant Influence of Contemporary Art." Chapter 7.

[4] Soumitra Das. The Telegraph. "Brought back to life." Tuesday, 20 October 2020.

[5] A.K. Coomaraswamy. The Yearbook of Oriental Art and Culture. Reviews by Atul Bose, H. 1924-25. 162 pages.

[6] Samir Dasgupta. The Telegraph. Life and death. Tuesday, 20 October 2020.

[7] Shodhganga. Conclusion. 25 pages.

[8] Portraits installed in Central Hall, Parliament House.

[9] Restoration and Upkeep of Rajbhavan, Kolkata.

Accessed for understanding the background:

[I] INTRODUCTION TO MODERN INDIAN ART & ABSTRACTION IN THE PRE-INDEPENDENCE INDIAN PAINTING by Mohinder Kumar Mastana, Assistant Professor, Apeejay College of Art Jullundur, Research Scholar Desh Bhagat University Mandigobindgarh, Punjab published in CASIRJ Volume 8 Issue 10 [Year - 2017] ISSN 2319 – 9202

[II] Chatterjee, Ratnabali. “'The Original Jamini Roy': A Study in the Consumerism of Art.” Social Scientist, vol. 15, no. 1, 1987, pp. 3–18. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/3517398. Accessed 7 Aug. 2020.