Somnath Hore was not one to paint the blue of the skies, the glitter of the sands, or the green of the whispering trees. Instead, he captured the helpless tremble of a hand, the frail body struck by hunger, lying on the ground. In Somnath’s vision, it was the stark reality of human suffering that demanded attention.

Starving bodies strewn across the village streets, mothers hiding children in their skeletal embrace, empty faces with sunken eyes, and animals with jutting out bones and half-peeled skin. These were the devastating effects of the 1943 famine, World War 2, and the Japanese Bombings that ravaged Bengal. Somnath Hore was witness to the human drama with a skill to translate the human predicament into art. His paintings, sculptures, prints, and drawings revealed a torn and injured world depicting a kind of social realism. His subject matter drew attention to the life of people in Bengal; the helpless, deserted, and starved after the Japanese bombings and man-made famine he witnessed in his early life.

Somnath Hore, Untitled (Floods), Lithograph

Somnath Hore recalls his first ever experience with any form of art activity at the mere age of seven. It was a seaplane model which he saw with his father on the river Karnaphuli in Chittagong. The urge to reproduce it was irresistible, Hore said in his book called Wounds. And hence he used cardboard, scissors, bamboo strips, gum, a penknife, a needle, and a thread to assemble a seaplane model. Hore deviated from school textbooks and fostered a passion for drawing encouraged by his teacher Debendra Majumdar.He observed and drew studies of objects by copying pictures of tables, chairs, gates, and boxes. He also drew compositions with straight and curved lines. Hore received the highest marks in this subject in school and acquired his first set of watercolour paints as a gift from his uncle at the age of thirteen.

He continued to recreate everything that he saw from magazines and calendars. Be it portraits, still-lifes, landscapes, and more. Hore also attempted to draw a copy of a moonscape from the nationalist leader Chittaranjan Das’s book of poems.

Somnath Hore, Untitled (Temple Sketch), Pen and Ink on Paper

In 1940, Hore secured his I.Sc degree from Chattagram Government College in Bangladesh. Somnath Hore then went to City College in Calcutta to study and reproduced a scene from the Ajanta Caves in black and white from a pamphlet his hostel mate gave him. He made a full-size wall drawing with sauce powders and paper sticks in his room. This was also the beginning of his association with the then-banned Communist Party which shaped his artistic oeuvre. He would make neat and legible handwritten, ink, and brush posters that were put up at various points in the city. These posters resulted in a fusion of Hore’s artistic and political sensibilities.

Underground activities have their own attraction for the initiated youth. This was during the second world war. When Germany attacked Soviet Russia in 1941 suddenly the slogans changed. I was not very concerned with the political intricacies of such slogans. My handwriting was attractive; the comrades liked my posters; it was reward enough for me. [1]

Somnath Hore

However, he had to leave the course in Calcutta to head back to Chittagong after World War 2 forced evacuation. Towards the end of 1942, the Chittagong Port was threatened by bombardments of the Royal Japanese Air Force after which all civilians were forced to evacuate. Bombs were aimed at Somnath’s neighbouring village called Patia on December 20, 1942. Scenes of the ravaged village scattered with lifeless bodies, gaping wounds, blood and death were stuck in Somnath’s mind. Haunted by these images, Hore wanted to record the entire scene in all its gory, ghastliness and horror. Hore drew sketches to record his strong emotional response to the human predicament at that time. Cruelty and human suffering became his art’s prime focus from the very beginning. Yet, he was still to discover and explore his artistic language.

Somnath Hore, Untitled (Village Scene), Pen on Paper, 1981

In the same year, Hore came in contact with Chittaprosad Bhattacharya ( a self-taught artist from Midnapore) who was living in Chittagong then. The 1943 Bengal Famine awakened a sense of artistic duty and responsibility amongst artists to represent the life of the people suffering in rural Bengal. At that time Chittaprosad was already wielding his mighty brush to record the misery inflicted by the man-made famine. When in Chittagong, Bhattacharya would travel from one famine ravaged village to the other, one bare kitchen to the next to document scenes of desperate hunger, poverty and consequential death. And even though Hore was rather young and inexperienced at that time, he followed Chittaprosad’s footsteps and did visual reporting from Chittagong. "Chittaprosad took me virtually by the hand and guided and encouraged me to draw portraits of the hungry, sick, and dying people. Whenever he was in Chittagong, he gave me company. From morning till evening I used to accompany him on his rounds. He initiated me into directly sketching the people I saw on streets and hospitals. With my untrained hand, I toddled from page to page." recalled Somnath Hore. [2]

Somnath Hore, Untitled (Lying Man with Dog), Mixed Media on Paper, 1982

The earliest of Hore’s visual reports were three sketches published in Janayuddha, July 5, 1944. Hore's depiction of the agonised human form through emaciated heads, sunken eyes and skeletal faces were elements initially used while documenting the Bengal Famine but can be spotted throughout his artistic oeuvre. These sketches captured the plight of the hapless victims of the famine through line or anatomical drawings,and representational contours of the subjects portrayed.

The children, who would invariably be there in most of Somnath’s drawings, would have out of proportion malarious spleens; their heads would be enormous skulls with bony faces perched on rickety torsos. [3]

Pranab Ranjan Ray

Towards the end of 1944, the editor of Janayuddha, Somnath Lahiri asked Hore to move to Calcutta to work with his publication. For a brief time, Hore created political caricatures even though he believed he was not made out to be a cartoonist. However, since caricatures require one to exaggerate selective features of a motif; these were quite evident in Hore’s later works.

In 1945, Hore joined the Government College of Art & Craft in Calcutta with a strong desire to gain formal training and also study under artist Zainul Abedin. Somnath Hore was intrigued by Abedin’s Famine Series and was eventually tutored and mentored by him in college.

This was a turning point in my life. The way he taught us and talked to us was a treat for us first year students. His brush was free of partisanship, his empathy for the exploited was immense, and he was systematic to the cause. I became an enthusiastic student of his, intent on mastering the technique of drawing and painting.

Somnath Hore

When Hore was in his second year of college in 1946, a major peasant upheaval in Bengal called the Tebhaga Movement emerged. This agitation coincided with his coming of age as an artist. This movement was a protest by the sharecroppers against the exploitations of the jotedars in Bengal. In the winter of 1946, the Communist Party assigned Somnath Hore as the visual reporter of the agitation in North Bengal. As a young art student, Hore witnessed the massive mobilisation of peasants taking place in various villages, recording the widespread spirit of peasant consciousness and militant solidarity over 12 days. With his pen and notebook in hand, Hore wandered off to see children and grandfathers toiling away in the tobacco fields. Women wrapped from chest to knee were grazing their cows. They were not well-built people; they worked very hard for very little to eat.

Hore created a personal diary with sketches of the Tebhaga days as an atypical social documentation through the eyes of a devoted artist. These sketches evolved from rugged lines to more sculptured forms. However, Hore maintained that one was not to expect perfection from these sketches. His drawings stand apart from the Tebhaga works of his contemporaries Chittaprosad and Debabrata Mukhopadhyay. One observes an uncompromising truthful revelation of the Tebhaga experience; unveiling personalities through lines.

From these drawings emerged more visionary wood engravings in the 1950s defining the Tebhaga movement. The sharp contrast between black and white in these pictures elicit a certain glow while faces emerging from and defying the dark send across a message of hope. These are pictures of meetings in the night where Hore conveys an abundance of faith and awareness sweeping the villages he visited.

This is the face of the peasant arisen. They are all here; with their lathis and sickles they harvest the crops as well as resist the thugs. Peasants, I felicitate you. The red glow of the new sun shines on your faces. Your fields are darkly stained and with blood. You will never surrender the vast golden paddy fields that you have nurtured with drops of your own blood. This I have seen and felt, this is my conviction. [4]

Somnath Hore

Hore’s depiction of wounds draws from his Tebhaga experience; continuously evolving from his early sketches to a darker more refined version of the same; finally translating into deep gashes on white paper as gaping wounds inflicted by a sharp knife.

In 1948, Hore was a party functionary and artist for the Communist Party. He immersed himself in designing and writing party posters. This was also the time when he started doing linocuts. Hore was still studying at the Government College of Art & Craft when the Indian Government banned the Communist Party. Like several leading members of the party, Hore too went underground in early 1949 even though he had one and a half years left to complete his graduation. After coming out in 1950, Hore dedicated himself to painting, drawing, and printmaking hoping to earn a living. However, financial constraints forced Hore to stick to drawing on paper, engravings, cut cheap blocks or planks of wood or linoleum, and take prints on paper. This was when he turned to his Tebhaga drawings from 1946-47 and made wood engravings and wood-cuts

The year 1951 was a period of intense experimentation and research for Hore. He made his first pictorial linocut distinct from the posters in 1952. In 1953, Hore joined the Calcutta Corporation as a teacher and conducted free art classes for children on Saturdays. In 1954, he made his first multi-colour woodcut and his first black and white etching. In the same year, Atul Bose, who was the Principal of the Indian College of Art asked Hore to take a job at the teaching school for a meager fee. He was joined by Sarbari Roy Chowdhury, Sukanta Basu, and Arun Bose at the school. From then on Hore devoted his life to art activity. He decided to spend more time in the company of activists in the field of visual arts than with his erstwhile political comrades.

Socialism is the social consciousness earned by the exercise of one's innate cognition. Artistry on the other hand is the special ability that one is born with. Socialism may well encourage an artist to create works of art, but it can never make him an artist. [5]

Somnath Hore

1954 to 1957 were residual screams in response to the famine etched in his memory. His wood engravings, wood-cuts, and monochromatic etchings focus on the theme of suffering humanity with more emphasis on the essential. Hore no longer needed historical context to depict suffering but focused on the agonised human form with more linear representations depicting masses under the strain of emotion. He then made intaglio prints using contour lines and tonalities to capture light and shade. In 1957, Hore got his Fine Arts diploma from the Government College of Art that had earlier been interrupted.

In 1958, Hore left Calcutta to join the Art Department of Delhi Polytechnic as a lecturer in Graphic Arts. The following years were explorations in his newly adopted mediums and techniques of matrix making, colour application, and print taking. In 1960, he held a solo exhibition of his muli-colour etchings and joined the Society of Contemporary Artists. 1964 saw experimentation in colour intaglio and its ancillary techniques. Hore relentlessly expressed his pain through different mediums throughout his artistic career.

Hore decided to go back to Bengal in 1967 when the art market was not particularly thriving. At the time, Calcutta was going through a political and social upheaval and Hore was disturbed by the conflict. In 1969, he headed the Printmaking department at Kala Bhavan in Santiniketan. He also came under the influence of masters like Ramkinkar Baij and Benodebehari Mukherjee. The way of life, his proximity to nature in Santiniketan bode him well, and he lived there until his death.

With Hore’s white-on-white series named Wounds, the 1970s saw a level of minimalism and abstraction. Devoid of human depiction, the concept of wounds became the centre of his art. The wound is a portrayal of the physical, emotional, and mental trauma through deep gashes, lacerations and cuts inflicted on handmade paper by Hore himself. The white-on-white series lets one not just see, but feel with one’s fingertips the anatomy of the unhealing wound.

The famine of 1943, the communal riots of 1946, the devastations of war. All the wounds and the wounded I have seen are engraved on my consciousness. A scarred tree, a road gouged by a truck tyre, a man knifed for no rational reason. The burin mercilessly cuts the surface of a woodblock, acid ferociously attacks the zinc or copper plate, these exercises continue without any premeditated design. In the end, an icon of wounds emerges. This icon represents the hapless, deserted, starved, and tortured.

Somnath Hore

Wounds represent the theme of war, starvation, and human suffering. The prints were made from moulds on uncoloured paper pulps used to form paper. Hore has moulded the white paper to form wound-like gashes to show the effects of war.

Somnath Hore, Bangladesh War, 1972, Bronze

During the summer of 1974, Hore started playing with bits of wax in the company of senior sculpture students at Kala Bhavan. He created some unusual figures covered in wounds. He made sculptures by twisting and turning wax sheets, cutting them with hot blades, making marks resonating with the impression of his Wounds. These sculptures were recast in bronze, and Hore discovered a new medium for his art.

In 1975, the victory of Vietnam over America aroused a vision in Hore, one of an eternal mother holding her head high with her newborn child cradled against her shattered chest. He completed this bronze in over two and a half years, but unfortunately, it was stolen in 1977 never to be recovered. Disheartened, he stopped making bronzes for some time.

In Santiniketan, Hore was influenced by the works of artists like Rabindranath Tagore, Nandalal Bose, Benode Bihari. Here, he had endless opportunities to create art. He worked alongside great masters such as Benode Bihari, Ramkinkar, and Dinkar Kowshik. K.G. Subramanyan too was a great friend and guide.

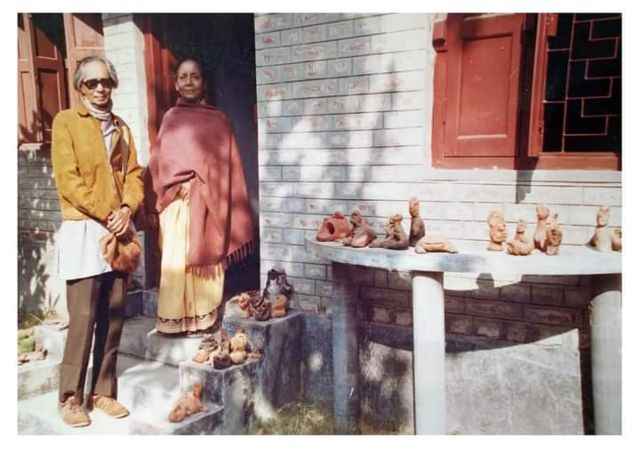

Somnath Hore and Reba Hore in Santiniketan

Somnath Hore and Reba Hore in Santiniketan

Picture Credits: www,banglalive.com

Somnath Hore retired in 1983 and built a modest house in Lalbandh, Santiniketan for Reba Hore (wife) and Chandana Hore (daughter). He rejected all worldly pleasures, building the house like a studio for his family of like-minded artists with a few beds here and there. Here he continued to pursue his bronzes- the same wounds, with bits of broken, twisted, moulded wax. Reba was busy with her paintings and terracottas. Chandana Hore had just finished her course at Kala Bhavan and was on her way to exploring her identity. The artistic couple continued to work in spite of the dimming of the eyes and the dwindling of the body, living out their creativity till their last breath.

Even in the last two decades of his life, Somnath Hore's grip on his paintbrush did not falter. A man who mastered various languages of artistic expression, Hore spoke against human suffering through strokes of resistance. In Hore's vision, it was the brush and not the pen that was mightier than the sword.

References

[1] Wounds by Somnath Hore, Readings: Somnath Hore, Lalit Kala Akademi

[2] Wounds by Somnath Hore, Readings: Somnath Hore, Lalit Kala Akademi

[3] Hunger & the Painter Somnath Hore & the Wounds, Pranab Ranjan Ray

[4] Tebhaga: An Artist's Diary and Sketchbook, Somnath Hore

[5] Partisan Aesthetics: Modern Art and India’s Long Decolonization.